Since color became the default in cinema, using black-and-white is now a deliberate choice (Misek, 2010). In black-and-white cinematography, lighting plays a crucial role in defining contrasts and visual dynamics. In Puerto Rico, cinema exist since it was brought to the archipelago’s shore at the end of the 19th century. All through the first half of the 20th century movies in Puerto Rico were produced and shown in black and white due to the technical limitations (Rosado 2023). To ensure it looks good cinematographers must expertly plan how the film will appear without color (Humphreys 2016). This meticulous planning is exemplified by Quintín Rivera Toro in his short films No (2021) and Mariló (2022).

In these two films, Quintín Rivera Toro employs monochromatic high-key cinematography not only as an aesthetic choice but as a powerful narrative tool that reveals the emotional complexities of his characters, exploring themes of empowerment within patriarchal structures and underscoring the psychological struggles faced by women in contemporary Puerto Rican society. In No, a bartender confronts her ex-boyfriend at work, leading to a tense confrontation. Mariló follows a mother and daughter as they confront an intrusive male figure.

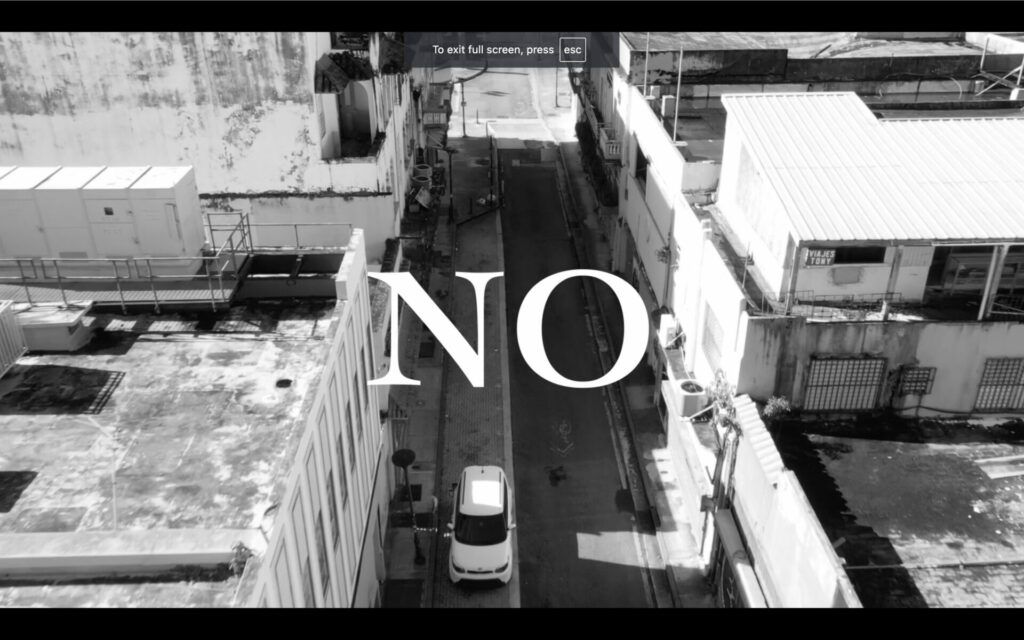

Rivera Toro begins these two films by showing the audience the spaces where the stories are confined. In Mariló, we see open spaces through wide shots directly lit by the sun. These spaces represent an urban, tropical Puerto Rico, somewhat worn down by scarcity, a harsh city where a palm tree sways in the wind, a rooster paces back and forth, stray dogs break the fourth wall and stare into the camera, garbage piles up in the frame, a man on a bicycle emerges from an alley with a Puerto Rican flag scorched by the blazing sun in the background, and a house with a dilapidated car seems abandoned. All these images create an impression of suffocation while being interspersed with shots of the daughter painting with what appears to be charcoal, a process that blackens her hands, nose, and feet. These shots are taken from a zenithal position in an over-the-shoulder view, as if someone is watching over her. This act could be interpreted in countless ways by the audience depending on the context in which the story unfolds in the film. In No, the film begins with an aerial shot of the city, and just as in Mariló, we see a city devastated by neglect, scorched by the sun, in a succession of wide shots that reveal the spaces where the story will unfold. Once both films introduce us to these spaces and take us inside them the decision to use medium shots and close-ups to isolate the characters becomes apparent. This approach, combined with high-key black-and-white cinematography and selective color schemes enhances character relationships, highlights key plot points, and guides the audience toward the artist’s intended message.

In both films, female characters are initially confined to spaces: the bartender to the bar in No, and the young girl to her room in Mariló. Both reflecting their emotional isolation.

In No, the bartender gazes at a couple nearby showing affection towards one another and the black-and-white scene shifts into bisexual lighting triggering a flashback in which the bartender argues with her ex-lover. In Mariló, the girl’s solitude is interrupted by her mother, uncomfortable with her lover’s behavior. Like the bartender in No, she daydreams, but instead of memories of conflict she imagines places and colorful paintings. One could argue that, within a socially and culturally patriarchal structure, both characters are not only isolated, but also chained to domestic tasks traditionally associated with the female gender. In the case of No, the bartender is drying glasses, much like a domestic worker or housewife might do, while the young girl is painting or engaging in crafts. When the cinematographic image shifts to color in No, Rivera Toro presents a scene where the bartender decides to break free from the yoke of a possibly abusive relationship based on a simple analysis of the images the artist presents. In the case of Mariló, the girl breaks free from the monotony of creating black-and-white images by envisioning more elaborate colorful paintings.

The use of color in both instances serves as a turning point for the female characters allowing them to break free from the constraints they face. In No the bartender is jolted out of her daydream when she sees her ex-partner walk into her workplace. In Mariló, the young girl loses focus after hearing her mother’s boyfriend persistently making advances towards her mother. The mother, protective of her daughter, asks the boyfriend to leave. When he resists the girl joins her mother in a united show of feminine power forcing him to go.

High-key lighting, known for its bright, minimal-shadow frames, typically creates a cheerful, lighthearted mood (Deguzman 2023). In Rivera Toro’s films high-key lighting is employed to establish tone, which, contrary to expectations, doesn’t necessarily evoke a joyful or cheerful atmosphere. Similar to Pawel Pogorzelski’s cinematography in Midsommar (2019) or John Alcott in The Shinning (1980), Rivera Toro’s films are brightly lit creating an unsettling ambiance. The sun plays a pivotal role in both films with both beginning under a harsh Puerto Rican sun that leaves no room for darkness. Instead, darkness is represented through the characters’ intentions. Their faces are often half-lit, always facing the sun or another light source creating shadowy contrasts. However, even in these contrasts complete darkness is never fully realized.

In No the stark lighting reflects the intense emotional tension between the bartender and her ex-lover making the bright open setting feel oppressive rather than cheerful. In the end, the bartender achieves complete liberation by punching her ex-lover, leaving the bar, making a visual statement in her ex-lover’s shop, and leaving the scene with an empathetic female driver who signals her approval of these actions as they both leave towards the brightness of the day. In Mariló, the bright airy lighting contrasts with the emotional weight of the mother-daughter relationship. The lighting emphasizes the psychological isolation of the characters as the young girl loses herself in her drawings suspended in the bright yet stifling atmosphere of her room. When the mother and daughter unite to confront the mother’s intrusive boyfriend, the high-key lighting emphasizes their empowerment contrasting with the emotional darkness of the situation.

In both films, Rivera Toro uses high-key lighting not only as an aesthetic choice but as a narrative tool that underscores the complexities of his characters. The brightness illuminates their vulnerability and emotional states, creating a dissonance between the visually light setting and the darker emotional undertones of the story. This juxtaposition allows the audience to feel the weight of the characters’ struggles, even as they exist in spaces filled with light. Monochrome further accentuates these struggles as the lack of color reflects their emotional vulnerability and detachment. The bartender and young girl’s disconnection from reality is underscored by this visual restraint highlighting their isolation and making their moments of empowerment resonate more deeply.

In visual storytelling, light and color are among some of the most powerful elements that allow viewers to reach an emotional level while their conscious minds interpret the story on another plane. Contrast defines depth, spatial relationships, and enhances both emotional impact and storytelling (Brown 2016). One tool often used in contemporary cinema is monochromatic schemes frequently to encode memory and the past. An example of this is Ray Figueroa’s Érase una vez en el Caribe (2023), a Puerto Rican film where despite being shot entirely in color, a monochromatic scheme is reserved for flashbacks that explore the past of the main character, Juan Encarnación. A similar example can be found in Pauli Cofresí’s Nos Persiguen (2022) where the black-and-white color scheme evokes a 1950s aesthetic reminiscent of the DIVEDCO films from that era. Contemporary films like C’mon C’mon (2021) use it to evoke nostalgia tied to family and childhood (Marzola 2022).

Alex Weintraub (2019) argues that contemporary black-and-white films share an aesthetic risk as the format is now used for style rather than necessity. The challenge is determining if its use serves the film’s content or is merely incidental. Many independent filmmakers use black-and-white for its gritty, documentary feel, helping low-budget films stand out in a color-dominated world. Cinematographers like the late Conrad Hall disapproved of color, finding it to be unreal and often distracting from the essence of the story (Kanfer, 2008). Rivera Toro’s work aligns with this perspective as his use of black-and-white minimizes distractions ensuring the focus remains on the emotional and narrative core of his films. Today, the choice to use black-and-white reflects the story being told, not technical limitations (Humphreys, 2016).

The use of a monochromatic color scheme is rare in contemporary Puerto Rican cinema where most feature films are shot digitally and in color. Over the last five years, Puerto Rican cinematographers have developed a distinctive style that is easily recognizable in modern films. This style often adheres to standard conventions that distinguish commercial films from more artistically daring ones such as the rule of thirds, intentional framing, the use of colors evoking tropicalism, and pronounced contrasts to define characters. This consistency can be attributed to the fact that a small group of cinematographers works on the majority of high budget Puerto Rican films.

On the contrary, the monochromatic scheme of Rivera Toro’s films heightens the emotional depth, reflecting the characters’ internal struggles and sense of isolation. The colorless visual style creates a sense of suspension mirroring the girl’s and the bartender’s disconnection from reality as they navigate their aspirations. The use of monochrome in Rivera Toro’s films accentuates the characters’ vulnerabilities making their moments of empowerment feel even more impactful. This sets them apart from the body of films released in the past five years.

As Rivera Toro employs high-key lighting within a monochromatic framework, the resulting contrasts between light and dark create a sense of tension that underlines the emotional stakes of the narratives. This technique not only highlights the characters’ internal conflicts, but also serves to elevate key moments of action and revelation reinforcing the thematic resonance of empowerment and liberation. This showcases the skill of a multidisciplinary plastic and visual artist like Quintín Rivera Toro.

References

- Brown, B. 2016. Cinematography Theory and Practice, 3rd ed. Routledge.

- Deguzman, K. 2023. What is High Key Lighting-Examples & Creative Uses. January 22, 2023. Studiobinder. https://www.studiobinder.com/blog/what-is-high-key-lighting-definition/.

- Humphreys, J. 2016. MONOCHROMATIC-BLACK AND WHITE FILM IN OUR MODERN ERA OF FILMMAKING. Cinerambles. https://cineramble.com/2016/09/monochromatic-black-and-white-film-in-our-modern-era-of-filmmaking/.

- Marzola, L. 2022. The History of Black-and-White Cinematography: From Its Death to Latest Oscar Trend With a monochromatic slate of Oscar contenders and a new version of “Nightmare Alley,” what does history tell us about this current trend? https://www.indiewire.com/features/general/history-black-and-white-cinematography-death-latest-oscar-trend-1234691108/.

- Misek, R. 2010. Chromatic Cinema: A History of Screen Color, First edition. Wiley-Blackwell. Rosado, E. 2023. El cine nuestro de cada día. Cinemovida.

- Weintraub, A. 2019. What’s Contemporary About the Academy Awards? Post45. February 24, 2019. https://post45.org/2019/02/the-black-and-white-art-film-in-the-age-of-its-digital-distribution/.