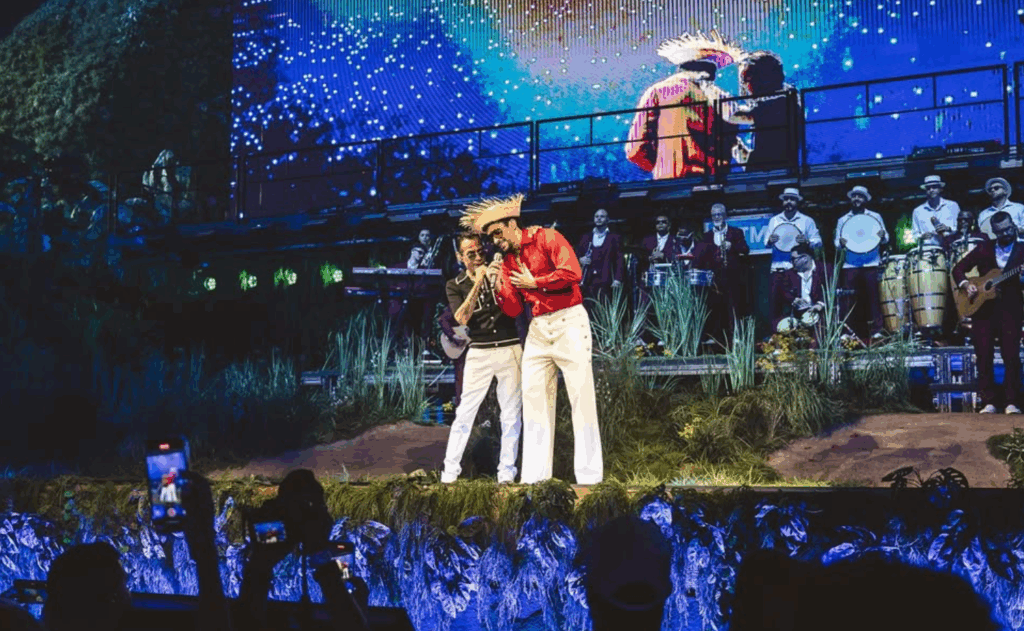

Sitting in my living room like so many other Puerto Ricans watching the live stream of Bad Bunny’s historic residency “No Me Quiero Ir de Aquí/ Una Más,” I immediately jump to my feet to grab my Puerto Rican flag (azul clarita, of course) when the familiar strums of “Preciosa” come on. As a DiaspoRican, unable to attend the show in Puerto Rico, Bad Bunny’s live stream allowed me to experience it live, and join the millions of other Puerto Ricans having watch parties in their marquesinas with their pavas on, and of course, que no falte el arroz con gandules, pernil y ron. As the concert navigates the emotional ups and downs of being human and living under the weight of empire through plena, salsa, and perreo, the performance of “Preciosa” captures the nuanced complexities of cultural identity from a diasporic perspective.

Marc Anthony and Bad Bunny’s performance highlights the multifaceted nature of “Preciosa” for the diaspora. Rafael Hernández composed the song while living outside Puerto Rico; Marc Anthony, born and raised in the diaspora, revives it for Puerto Ricans also watching from afar; and Bad Bunny brings it back to the archipelago in front of thousands at El Coliseo. In this moment, the song gathers together Puerto Ricans across geographies, giving voice to the grief of millions who have left yet still yearn to return. For centuries, Puerto Ricans have used music to record lived experiences, carry complex emotions, and contain their longings for home. This performance, for me, and I imagine for many others, was more than a celebration of Puerto Rico. It was the chance to sing, transgressing geographical borders, the iconic love letter that “Preciosa” has become for us.

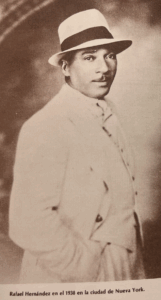

Hernández, Rafael. Fotografía. Colección Puertorriqueña, Biblioteca José M. Lázaro, Universidad de Puerto Rico, Recinto de Río Piedras. 2023

Marc Anthony’s cover and salsa renditions add to the bolero that was originally composed by Afro-Puerto Rican musician Rafael Hernández in 1937. Known as “el jíbarito nacional,” Rafael Hernández composed some of the most iconic Puerto Rican boleros, most notably “Lamento Borincano” and “Preciosa,” while living outside of Puerto Rico. These songs, which are so emblematic of Puerto Rican national identity, demonstrate both the commonality of destierro, which Yomaira Figueroa-Vasquez (2020) defines as an overlapping form of dispossession and displacement from homelands, and the nostalgic desire to return home. I read Hernández’s boleros as lamentations, a collective mourning of colonial wounds that have infiltrated our most intimate beings. I argue that “Preciosa” captures the lamentations of destierro: the complex emotions of forced migration, displacement, and dispossession that Puerto Ricans have endured since the first waves of colonization and enslavement in the 1500s, reverberating into the migrations we navigate today.

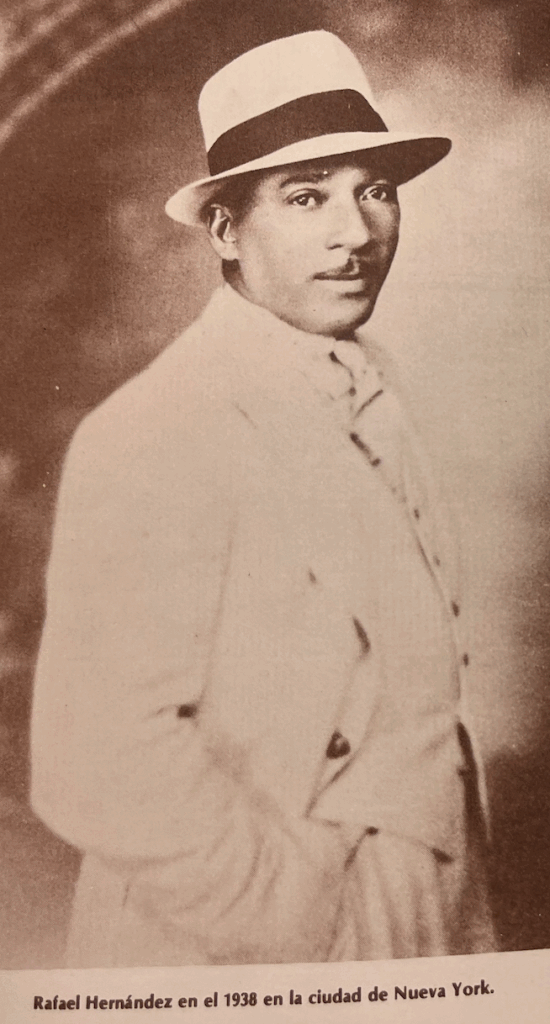

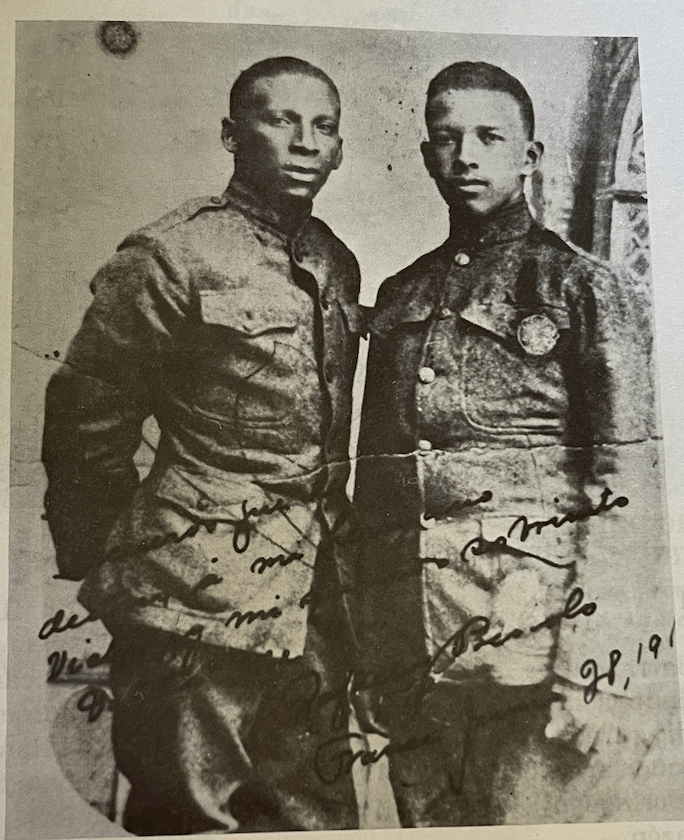

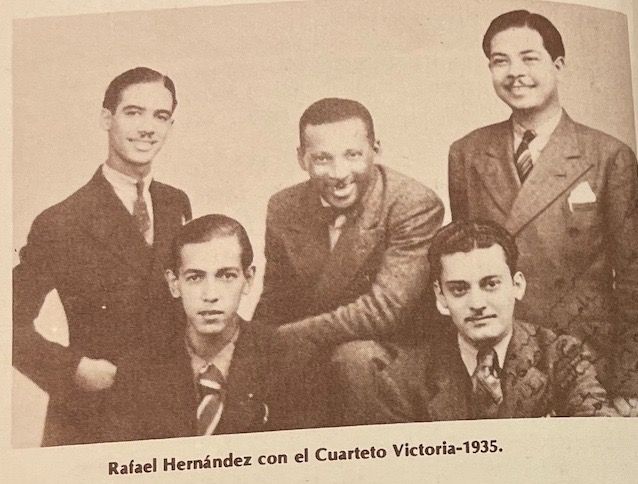

Born and raised in the coastal town of Aguadilla, Rafael Hernández worked the tobacco fields along with his family until his grandmother urged him to develop his musical career. Finding it difficult to get started, he enlisted in the army and became part of the Harlem Hell Fighters, through which he played alongside African Americans performing across Europe during World War I. He returned to New York in the mid-1920s and from there created his first musical group, which propelled him to fame. It was in New York, in 1929, that he composed “Lamento Borincano,” which José Luis González calls the first Latin American song of protest (Gonzalez 1985). Like so many Puerto Ricans, Hernández spent much of his life outside the archipelago, living in New York, Cuba, and Mexico, yet his music never stopped yearning for home. Living in Mexico for sixteen years, he composed “Preciosa” in 1937, another bolero that captures the nostalgic beauty of Puerto Rico, as he mentions the coastal beaches where he grew up, while also warning against the encroaching US empire that occupies Puerto Rico.

While some scholars, rightfully, have criticized the colonial nature of the song, as it elevates Spanish and Taíno inheritance while omitting our African inheritances, Hernández’s position as an Afro-Puerto Rican man adds another dimension to Preciosa: that of the inclusion of Afro-Puerto Ricans into the national imaginary. Whether he acknowledged it or not, his Blackness inevitably shaped the song’s meaning and reception. Still, it is crucial to recognize that Preciosa ultimately participates in the invisibilization of Afro-Puerto Ricans, particularly those descended from the transatlantic slave trade—the very system from which European and American empires built their fortunes. In this sense, Hernández’s symbolic inclusion does not entirely undo the exclusions embedded within the national narrative he helps construct. However, I argue that Hernández’s racial identity and his relationality with Black Americans in his musical formations disrupt the Hispanophilic nature of the song.

Hernández, Rafael. Fotografía. Colección Puertorriqueña, Biblioteca José M. Lázaro, Universidad de Puerto Rico, Recinto de Río Piedras. 2023

Hernández’s music became the soundtrack of the nationalist movement in the 1950s, serving as a collective anthem against the growing threat of US colonial endeavors, while also serving as a discursive tool to elevate a Hispanic Puerto Rico. While the song remained an archive of Puerto Rican resistance, “Preciosa” became an emblem of Puerto Rican music when Marc Anthony sang his rendition in 1999. Born Marco Antonio Muñiz to Puerto Rican parents in New York City, Marc Anthony grew up in East Harlem, where his father, a professional guitarist, would influence his trajectory into stardom. As a bilingual artist, producing music in both English and Spanish, Marc Anthony captures the diasporic experience that demonstrates being from both “aquí y allá.” He sings the cover of “Preciosa,” following the original composition of the song in 1937, when the song makes a sonic shift to salsa, and he adds the iconic lyrics that we sing nowadays. In this sonic shift, we also experience the diasporic element of salsa, a musical blending of Afro-diasporic sounds, born in relation to African American and Afro-Cuban rhythms, that originates in New York and travels across Latin America. Again, these subtleties, while perhaps unintentional, point to a legacy of Black and Afro-descendant culture in popular culture, and more importantly, in the formation of musical legacies like “Preciosa.”

The layers of diasporic experience imbued in “Preciosa” make it an important repertoire, to use Diana Taylor’s words, to the archive of Puerto Rican history. The song is born in the diaspora, and Anthony’s salsa rendition reimagines what it means to be Puerto Rican and who gets to claim Puerto Ricanness. As more and more Puerto Ricans get displaced by the failing infrastructures of colonialism in the archipelago, “Preciosa” is a reminder that one does not need to be born in Puerto Rico to claim it. As Anthony sings “por herencia de mis padres,” we have a claim to the lands where we have been displaced from, and that from any part of the world, we can sing the iconic lyrics. For Bad Bunny to include this song in a concert meant for Puerto Ricans living in the diaspora to sing alongside many other Puerto Ricans results in a unifying moment of resistance against US colonial logics.

Hernández, Rafael. Fotografía. Colección Puertorriqueña, Biblioteca José M. Lázaro, Universidad de Puerto Rico, Recinto de Río Piedras. 2023

“Preciosa” is a diasporic love letter to Puerto Rico–one that celebrates Puerto Rican resistance and identity, and maintains a commitment to celebrating what it means to be Puerto Rican regardless of where one is. Considering the diasporic nature of the song, it encapsulates the resistance efforts of Bad Bunny through his historic residency in El Coliseo. BadBunny’s “No me quiero ir de aquí” celebrates the desire for Puerto Ricans to stay and remain, against the growing threat of the U.S. empire that seeks to continuously displace Puerto Ricans, until we become minorities in our own land. Whilethe visibility of Blackness as part of the nation-building projects in Puerto Rico still remains in the margins, these subversive markers of Afro-disporic sounds across boleros, salsa, and, of course, regueatón remind us of the great continued cultural legacies Afro-Puerto Ricans have gifted us, and remain creating in the archipelago. That is the foundation of what it means to be Puerto Rican; we remember José Luis Gonzalez’s iconic essay “El país de cuatro pisos,” when he says that Afro-Antillian and Afro-Puerto Rican culture are the bases of cultural identity in Puerto Rico.

While much work remains in the process of what Rocio Zambrana theorizes as the unbinding or disentangling from colonial logics, Bad Bunny’s performance offers us a reprieve, a moment of unity across the worldwide Puerto Rican diaspora. The performance of “Preciosa” offers us a moment to connect with so many other Puerto Ricans and think about what it means to be both de aqui y de alla… What Bad Bunny’s livestream, hailed by Rolling Stone as the most-watched Amazon Music performance, reminds us of is the power of popular culture to bring us together through dancing and singing to Afro-Caribbean rhythms like perreo, plena, bomba, boleros, and salsa.

Flying my flag with so many other Puerto Ricans, singing in my living room “yo te quiero Puerto Rico/Yo te quiero Puerto Rico,” affirms my love for my nation and the fight towards liberation. That Puerto Rico, with all of its beauty, culture, y sazón, may one day see itself liberated from the tyranny of the United States, and that we may get to return to a Puerto Rico libre.

Marc Anthony (@marcanthony). 2025. Screenshot of Instagram post featuring performance of “Preciosa” at Bad Bunny’s concert “No Me Quiero Ir de Aquí” at Coliseo de Puerto Rico. Instagram. Posted 2025.

References

Figueroa-Vasquez, Yomaira C. Decolonizing Diasporas: Radical Mappings Figueroa-Vasquez, Yomaira C. Decolonizing Diasporas: Radical Mappings of Afro-Atlantic Literature. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2020.

Flores, Juan. From Bomba to Hip-Hop: Puerto Rican Culture and Latino Identity. New York: Columbia University Press, 2000.

González, José Luis. Puerto Rico: The Four-Storeyed Country and Other Essays. Translated by Gerald Guinness. Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener Publishers, 1993.

Zambrana, Rocío. Colonial Debts: The Case of Puerto Rico. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021.