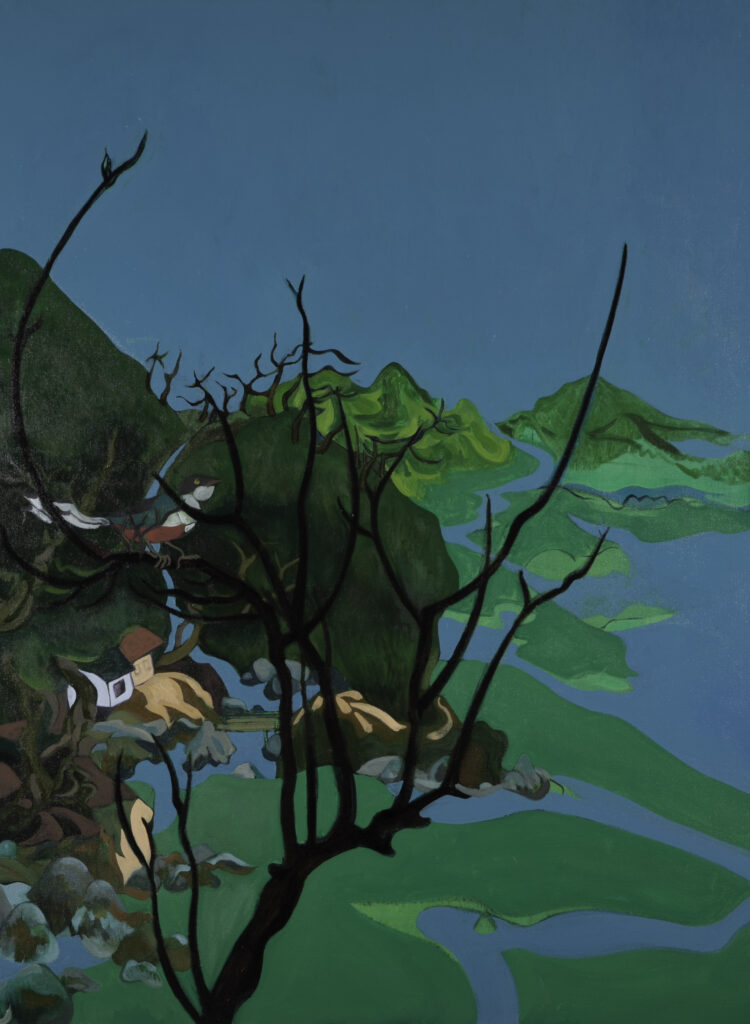

Miguel Trelles Hernández grew up on a diet of comic books, novels, and films. That sense of fantasy comes through in his painting Tocororo (2018). This piece, like many of Miguel Trelles Hernández’ work, combines elements from the Caribbean with Chinese dynastic painting. The result is a vibrant canvas where the artist gives a demonstration of his profound love of draftsmanship.

Trelles was born and grew up in San Juan, Puerto Rico. After completing a BA in Art History at Brown University, he began a Masters in East Asian Studies at Yale University before moving to New York City in 1992. He settled in the Lower East Side and went on to pursue an MFA at Hunter College under Juan Sánchez’ tutelage. His artwork, especially his prints, pay homage to the Lower East Side and the Nuyorican scene. Since 2001 he has explored an unusual combination between Chinese painting, American visual culture, Mesoamerican references, and Latin American and Caribbean culture. The artist explains it as follows:

A Caribbean provenance has heightened my awareness of the dichotomies between the art and culture of the four Americas: pre-Columbian, Colonial, and contemporary South and North America. Some claim the art of the West might be exhausted. Perhaps it is so. And yet Asian art, specifically the rich history of painting in dynastic China, is already proving a remarkably deep wellspring of inspiration for artists the world over. Chino Latino aims to draw from this well, generally disavowed by Western cultural hegemony over half a millennium. (Trelles)

In short, his art skews towards his personal world, and holds within it a preoccupation with difference.

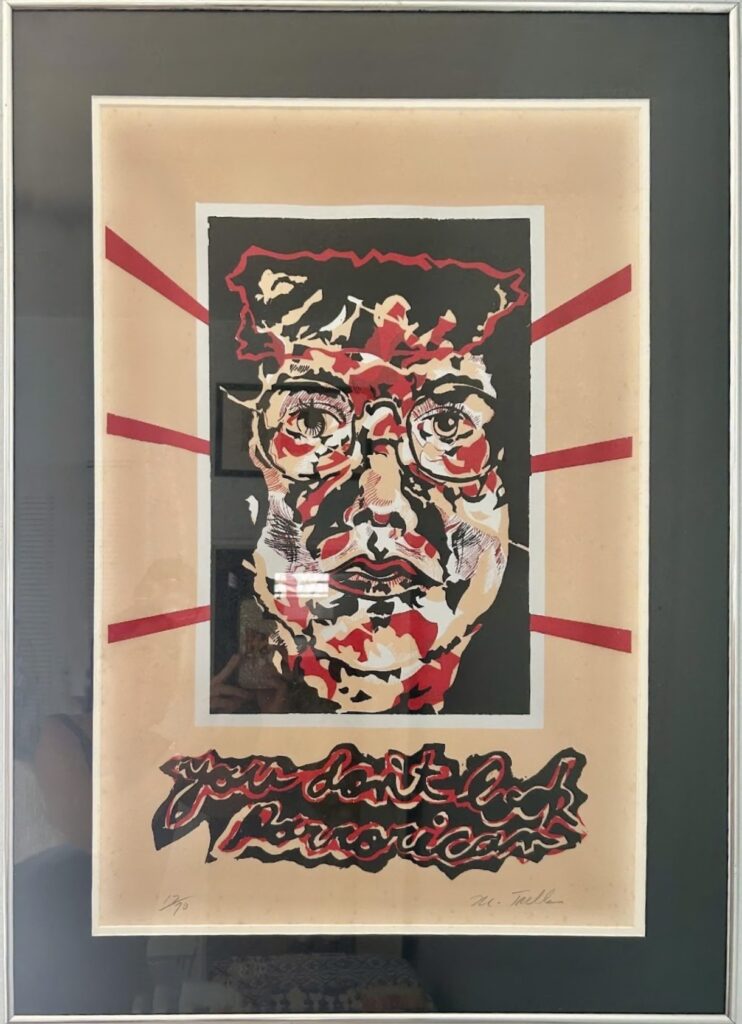

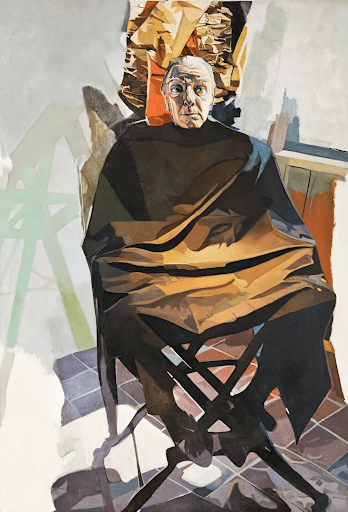

Early in his artistic development, while still an undergraduate at Brown University, Trelles produced a silkscreen entitled “You don’t look porrorican”(1989). An enlarged portrait of his bespectacled face, rendered in red and black, with the phrase emblazoned at its bottom, it is a testament to his early confrontation with prejudice. Later, he would turn that prejudice on its head when he posed Nuyorican poet Pedro Pietri in the exact manner that Puerto Rican painter Francisco Rodón posed Argentinean literary giant Jorge Luis Borges. With this appropriation, Trelles signaled the exclusion of generations of Nuyorican writers from the Puerto Rican literary canon. What does a literary giant look like, the painter seems to ask?

Óleo sobre lienzo. Image courtesy of the artist.

Tocororo is an excellent example of Miguel’s work. It represents a verdant landscape on a turquoise background. A bare tree in the foreground acts as a repoussoir. The tree dramatizes a sense of deep space that is not always easy to grasp, as hills, sea and sky seem to meld in a surface at once flat and mobile, liquid. Perhaps more importantly, the tree calls attention to Trelles’s line, creating a network of thick black marks on the painting’s surface. Perched on a branch on the left side of the painting and against a darker shade of green, a bird rendered in red, white, and blue can be distinguished. This bird is the tocororo, a distant relation of the quetzal’s of Mesoamerica and Cuba’s national bird.

It is a surprising development that this turns out to be the painting’s “raison d’etre”. Yet it also makes perfect sense, as Cuba looms large in this artist’s biography. The son of Cuban exile, Luis Trelles Plazaola, a distinguished professor and film critic, Miguel grew up hearing stories of Cuba’s past greatness. By choosing to reference Cuba through the national bird, whose colors coincide with those of the Puerto Rican flag as well – red, white, and blue – Trelles avoids confronting myths, or politics. Instead, the bird is placed in a landscape that is at once familiar and exotic. The artist captures a sense of divergence. Elements of the picture seem familiar – the intense blues and greens that are characteristic of paradisiacal representations of our islands – yet many more are unusual to the point of striking a fantastical note, such as the lack of depth or the vaguely ominous tree.

Space is an important part of this painting. The canvas both suggests great depth and flatness, and plays between such disparate references as Pop art, and Chinese scroll paintings. It is difficult to find parallels to this kind of work: Trelles does not use the usual tropes that would make it possible to compare this artwork to such color-rich renditions of Pop Art as Tom Wesselmann, James Rosenquist, David Hockney or R.B. Kitaj. Instead, his subject matter is filled with “revolutionary anarchism” remitting us to a world of personal references. One such reference is the tocororo bird. Another is the dynastic Chinese painting he so admires. In this case the reference is to a painting attributed to Yen Tz’u-yü (active between ca 1164-81) titled Hermitage by a Pine Covered Bluff, a small fan painting of ink on silk. As in this tradition, the space represented here is idealized and highly stylized. As in the dynastic tradition, Trelles’ work relies on the brushstroke as both a line and an area of light and shadow. Finally, as in ancient Chinese landscapes, the “empty” spaces, the margins are the areas where a sense of deep space is created, but rather than misty and aerial as in Chinese landscapes, here they seem both solid (flat) and liquid, creating a sense of movement as they butt against the vibrant green mountains. Why haven’t I written about this artist’s work before? I have certainly followed it and admired it my whole life. He is an extraordinary colorist, as Tocororo clearly demonstrates. He is deeply entwined with the Puerto Rico- New York art scene through his work as director of La Tea theater and the founder of Bori-Mix, a collective show that has run since 2006 at the Clemente Sóto Vélez Center. Perhaps it is because I am his sister, and it seems unprofessional. Or because his art is so unusual, so driven by his own compass that it is sometimes hard to equate with the existing image of Puerto Rican art. But the idea that the art of Puerto Rico and its Diaspora needs to look a certain way is as prejudiced as the observation that confronted him years ago and that led to the You don’t look Puerto Rican silkscreen. What does Puerto Rican art look like, after all?