As I am sitting near the pool table of one of Rio Piedras’s oldest bars, El Boricua, the hubbub from the players dancing and shooting pool stirring in the background, something catches my attention. Right underneath that table is an intricate pattern of tiles, hidden in plain sight as it were, mostly imperceptible to the patrons coming and going. After years of frequenting this bar, the fact I had just noticed its existence was testament to its ubiquity, or perhaps I just had not been looking hard enough. Precisely that familiarity and connection between lived spaces and invisible patterns is what I have found at the heart of much of Nora Maité Nieves’s work. One can notice the artists’ interest in the significance of materials, specifically the recurrence of shapes alluding to ornamental concrete blocks and losas criollas. hydraulic tiles with mosaic patterns. It is from this vantage point that I want to approach her work.

In the interest of clarifying our subject matter, I believe it necessary to briefly review the history of the objects from which Nieves draws inspiration. The documentation of the history of the ornamental block and the mosaic tile in Puerto Rico is an ongoing subject of study: the materials fabricated with Portland cement, both the ornamental block and the hydraulic mosaic tile, arrived at the island towards the end of the 19th century and their usage became widespread during the beginnings of the 20th due to an abundance of factors, principally their ease of distribution, accessible costs and resistance to the elements and vermin, but also in part due to the economic conditions of the Caribbean in the aftermath of the Spanish-American War (Del Cueto 2015, 6–7). All these elements positioned the ornamental block and the mosaic tile as tailor made building materials for the Hispanic Caribbean, this in turn explaining that common familiarity many of us Caribbean residents experience when seeing them1. These are objects that remind us of buildings from our past and that connect us with the cultures that have preceded us. The abundance of mosaic tiles in the design of buildings in Puerto Rico is also related to the islands political situation following the invasion by the United States at the turn of the century. Influenced by the abstract ornamental patterns of Islamic art, mosaic tiles were often used as a form of cultural reaffirmation in Puerto Rican architecture (Hernandez 2007, 45, 48). Taking all this into consideration, I believe that Nora Maité Nieves’s designs are then directly, or indirectly, tapping into various currents of thought and representation related to our past and present.

Of course, the recurrence of these forms is only one aspect of the artist’s work, but it is undoubtedly an important one. In her 2019 interview with Margaux Ogden, the artist herself clues one in on the meaning and importance of these shapes in her work:

The shape is from decorative concrete blocks that are really common in Puerto Rico, but I’ve also found them in NYC, especially Brooklyn and Queens. I love finding them in New York because it feels like finding a little bit of home inserted here. It is a joyous image for me, so I started using this part of it. It is like a leaf shape, but it is also like an eye and like a vagina. A very feminine shape. Sometimes I think of them as a representation of people. There was a big protest in Puerto Rico happening while I started working on one of the paintings, and an image came to mind of these shapes together in the room. It made me think of people marching, and it felt so deep and concrete that I went for it. (Nora Maité Nieves 2019, para. 17)

These leaf shaped forms, with their aleph-like nature, contain a multitude of meanings directly related to the artist’s identity. In this sense, I would like to single out the fact that Nieves has found these objects in New York as well because it exemplifies her use of them as a connection between the island and the diaspora. I am sure that the artist is not the only person living away from the island who has felt a little piece of home present in these otherwise inconspicuous pieces of architecture. One can look at the work of fellow SAIC alumni Edra Soto with her large, patterned structures, or the paintings of Brooklyn-based Marisol Ruiz as well, for reproductions and abstractions of these same shapes and materials. These works also suggest a connection, present in Nieves’ work as well, with the language of Puerto Rican vernacular architecture which, as mentioned before, served as a sort of method for cultural assertion. These materials are present in spaces transited by middle- and lower-class Puerto Ricans; there is a very strong connection here with memory and the people that identify seeing these shapes, whether they have seen them on the floor of an old bar or at their grandmother’s house ever since they have any recollection. The fact that the artist populates her works with these shapes, which can be understood as surrogates or stand-ins for human beings, once again reminds us of the importance of observing with purpose, the spaces that the artist presents are never devoid of people; on the contrary, it seems that Nieves is constantly reminding us of that idiom: aquí vive gente.

The connection that the artist establishes between the shape language of ornamental “breeze blocks” and the female body also strikes me as noteworthy, this inviting us to consider a sense of ever-present femininity embedded in the structures that we inhabit (and have been living in for decades). In this sense, one could consider this “embedded” femininity as positing an opposite or antithesis to the conception of the building as a phallic symbol following Freud, the notion of house or home being traditionally linked to maternity, which can be further problematized as well. In any case, this close symbolic relationship between the contiguity of forms, be they ornamental shapes in blocks, vaginas, almonds, leaves, eyes, all seem to remit to nature in one way or another, all of these aspects coalescing visibly in the artist’s work.

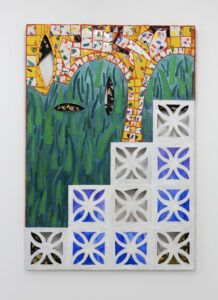

Specifically, I would like to revise how these aspects converge in the artist’s piece from 2019 titled Looking at My Neighbor’s Yard. In this piece, the artist employs multiple perspectives as she invites the spectator to peek through this metaphorical window into someone else’s lived spaces. This slightly voyeuristic aspect is heightened by the perforation of the canvas. The spectator looks through the breeze block all the way to the other side of the wall, effectively “trespassing” the veil between the artwork and the gallery space itself. This material quality that, like much of Nieves’s work, blurs the line between painting and sculpture, achieves this feeling using these familiar shapes in an ironic way; one of the original purposes of these ornamental concrete blocks was to decoratively provide homes with ventilation without sacrificing privacy. The mosaic tile patterns are also present in this work, forming a species of arch that also opens up allowing us a glimpse beyond the canvas. It becomes easier to understand the multiple perspectives that the artist uses when observing how these mosaics connect with the blocks below, suggesting a look at a floor that does not follow a logical representational sequence of space as we look down and forward all at once, at the same time evoking the shape of a structure that has been enveloped in tile patterning, reminiscent of places such as the old Colmado Carvajal pub in Carolina or the mosaic wall that adorns the entrance to La Pared, one of Luquillo’s most famous beaches. In this way, Nieves forms connections with spaces that we can recognize partially, perhaps because, in the same way that her paintings combine varying materials and methods, the spaces she presents are “collages” of varying memories.

Finally, one last aspect that ties into the symbolic connections between the patterns and nature is the yard itself, the greenery connecting the two elements previously discussed and once again allowing a look through the canvas itself. It is worth noting that this transgressive approach to the canvas and the blurring of boundaries between sculpture and painting could engage in conversation with the avant-garde art produced in the first half of the 20th century, thinking specifically of Argentina with Lucio Fontana, Gyula Kosice and other members of the Arte Madí movement. Following those concerns, it is evident that the act of looking is at the center of every part of this piece, the spectator looks at the yard from varying perspectives that all converge on one another, whilst at the same time looking through the almond-shapes into the background beyond and it is here that we can notice most easily the black and gold shapes hidden in a second plane. One can consider here the wide gamut of possible avenues that the artist might be suggesting with its inclusion, the combination of abstract patterns mimicking mosaics and the black and gold color scheme could be a nod towards divinity employing the methodology of Islamic art, and in this space we could consider, as well, the relation between the breeze block shapes and the female body, perhaps alluding towards the divine feminine, something not uncommon in the artists’ body of work.

Ultimately, the work of Nora Maité Nieves is in constant conversation with the spectator that engages with it. The artist asks for our patience and understanding in this process of looking from different points of view, to take notice of what lies quietly waiting around us every day, in the places we live in, in the spaces we form connections with other human beings. Just by slowing down and taking a minute to look closely, we could begin to see our surroundings, perhaps even our memories, in new ways. Nieves’s work asks for us to wait and observe closely and deeply at that which we might not understand from the outset, reminding us that there is always something new to learn, one only needs to know (from) where to look.

Footnotes

- It is worth clarifying that del Cueto and other authors point out, whilst ornamental blocks and mosaic tiles were brought over to the Caribbean by Spain, it was the United States’ economic interests in the region, particularly in Puerto Rico, that led in part to their widespread adoption in construction.

References

- Del Cueto, Beatriz. 2015. Moldes y prefabricados en el trópico caribeño: los mosaicos hidráulicos y los bloques de concreto. Archivos de Arquitectura Antillana, Revista Internacional de Arquitectura y Cultura en el Gran Caribe 56: 20—27. Academia.edu. Accessed 6 May 2025. https://www.academia.edu/30891291/Moldes_and_Prefabricados_en_el_Tr%C3%B3pico_Caribe%C3%B1o_pdf.

- Hernández Miranda, Zuleika. 2007. Curriculum vitae del mosaico hidráulico: orígenes de la losa criolla. Revista Conserva Conversa 3: 40—53. Accessed 6 May 2025. https://docs.pr.gov/files/OECH/Publicaciones%20y%20Recursos/Revista%20Conserva%20Conversa/Revista%20Conserva%20Conversa%20Vol%20III.pdf.

- Nora Maité Nieves, interview by Margaux Ogden, We Are More: Nora Maité Nieves Interviewed, BOMB Magazine, November 20, 2019. Accessed 6 May 2025. https://bombmagazine.org/articles/2019/11/20/we-are-more-nora-mait%C3%A9-nieves-interviewed/.