Brenda Cruz Díaz is a woman of many hats. She is an interdisciplinary artist, (art) historian, and researcher. Cruz Díaz was born in San Juan, Puerto Rico in 1974, and resides in Madrid, Spain, since 1997. She completed her BA at the University of Puerto Rico in Río Piedras, and obtained her PhD from the Universidad Complutense de Madrid, in 2016. She is a printmaker and photographer. Her work deals with issues around gender, race, and national identity through a decolonial lens. She remains an active stakeholder in the transatlantic cultural production field, participating in large-scale events like Cumbre Afro at UPR, as well as exhibiting and collaborating with prestigious institutions like El Bastión in Old San Juan and Casa de América in Madrid.

The following is a translated and edited transcript of an interview with Doctor Cruz Díaz. She discusses her work and its relation to history, how she embeds meaning into it through the usage of materials, as well as the ways in which her life experiences inform her creative process.

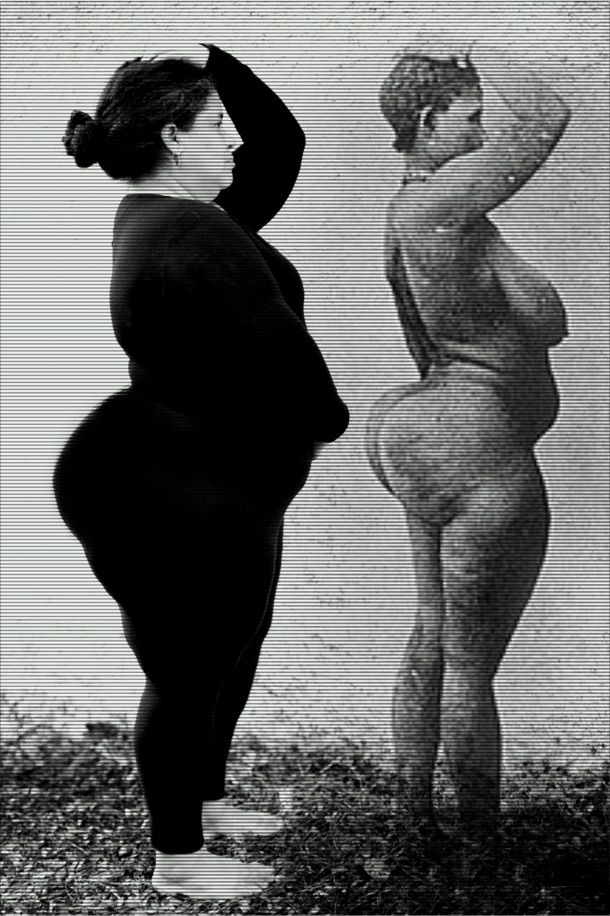

SBC: I understand your oeuvre to be deeply grounded in the history of photography. You employ photos with an ethnographic gaze (as in your piece La Venus de Hottentot), war photography (like in AlieNation), or even recur to the carte de visite,1 which was key in making photography more accessible. How do you reflect upon the relation of your photographic work and the history of the genre?

BCD: In the series you point to and previous ones like Retrato de una (de)colonizada, photography has been present as a medium to reflect upon the construction of a historical discourse. I consider it important for my work to have multiple readings, revealing the many layers of the concepts I tackle. You create relations and construct discourses and histories through a visual language. We continually transit from past to present, questioning and revisiting Western hegemonic written history. I resort to historical references and archival photography to create new histories and ways of knowing. Disdéri’s carte de visite was key in diversifying photography; but it, too, consolidated the roles of dominating classes and racial stratification. In this case, my photography is that of an Afrodescendant woman donning cultural and religious objects (that in the past were rarely shown in cartes de visite). History is my starting point to pose questions, in the hopes of rewriting it. From works like Árbol genealógico2 and Retrato de una (de)colonizada, I debate that hegemonic history has always favored the same few, silencing the subaltern.

SBC: You are a farmer, not only by virtue of having your own orchard, but also hailing from a lineage of farmers from Loíza and Río Grande.3 Agriculture is very present in your art. Tell us more about the importance of this theme in your work.

BCD: I always strive for my art pieces to reflect my life, for there to be a symbiosis between life and art. On the other hand, my work created after migrating to Spain has turned more self-referential. Ever since childhood, we’ve been connected to nature and agriculture. In our backyard we always grew plantains, avocados, lemons, guavas, acerolas. My father’s family are Afrodescendants from rural Río Grande and Loíza. My grandparents and great-grandparents worked with sugarcane, coffee, and other crops. I’ve been investigating my family’s past for years. Now in Madrid, living on the outskirts, we own land. We’ve been growing it for over fifteen years, with a focus on permaculture and seasonal harvests. So, it’s as much of a life experience as art. Moreover, my last artistic proposal, birthed as a product of Seminario Laboratorio Anti-futurismo Cimarrón, is a video installation and art happening, in which I present a video of rescued oral histories, from my father and my aunt, about their childhood and their own family histories, as well as culinary recipes and traditions of Afro-Puerto Ricans. With this work, besides denouncing the blanqueamiento of Puerto Rico, I want to honor the culture of this Afrodescendant region and my own ancestral heritage.

SBC: The significance of materials throughout art history is often neglected. The choice to print on PVC banners (as in the works featured by CentroPR) seems like a particular one. What factors make you gravitate toward that material?

BCD: Over time I have even questioned the use of PVC, which might be interpreted as anti-ecological; it’s plastic and it could go against my values. I’ve printed my last few works on cotton canvases. That came to be because in my artistic practice, the media exist to the service of the concepts. PVC canvas impressions make for an interesting contrast between black, white, and sepia tones, and allude to analogous photography. Current materials referencing old ones winks at the notions of past and present that are always at play in my work. I like the usage of industrial and street materials breaking away from the traditional frame or paper print of photography – or even art and museums in general.

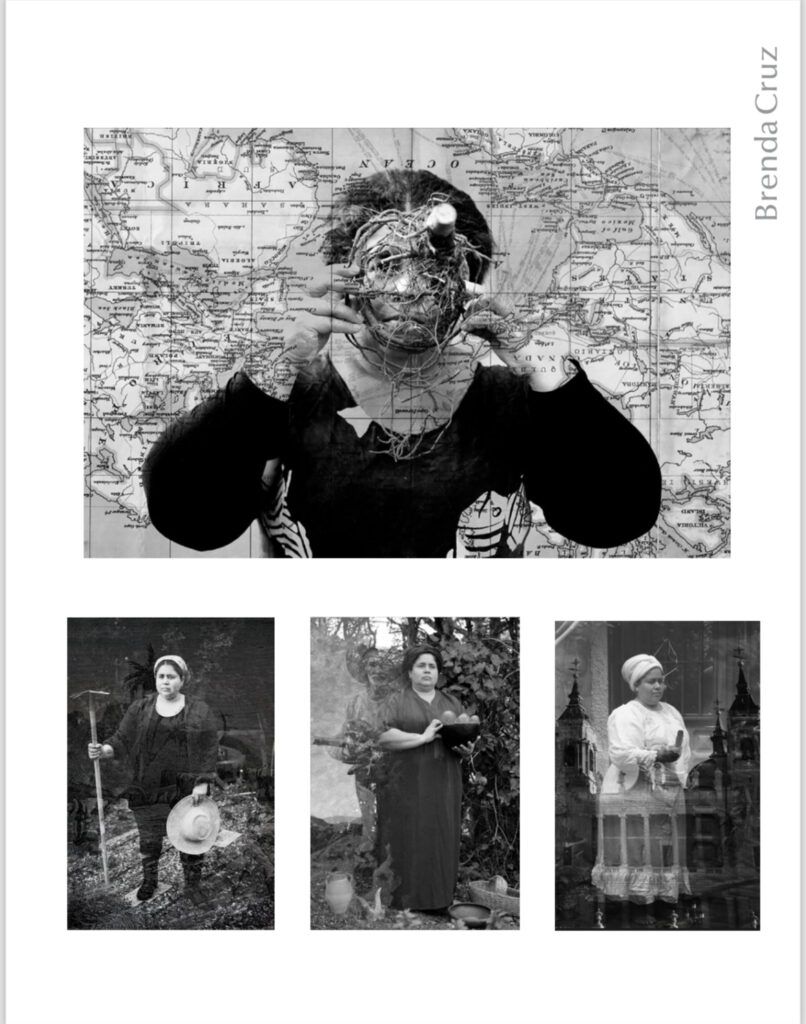

SBC: In your self-portraits we find the technique of superimposition, be it maps, old photographs, iconic artworks, or even immigration documents. In an interview with curator Mariel Quiñones Vélez you described this method as an “analogy” and your works as “containers of ideas and concepts.” In your opinion, what end do these visual games respond to?

BCD: Drawing analogies from images aids in understanding them better. I always relate the superimposition of images and elements to how you create an image in the graphic arts, the discipline I come from. My art background in college was printmaking. This way of creating and composing images is related. The juxtapositions in my pieces make matters of the past evident, pushing them into our present. The roles I assume in my self-portraits showcase my multicultural identity and reaffirm my blackness. These games make the spectator an active participant, prompting them to question and reformulate what they’re seeing.

SBC: Bravely, you put your body on the line when making art, especially considering the violences Black, female, and migrated bodies are subjected to. Have you felt scared making your body vulnerable to art publics?

BCD: That violence is precisely the rationale behind employing my body and my self-portraits. I haven’t felt fear; on the contrary, it’s been an exercise of healing and reaffirmation. I find my body and my self-portrait to be a powerful element. Ultimately, showing your body as an instrument of expression is the best way to narrate yourself and your problems. I will say, however, that on occasions I’ve considered nude art as the best way to vindicate and reflect what I have wanted to show. But in the end, I’ve censored myself and haven’t been able to show my body that way. I still have fears and shame over my body and obesity – which I hope to surpass in future works. This is applicable to my piece La Venus de Hottentot, as for the photo series Gula.4 Had I posed nude, they would’ve conveyed a more cogent message.

SBC: I’m fascinated by your piece América-Yo-Europa. Once again, we revisit agriculture thanks to the roots centered in the composition. You invert the Mercator projection of maps (reminiscent of the axioms behind América invertida5). The piece frames the Atlantic, with Africa & Europe on one side and the Americas on the other. It could very well be a poster image for the concept of globalization. Your body vanishes over the ocean, an ocean that was the channel for millions kidnapped out of Africa and forcibly taken to the Americas. The Atlantic represents a cemetery for so many of those people whose lives were taken in transit. Do you see this artwork inspired by your own immigrant experience, echoing the millions of migratory experiences that have constituted these so-called Americas?

BCD: This image does use Torres García as a starting point, and reflects upon his thesis: “nuestro norte es el sur.” In this map, he supports indigenous art against dominant influences. This direction shouldn’t be limited to the art world, though, but in a wider sense against US-American & European cultural hegemony. Maps have always reflected the dominant ideologies of the world. In a sense, it’s a recalibration of the South as an epicenter of movements. At the same time, I show my central self-portrait as if it were part of the map, another continent, and the plant before my head alludes to agriculture and my roots of origin, a metaphor for what nourishes us. I find myself between these two worlds, but always mindful of where my North is. There’s a myriad of histories deep below the currents of the Atlantic, and they certainly drag that colonial past, human trafficking, and continual exploitation of resources. It’s both about physical, but also, mental migration – about belonging to a larger whole. América-Yo-Europa speaks to those hybrid identities, mixed ones, arguing that we’re not from one single territory, but that we’re part of aworld, all with equal opportunity.

Footnotes

- Small photograph format patented by French photographer André Adolphe Eugène Disdéri in 1854.

- These were pieces created by Brenda Cruz Díaz in 1999 encapsulating found objects and historical prints inside polyester resin prisms.

- Loíza and Río Grande are coastal cities east of San Juan, PR.

- Gula (Spanish for gluttony) is a photographic series created by Cruz Díaz between 2015 and 2016. In these photographs, the artist poses in a kitchen and superimposes images of unappetizing foods around the compositions.

- Joaquín Torres García, 1943. This drawing by the Uruguayan artist and ideologue is an emblem of Latin American art and typifies the values of his indigenist “universalismo constructivo.”