I first met Christina in 2018. We were Innovative Cultural Advocacy Fellows at the Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute (CCCADI) in New York. Immersed in regular critical dialogue, our cohort was motivated by questions of space making given the realities of the city’s historic patterns of cultural divestment. We confronted ourselves and each other on our individual and collective responsibilities in studying, engaging, and representing Puerto Rican culture. As a researcher grounded in anthropological practice and occupied in/with the island’s material and pasts in existing institutional archives, I find contemporary art a productive disruption to normative approaches of locating history in any fixed setting with the potential of any singular dominant, interpretative stance. Delgado’s project reminds me of the possibility of narrative intimacy and a continual remaking of meaning in archival recovery work.

All at once heavily narrated and yet still ambiguous, archives arguably stand at the liminal intersection between physical site and cultural construct. They have been employed through academic scholarship and professional practice to constitute not only tangible sites of analysis as physical (and increasingly digital) data repositories but also reflect more abstract disciplinary conceptions around credible evidentiary sources and ongoing asymmetrical power relations given difficult histories of colonial abstraction (Manoff 2004). Through Delgado’s museological display of personal heirlooms in her family home, Tola’s Room might be perhaps better likened though to a form of Caribbean women’s life-writing that has been powerfully articulated as “a quest to understand both their own and their family’s absence from the historical record and why writing that absence is politically necessary to tell untold stories” (Fenton Stitt 2021, 4). The project of archiving in the Caribbean context in this way, offers a generative space to name and trace “processes that both constrain and open up the range of futures that are possible at any given moment” (Thomas 2013, 42). For Delgado, artistic practice is as bound up in creative production and public display as it is in collective gathering and collaborative learning.

What follows are excerpts of our dialogue around the personal motivations, documentary content, and new directions of the Tola’s Room project. In our culminating individual presentations as CCCADI fellows six years ago, we were asked to begin to formulate how we would center equity and inclusion in our personal practices as scholars and as artists. Delgado’s clarity of vision then of what I understood given my museum anthropological training as not your typical house museum has well materialized in the interim years from a position paper to a recognized site of Diasporican art and community in the city of Baltimore.

Amanda Guzmán: Collector origin stories are many and varied in my research experience. What motivated your interest in archiving and the creation of this public project?

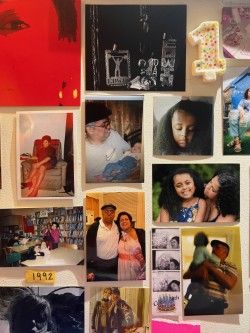

Christina Delgado: Tola’s Room is deeply rooted in my personal and family histories. After the sudden loss of my father in 2013, an interest in reconnecting to my cultural roots through family archiving inspired the creation of Tola’s Room, named after my daughter, Omotola. What began as a personal project evolved into a larger community space celebrating Puerto Rican culture and history, directly challenging Baltimore’s entrenched power structures that have historically marginalized communities of color. Motivated by my experiences in community work, where I witnessed gatekeeping and cultural invisibility, I created Tola’s Room as an act of counter-narrative to mainstream spaces of representation. The project which began as a celebration of my identity developed into sharing and valuing a broader narrative of Puerto Rican culture in Baltimore without waiting for formal permission or validation.

AG: In recent years, there has been a lot of discussion in the international museum field around defining the museum institution in a manner that might accurately represent the complex global realities of cultural heritage management and exhibition. From your perspective, how does the project parallel and depart from a “traditional” museum exhibit model?

CD: I redefine the seemingly disparate concepts of “home” and “museum” through Tola’s Room by creating an intimate space where personal and cultural histories are preserved and shared. In Tola’s Room, “home” moves beyond a singular site of origin or presence, becoming a space of extended communal belonging where cultural memory is actively maintained and celebrated through collective gathering and material activation. I reimagine the “museum” as a living, interactive space that invites participation, reflection, and connection, rather than just serving as a physical repository for artifacts.

Following some of the attributes of a “traditional” museum model in regards to structured forms of engagement, Tola’s Room can also be experienced by visitors through self-guided and guided tour options. As a result of a recent partnership with students from the UMBC CoLab, the space can also be engaged remotely with a virtual visit.

AG: Moving to the objects, let’s engage in some material close-looking. Could you walk us through the process of locating and curating materials for public display with some specific examples of object groupings and their relationships to spaces in the home?

CD: Many of the objects I started with in this project were personal belongings of my father, my mother, and my personal collection. Through different iterations of this project’s public display and the development of my artistic practice, I have striven to be intentional about materializing the concept of “home” to create meaningful relationships between the objects that I gather and the spaces in which they are positioned for exhibition. For example, “The Shrine,” part of my 2021 Relics of My Father exhibition, honored my father, Edwin Delgado, in a spiritually charged space with personal belongings atop a reflective altar. In 2022, my second exhibition, A Series of Love Letters, transformed my daughter’s former bedroom into “Daddy’s Den,” remixing my father’s belongings including vinyl records, clothes, books, family photos, and images of the “Relics of My Father series,” with a short self-produced film, “Daddy, A Love Letter.” The film projected family videos and my reflections since his passing onto a photo of the final Bacardi bottle that he drank. In my work, I invite visitors to directly enter and physically handle the spaces and objects of my life, suspending personal memory in material display.

AG: Your project is based in Baltimore, Maryland. I’m reminded here both of recent census data demonstrating major population growth in states like Louisiana, New Mexico, and Colorado as well as of examples of recent scholarship aimed at documenting migrant experiences beyond that of New York (García-Colón 2020; Lauria Santiago and Berg 2025). Given this context, why is it important for you to represent the Puerto Rican diaspora experience in the Baltimore community? What might such an artistic grounding contribute to building larger understandings of stateside diaspora?

CD: Through Tola’s Room, I directly challenge the entrenched power structures in Baltimore, a city with a long history of racial division and selective cultural invisibility, embodied in a selective representation of cultural identity, where certain aspects are deliberately omitted or overlooked. Baltimore’s history of redlining, I argue, has had lasting consequences for the cultural sector and resulting institutional patterns of representation.

I created Tola’s Room to elevate Puerto Rican culture in the city and provide a platform for cultural expression. My project not only addresses the lack of visibility for Puerto Ricans but also critiques the broader systems that exclude diverse cultural groups from the city’s official narrative and artistic landscape.

I hope that my work helps to establish more inclusive visions of the Puerto Rican stateside diaspora beyond that of more well known and historically documented sites, for example, cities like New York and Chicago. That said, “home” in a diasporic context can never be restricted to one physical location. My own personal journey, in fact, was an upbringing in New York with a long-term, ongoing relocation to/in Baltimore.

AG: Memory and home are key, interconnected themes in your work—first home as a personal site to remember your father and then home as a collective site to remember as a Puerto Rican diaspora community. How has the project changed since its inception?

CD: Tola’s Room began as a deeply personal project for me, inspired by my experiences as an artist, educator, and community organizer in a moment of profound grief. Initially envisioned in my home’s basement, it grew into a wider urban cultural initiative honoring Puerto Rican heritage across multiple discursive formats through interactive art, storytelling practice, and community events. The project also now supports and promotes artistic expression by larger creative communities of makers, for example, through varied themed workshops on mediums such as cyanotypes, printmaking and collaging.

Over time, Tola’s Room spatially expanded from a small, personal exhibit to eventually encompass my entire home, becoming a platform for celebrating and preserving the Puerto Rican diaspora’s cultural identity in Baltimore. My work now includes multiple, intersecting initiatives like the #BmoreBoricuas Project, which documents and shares the history of the Puerto Rican experience in Baltimore into the present, through archival research, oral histories, public workshops, acquiring local Puerto Rican artwork and artifacts, and an upcoming documentary.

References

- Fenton Stitt, Jocelyn. 2021. Introduction: Archival dreams and Caribbean life writing, 1–18. In Dreams of Archives Unfolded: Absence and Caribbean Life Writing. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Press.

- García-Colón, Ismael. 2020. Colonial Migrants at the Heart of Empire: Puerto Rican Workers on US Farms. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Hernández, Yasmín. 2005. Painting Liberation: 1998 and Its Pivotal Role in the Formation of a New Boricua Political Art Movement. CENTRO: Journal of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies 17 (2): 113–133.

- Lauria Santiago, Aldo A. and Ulla D. Berg. 2025. Latinas/os in New Jersey: Histories, Communities and Cultures. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Manoff, Marlene. 2004. Theories of the Archive from Across the Disciplines. Portal: Libraries and the Academy 4 (1): 9–26. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Thomas, Deborah A. 2013. Caribbean Studies, Archive Building, and the Problem of Violence. Small Axe 17 (2): 27– 42.

- Vagnone, Franklin D. 2015. Anarchist’s Guide to Historic House Museums. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.