Islands arise through dynamic geological processes, including volcanic activity, tectonic plate shifts, and erosion. These forces not only create new land but also continually reshape the Earth’s surface. Over time, islands come to embody both fragility and resistance, existing in tension with the surrounding elements of nature. In his photographic series islotes, Kevin Quiles Bonilla uses the formation of islets as a metaphor for individual experiences—distinct yet deeply interconnected within a larger narrative, much like the structure of Puerto Rico’s archipelago. Comprised of the largest island and 143 smaller landforms, including Vieques, Culebra, and Mona, this geographic formation reflects the fragmented yet interconnected nature of memory. Through these visual fragments of personal and collective history, the artworks weave a cohesive exploration of identity, displacement, and belonging.

Much like islands, Puerto Rico’s history has been shaped by tumultuous pressures such as colonial exploitation, political upheavals, economic instability, and waves of migration, all of which have permeated its social fabric. Just as islands develop and evolve through constant movement and instability, Puerto Rico’s identity has been forged through cycles of disruption, revealing a fragile yet enduring foundation. Drawing from his personal experience as a Puerto Rican living in the diaspora, Kevin Quiles Bonilla’s work is deeply motivated by the socio-political realities of Puerto Rico and its diaspora. His practice emphasizes contemporary representations of colonialism, the fluid dynamics of unstable terrains, and the complex relationship between Puerto Rico and the United States. In this specific project, Quiles Bonilla delves into the fragmentation of family structures and the forced abandonment of one’s native land, shedding light on the profound impacts of colonialism and resettlement.

The act of migration, central to the series, is neither foreign nor unfamiliar to Puerto Ricans; it is deeply embedded in the archipelago’s history, shaped by constant cycles of movement. For centuries, migration has been a response to economic, political, and social forces, often driven by the need for survival and the search for better opportunities. The mid-20th century, for example, saw a significant wave of Puerto Rican migration to the United States, driven by economic hardship exacerbated by industrialization and the decline of agricultural sectors on the island. This period, known as the “Great Migration,” led to the relocation of hundreds of thousands of Puerto Ricans, seeking employment in urban centers in the U.S. mainland, particularly in New York and other northeastern cities. More recently, however, a confluence of factors has intensified this migration pattern, reshaping Puerto Rico’s physical and social landscape. Colonial laws, such as the imposition of the Jones Act in 1917, which granted U.S. citizenship to Puerto Ricans but also stripped them of significant political power, laid the groundwork for a long-standing tension between belonging and displacement. Coupled with political instability, economic challenges, and the aftermath of devastating natural disasters such as Hurricane Maria in 2017, the island’s sense of stability has been severely disrupted. Additionally, the rising cost of living, the persistent struggles with public debt, and the limited local job opportunities have created an increasingly untenable situation for many Puerto Rican families. This combination of factors have contributed to one of the largest exoduses of Puerto Rican families in modern history, surpassing even the peak years of the “Great Migration,” during which approximately 237,000 Puerto Ricans relocated between 1950 and 1954 (Duany 20)

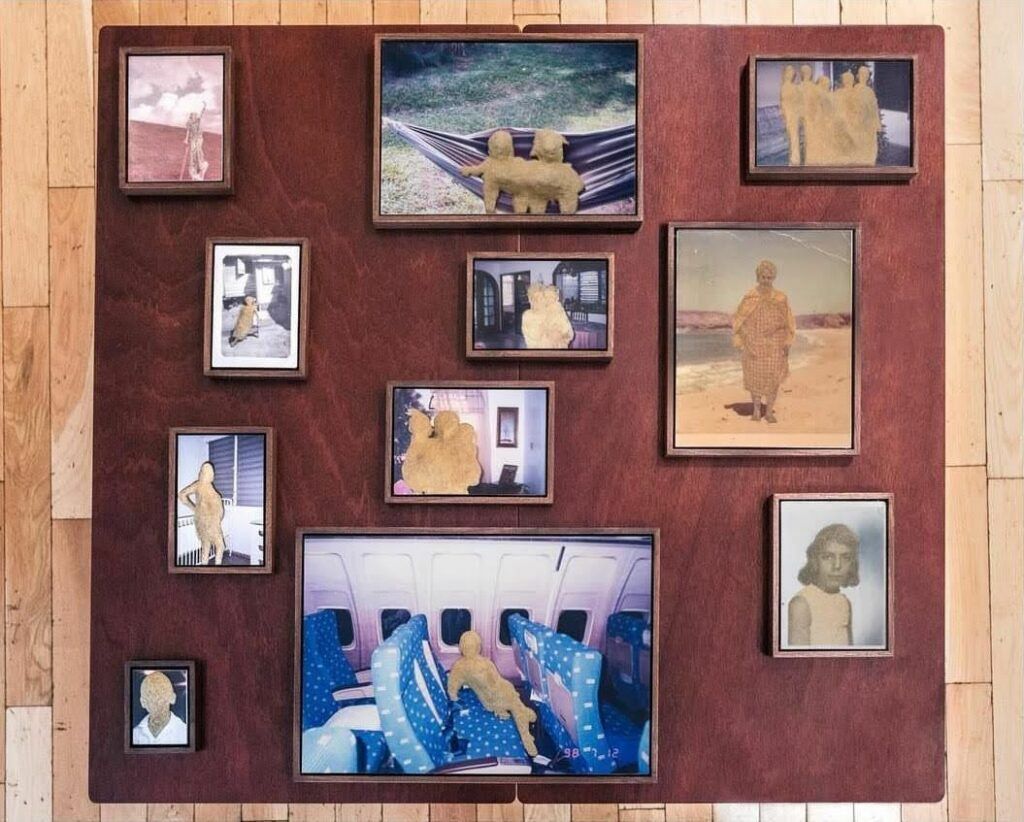

This ongoing displacement has left deep emotional and cultural scars, as families navigate the fragility of preserving collective memory while coping with the loss of proximity to their homeland and loved ones. The images in islotes respond to these challenges, capturing the physical and emotional distances that migration imposes and exploring the complex relationship between memory and belonging. Composed of chromogenic prints based on photographs from the artist’s family archive, these pieces capture significant moments in his family’s history. They unveil a personal narrative that spans from the artist’s childhood to moments predating his birth, offering a glimpse into the lives and memories of his family.

Quiles Bonilla intervenes in these images by covering the bodies and faces of his relatives with layers of sand. This aesthetic gesture juxtaposes memory and nostalgia with the disintegration of familial bonds, while also highlighting the fragility of the photographic medium itself. Just as photography incarnates specific moments in time, preserving visual details that evoke past experiences and emotions, Quiles Bonilla’s project emerged not as a formal artistic endeavor, but as a personal initiative to preserve his family albums. Concerned about the natural deterioration of the photographs, the artist digitized them, ensuring the memories they materialized would endure despite the passage of time and the separation imposed by distance.

Family albums are perhaps one of the first and most familiar ways we encounter photography. They hold an intimate and tangible record of time, weaving together images that tell stories of milestones, everyday moments, and bonds between generations. For many, these albums act as portals to our past, preserving cherished memories and forging connections with those who came before us, those who may no longer be with us, and places that no longer exist. When presented at Baxter St, these photographs were not displayed on the gallery walls but arranged on two tables, inviting viewers to engage with them as they might with their own albums in the intimacy and comfort of their homes with their families.

Through this approach, Quiles Bonilla’s work encourages viewers to reflect on their own familial legacies and the ways in which memory shapes identity. By engaging with his family’s photographic archive, the artist not only preserves memories but also reinterprets them to address broader themes such as colonialism and fragmented identities. His artistic interventions on these images, particularly through the addition of sand, transform personal relics into metaphoric landscapes. The photographs evolve into visual representations for the shared obstacles of Puerto Rican communities. This process of transformation challenges the traditional notion of memory as a fixed, static entity. Just as sand shifts and alters its form, Quiles Bonilla’s interventions remind us that memory, too, is subject to change and reinterpretation. His work emphasizes that the past is not merely a collection of immutable images but a dynamic force that continues to shape our understanding of the present and future.

Sand, as the central material of these interventions, symbolizes the passage of time and the ever-changing nature of life. Its application over the images evokes both healing and resistance to oblivion. Through this presentation, the artist invites us to reconsider the materiality of sand—not only as a fragile substance, but also as a robust foundation sustaining life. Despite being composed of rock particles and mineral grains, sand as a whole forms a solid structure that endures in the face of the vast sea. The title of Quiles Bonilla’s solo exhibition, A Small Patch of Sand Yet It Holds So Much / Un pequeño trozo de arena, pero aguanta mucho, where this series was first presented, emphasizes the profound symbolic and emotional weight of this natural element. Sand’s malleable nature allows it to adapt to its surroundings, responding to the movements of the human body, water, and wind. Additionally, the marks of human presence and natural history embedded in sand function as ephemeral records of time. Quiles Bonilla uses this organic material as a carrier of memory, transforming it into a repository for remnants of the past. This transformation underscores the significance of change—much like the formation of islands, which can both create new land and erode existing ones, altering borders and coastlines over time.

With the use of sand, Quiles Bonilla reconfigures his family’s images, creating islets and sand reliefs that turn the photographs into symbolic landscapes. The addition of this material evokes small dunes in the sea, symbolically uniting the different images/memories through a shared foundation beneath the surface. Islets—small portions of land surrounded by water—often symbolize isolation, a sentiment heightened by territorial disputes and physical borders. Yet, the sea that encircles these landforms also serves as a unifying force, connecting distant points on a common plane. Despite physical separations, shared experiences cultivate a collective identity and cultural history, bound by intangible connections that transcend what is visible.

Kevin Quiles Bonilla’s islotes poignantly confronts the complexities of migration and and identity in changing spaces, using the formation of islets as a powerful metaphor for connection. Through the addition of sand to his family photographs, Quiles Bonilla transforms this ephemeral material into a vessel for memory and time, bridging physical and emotional distances. The sand, fragile yet enduring, serves as both a marker of life’s impermanence and a testament to the enduring ties that bind individuals and communities. By reshaping personal memories into collective narratives, islotes bridges individual experiences with universal themes of belonging and loss. Quiles Bonilla reminds us that memory, like sand, is ever-changing, yet it holds the power to anchor identities and histories across generations. Through this intimate yet universal exploration, his work becomes a profound meditation on the fragility and strength of human connection, offering a testament to the enduring spirit of Puerto Rican identity amidst the shifting landscapes of time and migration.

References

- Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors. n.d. “Territorial and Jurisdiction Oral Health Programs: Puerto Rico.” ASTDD. https://www.astdd.org/territorial-and-jurisdiction-oral-health-programs-puerto-rico/

- Duany, Jorge. 2017. Ida y vuelta: Experiencias de la migración en el arte puertorriqueño contemporáneo.