Gabrielle “Gabby” Vázquez is a creative researcher born in Brooklyn to Puerto Rican and Dominican parents. She obtained her BFA in Fashion Design, in 2019, and an MA in Anthropology, in 2022, from Parsons: The New School. Her creative work derives from her interest in treating fashion as a medium for art, where she explores the concept of materiality and how it embodies memory. She examines how materials inhabit the body and influence its identity; in her creative process, she assembles, weaves, and unravels stories that shape her own sense of self, emphasizing the physical and emotional weight they carry. As a child from the Diaspora, her work reflects her journey towards cultural reclamation where she explores the complexities of Latinx culture and indigeneity, battling notions of erasure and displaying stories of resistance. She also focuses on matrilineal heritage, viewing women as a symbol of resistance and empowerment, while questioning the gender constructs imposed by colonizers in America and the Caribbean.

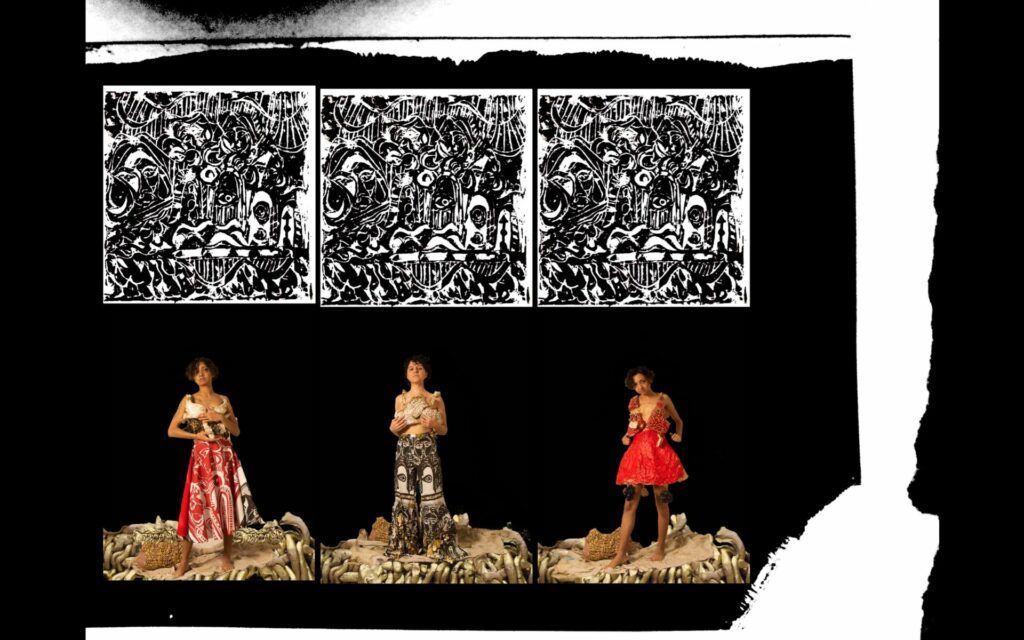

She began her journey towards cultural reclamation in 2019 with The Awakening of Diasporic Memory through Taíno Visual Culture, her thesis for her BFA. Prior to its conception, she traveled to Puerto Rico where she entered in dialogue with visual art from Taíno culture, the indigenous people who inhabited the Caribbean, including Puerto Rico, and was the group that made contact with European colonizers. She visited the Caguana Indigenous Ceremonial Park, a Taíno archaeological site in Utuado, and the Cabachuelas Studio led by Alice Chéveres—a ceramic workshop dedicated to revitalizing Taíno visual art by replicating archaeological objects and reimagining them (Babilonia, 2021). Here, she gained understanding of how Taíno people incorporated iconography as an important part of their language and culture. In this complex work of art, Vázquez employed fashion and photography to draw a focus on indigeneity and colonization by incorporating the female body as a spatial site for depicting narratives of erasure. Through her use of textiles and ceramics she embodies cultural oppression and gender constructs, while simultaneously arranging them to tell stories of resistance and permanence. The work consists of a digitally altered photograph that presents two scenes: a closeup image of a woven ceramic painted gold fashioned by the artist, and below a photographic rendition of a scene where two women sit on the floor to prepare a meal, while wearing garments created by Vázquez. The piece belongs to the photographic series CASSAVA (2019), a title that refers to a traditional bread made from manioc known as casabe, historically attributed as the primary source of food for Taínos. The importance of casabe in their diet translated into Taíno spirituality and religion, as the main deity known as Yocahú or “cassava/manioc giver” (Pané 1999). Additionally, given that cassava produced wellbeing and was deep-seated in their culture, the preparation of casabe is still present in various countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. Vázquez placed this ancestral ritual in a modern setting to challenge the notion that Taíno people are extinct. By doing so, she highlights the importance of casabe not only as a source of physical sustenance but also as a cultural, enduring sustenance with the potential of permanence.

Looking at the women in the scene, unaware they are being photographed, we become spectators of this ancestral ritual, like the European chroniclers that arrived during the colonization period in America. This photographic composition refers to the first images from the 16th century of American indigenous people, in which the nakedness of their body was emphasized and often sexualized, especially the women’s (Alegría, 1978). On the other hand, some of these first representations of American indigenous people were based on the iconography of Adam and Eve and the concept of Golden Age1, where nakedness was a symbol of innocence, free of sin (Alegría, 1978). Here, Vázquez presents their bodies occupied by clothes as a reference to these colonial narratives imposed onto Taínos; their naked bodies enclothed to highlight how their identity was forcefully manipulated by colonization and evangelization2. The women in the scene wear garments that function as a second skin through which their experiences materialize—serving as a way to carry history with them, with the garments embodying both colonial oppression and cultural resistance.

For the garments’ tops, Vázquez created ceramic breastplates for the women to wear that add a physical weight, a burden they are forced to carry. For one of the tops she weaves with clay, a motif found throughout her work which references indigeneity and visualizes the interlacing of stories. With these ceramic pieces the artist concentrates the weight on the area of the breasts and censors them. This way, she draws focus on femininity, embodying the gender constructs that plagued the Taíno people, which lived under a matrilineal system where family name and property was dictated by the mother’s lineage (University of Puerto Rico, 2006). The burden of these colonizer’s impositions materializes and weighs upon the chests of these women centuries later, impeding their preparation of casabe, a ritual essential for their survival.

In Little Details of Borikén, unseating disorder (2019), Vázquez approaches her work through a more personal aspect, not only because she includes herself as a subject, but also focuses on her own familial circle. Her journey toward her cultural reclamation shifts to focus on her close relatives from whom she learns about her familial and cultural history. For this project, Vázquez created garments based on the idea of fashion and how it relates to revolution, in the context of Puerto Rico and the Nuyorican diaspora. This photographic series documents the moment she met up with her grandmother, who she endearingly refers to as her Nana, to style the pieces for this project. For its production, Vázquez included both her Nana, who helped create some of the garments and her father, a professional photographer who captured the process of styling the pieces together.

The images, which took place at her Nana’s house, portray the intimacy of the process, as well as the collaboration it implies. The familiar space embraces them as they work to bring together this look that includes a blue strapless dress her Nana made, and a silk charmeuse top made by Vázquez. Her garments follow a similar style as those used in her BFA thesis pieces, with sketches painted in black over the white textile. Her iconography here alludes to the Puerto Rican Nationalist revolution, emphasizing Lolita Lebrón and her role in the fight for the island’s freedom. The idea for this project opened a dialogue with her Nana, a Puerto Rican from Morovis who poses as a direct link to the island and its cultural complexities, which allowed her to unpack and piece together narratives revolving around colonialism and resistance from a more recent perspective.

Beyond the theme of the confected garments, this work focuses primarily on the process of clothing creation, an idea alluded to with the pieces of scrap textiles superimposed on the scenes. Vázquez ties this idea of textile manipulation with the feminine figure, alluding to the historical tradition of weaving attributed to women, and consequently, emphasizes women’s role in the perdurance of culture. There is also a focus on the act of dressing someone else, as her Nana stands behind Vázquez and adjusts her dress, an intimate process that consists of a person manipulating another’s identity through clothes. This visual of her grandmother helping her fit these materials to her body to work as an alternative skin visualizes how identity is shaped by heritage. It is also an allusion to how colonial oppression and cultural dispossession is passed down from generation to generation.

The textile installation Material Convergence (2022) displays a distinct perspective of her artwork where the textiles stand on their own, devoid of a body. This installation incorporates textiles from Vázquez’s garments including earlier ones from 2017 and others from The Awakening of Diasporic Memory through Taíno Visual Culture and Little Details of Borikén, unseating disorder. The textiles used in this installation are mainly latex, a texture that remits the feeling of skin, which reflects upon the relationship between clothes and the body. Without this spatial site, the textiles become archival material, synthetizing her journey of cultural reclamation and self-discovery.

Through her creative work and her research, Gabrielle Vázquez captures the realities of living far from one’s land and the burdens this entails. She works with the enclothed body as a form of expression and presents how something as intimate as the human body can be violently manipulated to fit into certain constructs. Yet, with her creative work she proves how these narratives can be arranged to tell stories of resistance. Her art also presents her constant journey towards cultural reclamation, where she reconstructs and reanalyzes her work, building narratives from scraps all revolving around the idea that materials hold memories.

Footnotes

- Term used, in Christian context, to refer to a time before the original sin.

- Process of converting indigenous people to Christianity.

References

- Alegría, Ricardo E. Las Primeras Representaciones Gráficas Del Indio Americano, 1493-1523. San Juan: Centro de Estudios Avanzados de Puerto Rico y El Caribe, Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña, 1978.

- Babilonia, Jamilka. El taller Cabachuelas: La trayectoria hacia su fundación y la alfarería indígena en el presente. San Juan: Universidad de Puerto Rico, Recinto de Río Piedras, 2021.

- Culturas indígenas de Puerto Rico = indigenous cultures of Puerto Rico. San Juan: Museo de Historia, Antropología y Arte, Universidad de Puerto Rico, Recinto de Río Piedras, 2006.

- Pané, Fray Ramon, José Juan Arrom, and Susan C. Griswold. An account of the antiquities of the Indians: A new edition, with an introductory study, notes, and appendices by José Juan Arrom. Durham: Duke University Press, 1999.