In an increasingly militarized world marked by ever escalating colonial contradictions, apathy and hyper-individualism have become the plat du jour in the Global North. Enter Gisela Colón– a Puerto Rican artist living in Los Angeles, whose work pushes us to be in communion with the earthly, the cosmic, and the metaphysical. Colón has pioneered a language of Organic Minimalism, through which she employs a wide variety of disciplines–among them astronomy, archaeology, and geology, to name a few–in tandem with materials that speak to the ancient world as much as they do to the contemporary age. By appropriating materials that are often used to engage in surveillance and otherwise oppress colonized people across the globe–such as carbon fiber and optical materials–to speak of light, ancestral wisdom, and healing through our connection with the rest of the natural world. Colón’s work reminds us of the interconnectedness of our material existence—the carbon that forms the missile, the bullet, the body, and the earth all originates from the same source.

Colón possesses a background in economics and law, yet her thirst for creation began in her early years in Puerto Rico, painting extensively with her mother. Her work has been exhibited around the world, including Desert X AlUla (Saudi Arabia, 2020), Forever is Now (Egypt, 2021), XV Havana Biennial (Cuba, 2024), among numerous others. Her studio practice is currently based in Los Angeles and Palm Springs, California, as well as in Puerto Rico.

What follows is an interview conducted through written and verbal exchanges with Colón about her life, work, and the variety of experiences that have shaped her art.

What are the roles of color and iridescence in your work? Would you say each one of your sculptures has its own life force?

The color of my works comes from light (not paint) which is termed “structural color.” I developed a process of creating vessels that reflect and refract light into its constituent parts through layered structures. My sculptures incorporate many layers of optical materials folded into one another, much in the same way as the layers of my own stratified diasporic existence as a Puerto Rican artist living in the US. The immediate visual experience is one of a fluid color spectrum that prompts viewers to question what they are seeing. The sculptures create conditions of “impossible” colors because the rays of light are fragmented into indeterminate perceptual phenomena. Both the form and the colors constantly shift depending on the quality of environmental lighting and the movement of the viewer, generating structural color, which is also found in nature.

My use of light, color, and form is mutable – I create work with “humanized geometries,” a language of organic bodies that is constantly transforming its physical qualities to connect the viewer to the experience of Life itself. My works reference a larger universe of forms and matter that draw from both earthly and cosmic concerns. They contain their own life force.

In recent years, there has been a noticeable shift towards prioritizing environmental sustainability in art in terms of materials, longevity, and subject matter. What is your personal philosophy regarding the materiality of your work?

I believe in true material transformation where magic happens before your eyes. Something that is rudimentary or pedestrian can get transformed into a conductor of the invisible and metaphysical. For example, let’s take the subject of plastics, which in general, have become vilified. As a broad category, in the 20th century, plastics actually changed human lives for the better, creating broad advances in medicine, biotechnology, transportation, architecture, construction, design, engineering, etc. The impact was massively positive. The material itself thus, was not inherently bad, rather it was the disposal of single-use plastics that has contributed to the negative environmental problems we face today. When I use acrylic materials, I am actually up-cycling them and retiring them from potential adverse disposal, generating a positive use for them that enhances human living. Coupled with optical materials, these works generate a radiance of light that replicates the feeling of the origin of life. So, the ability of these materials to become something else completely different that embodies life force is what I call “transcendent materiality” – a means to an end that is greater than the sum of its parts. I have been able to create vessels of “structural color” which are vehicles of perceptual experiences founded on the scientific principle of refraction of light into its constituent color parts.

In the realm of Land Art and Environmental work, for the past five years I have also employed carbon fiber in several monumental installations around the world, including three UNESCO World Heritage sites, such as The Future is Now for the Land Art Biennial, Desert X AlUla (Saudi Arabia, 2020), Forever is Now (Egypt, 2021) presenting a site-specific monument at the Pyramids of Giza, a UNESCO landmark dating back 4,500 years, Godheads – Idols in Times of Crisis in the Oude Warande Forest (Netherlands 2022), Reclaimed Stones: Foundations of Civilization, Past, Present, Future, 2023, at The Citadel of Cairo or Citadel of Salah al-Din, a medieval Islamic-era fortification in Cairo, Egypt, dating to the twelfth century, and Plasmático: El Cuarto Estado de Máteria, a large-scale environmental activation on the Monumental Axis of Brasília, at the Museu Nacional da República, in Brasília, Brazil (2024).

It has been very meaningful to act in concert with the Earth, not against it. Historically, land art from the 1960s usually involved male interventions that caused scars on the earth; slicing, digging, and changing the natural environment in an aggressive manner was de rigueur. My philosophy is to create work that treads lightly on the surface of the earth, that can activate deeper conversations about our need to be in harmony with greater forces of nature, and thinks in terms of deep time and space across millions and millions of years.

As a Puerto Rican woman that is part of the Diaspora, has migration impacted or influenced your work? If so, how?

Of course. Movement across the land, across countries, and places changes you, enriches your perspective, makes you see things much more complexly, and you realize that everything has layers. My life and my work are a palimpsest of multiple layers of experiences across time and place. For me, the key to migration has been to bring Puerto Rico with me wherever I go. Uno siempre lleva la tierra por dentro, y como dice Bad Bunny: “Puertorriqueños que llevan años fuera de Puerto Rico duermen en ese lugar pero viven en Puerto Rico.” (Puerto Ricans who have been away from Puerto Rico for years sleep where they are but live in Puerto Rico.) I often feel exactly like this, so even if I am physically located in another place in the world, my heart, my soul, are still on the island.

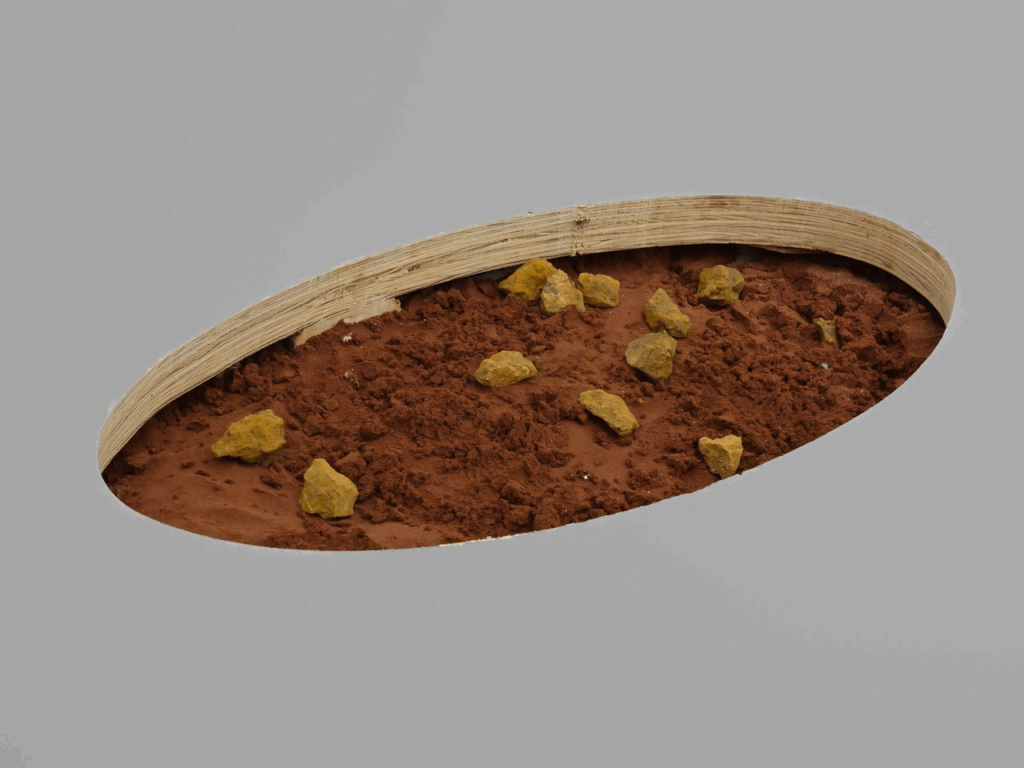

At times, I have incorporated actual earth matter from places of geographic significance to me, allowing my story to speak through the energy of this elemental matter. In a series of small-scale pigment “mountain paintings” titled Llevo la Tierra por dentro (Serie montañas de Puerto Rico) – (Los Picachos de Jayuya, El Yunque, La Cordillera Central, Las Piedras del Collado Cayey, El Cerro Maravilla) (2024), I explore identity through the metaphor of the orogenic mountain-building process. This process involves movements in the earth’s crust that lead to folding, faulting, volcanic activity, igneous intrusion, and metamorphism. The creation of majestic mountain forms serves as a symbol of strength and transformation. Each one of these works represents a mountain range in Puerto Rico that holds personal significance for me. These land formations embody my personal journey of becoming something convergent, blended, layered, irreversible, eroded, and transformed through migrations, cataclysms, gravity, and time. Two recent works, one of my 8-foot-tall monoliths titled Tierra de substrato Arecibo (Parabolic Monolith Hematite), 2022, as well as an architectural intervention De la Tierra nací y a la Tierra regresaré (Architectural Intervention / Excavation), 2024, incorporate red earth from land in Arecibo where my father was born, and is also the site of the Observatory of Arecibo where my early childhood fascination with outer space and the cosmos came alive. The distinctive ochre color of Puerto Rico’s red earth comes from the mineral hematite, an iron oxide formed over time. Hematite, one of the earliest pigments used by man, appears in ancient cave drawings throughout the world, as well as on other planetary bodies.

You’ve given specific names to your sculptural works (pods, rectanguloids, etc.) almost as if they were different characters, or species, from another world. Would you say your work composes a larger imaginarium?

Yes, I feel that I create new worlds that are inhabited by many different beings that are part of an interspecies of sorts. Each work feels alive to me and carries energy and information with it into the future. In a sense, they possess a life of their own. My practice often begins with the microscopic, focusing on the energy of life as manifested in the building blocks of nature–the vibrant energy of atomic particles, our intricate cellular composition, and the incredible torquing movement of our spiraling DNA. Then, I move to the macrocosmic, observing much larger universal geometries in motion.

Applying this conceptual framework to my practice, I often draw from deeply personal narratives and transform them into something that people can generally relate to in a more expansive way. The monolithic form achieves this on many levels. It begins with my own personal experiences with gun violence in Puerto Rico, then incorporates the collective Puerto Rican experiences of military colonialism on the island, such as the military occupation of Vieques and the use of our rainforests to test Agent Orange during the Vietnam War. Ultimately, it speaks more broadly to experiential intersections of Latin American colonial histories across the Caribbean and the Global South.

As a form, the monolith is first perceived as a bullet, projectile, missile or rocket. Yet, in the greater trajectory of human anthropological history, it has also been the form of amulets, artifacts, obelisks, among others. The monolithic form has manifested in the rudimentary runestones of Stonehenge, the conical mathematical magnificence of the Pyramids of Giza, and the sentient petroglyphs of my own Puerto Rican Taíno ceremonial stones of Caguana Park in Utuado. This singular totemic form has been used by humankind from the beginning of time as a harbinger of good fortune and, for apotropaic purposes, warding off evil spirits. In my practice, I utilize the monolithic structure to address age-old mystical questions, deep human fears and desires, and the perennial mysteries of our human existence. Where did we come from? Why are we here? Where are we going? What is the purpose of our existence? How can we exist in balance with the Earth again?

This interview has been edited for clarity and concision.