Gabrielle Vázquez is having a lot more fun than you or me. Equal parts artist and art, she has transcended this traditional dichotomy, liberated herself from old-hat archetypes such as the tortured sculptor, the depraved poet, and the prophetic painter. Vázquez is not driven by the everyday, but by the extraordinary—in her words, that which is “fabulous,” “juicy,” and “extravagant.” Her life is a testament to the core theme of her work: “embodiment.”

Vázquez shepherds me through the maximalist rooms of her family’s multigenerational Brooklyn brownstone. The walls boast an abundance of Dominican and Puerto Rican flags and the air is colored with the smell of freshly baked empanadas. Each room suggests that Vázquez carries with her a responsibility to honor her heritage. There is a clear sense of joy in her environment, and a heft of love. She is committed to reclaiming ancestral languages and identities, and she does so effortlessly, and in style. “I’m surrounded by a community of fabulous Latinx creators, mentors, and friends.” She boasts, “I don’t need a muse.”

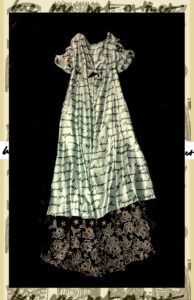

Visual Culture”, 2019. Mixed Media (digital print depicting printmaking,

ceramics, and dress), Print size varies. Image courtesy of Gabrielle Vázquez.

Over the last decade and a half, I’ve witnessed Vázquez’s complex evolution as an artist. Born into a family of artists, she began in illustration and painting, and has since come into her own as a multimedia artist with a focus on fashion, or wearable art. Her work incorporates ceramic pieces that mimic Taíno ceremonial objects, blends organic ribbons of paint with scripted words from Spanish and indigenous languages, and shines in the color gold—“Gold,” Vázquez reminds me, “is a symbol of Latin America’s colonial legacy.” She mixes materials as diverse as ink, beads, silk charmeuse, wire, digital prints of her illustrations, liquid rubber—“and lots of grommets,” Vázquez emphasizes.

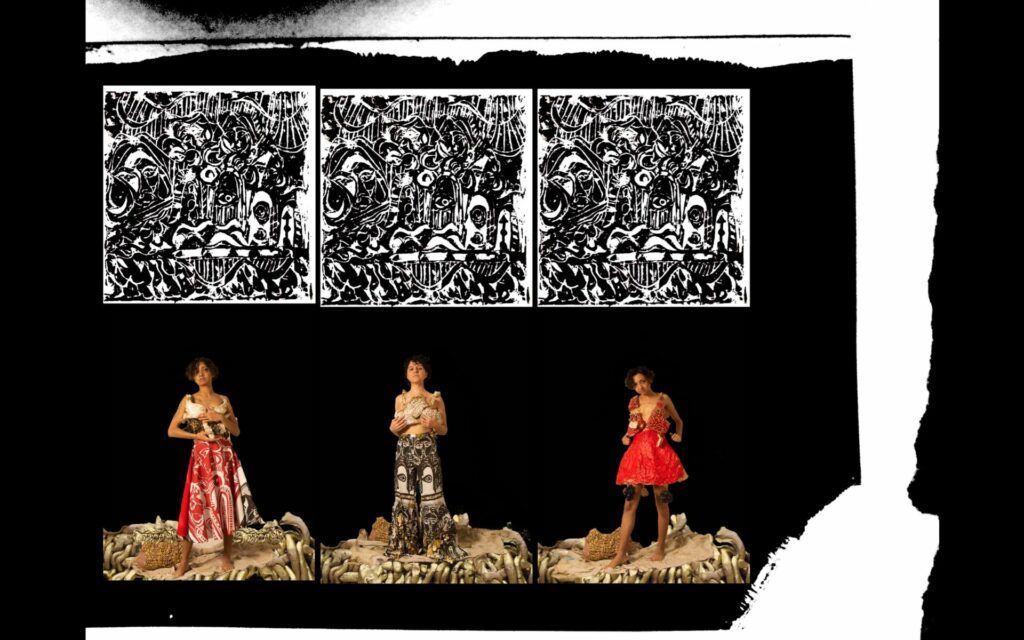

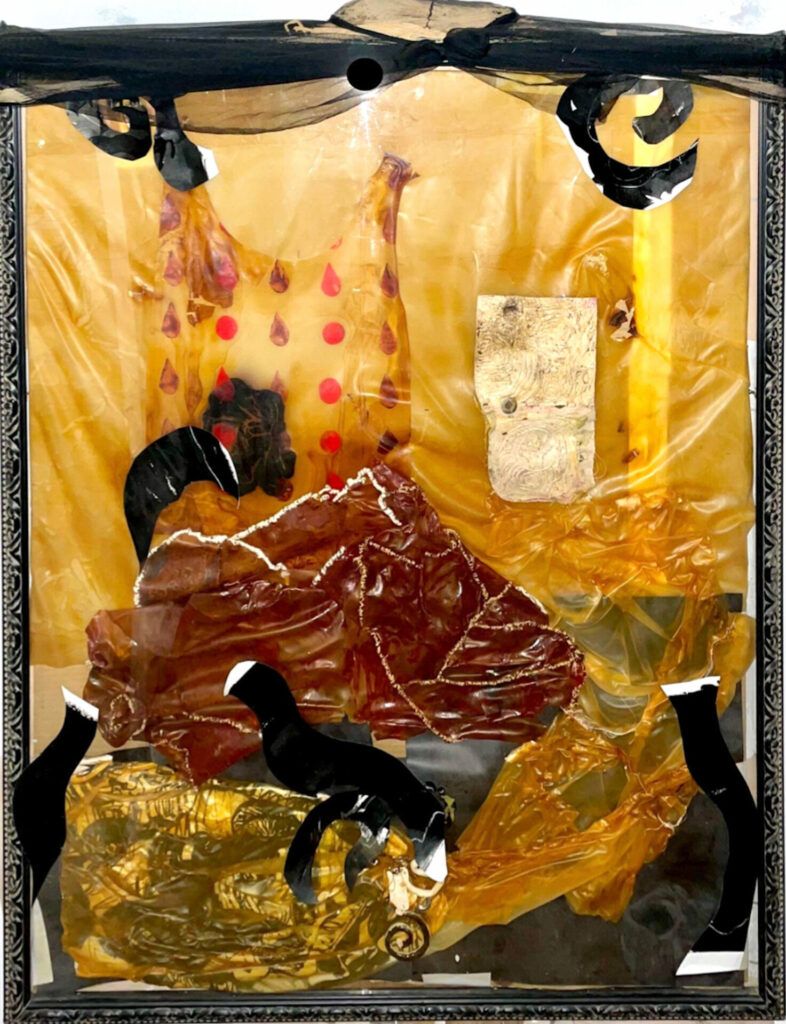

latex sheets, wire, grommets, fabric prints on Belgian Linen, thread, black

ink on bristol, chalk, yarn, acrylic, tulle), 38 x 47 inches, Image courtesy of

Gabrielle Vázquez.

Her methodology is slow and meticulous, stemming from a deep connection with material and the ways that it can tell stories. Depending on when you met her, you would know her practice by a different medium: is she a painter, printmaker, or fashion designer? Vázquez doesn’t see why she should have to choose. She is unconstrained by labels and dimensions: when she draws or paints, she later incorporates these elements into garments. She understands that materiality is more than just a study of surfaces, but, as she puts it, “an exploration into how art and fashion make us become embodied.”

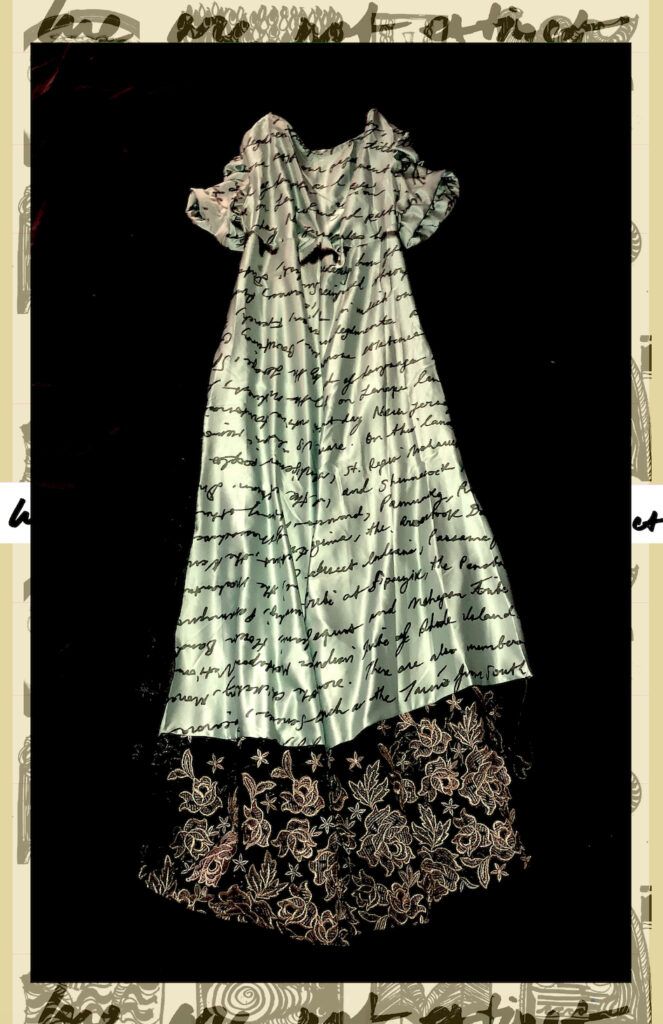

(Printed silk charmeuse, embroidered mesh scraps), Size 4 / 2 x 5 feet, Print size varies. Image courtesy of Gabrielle Vázquez

Embodiment, to Vázquez, is equally concerned with fashion and politics. In 2017, Vázquez worked on Palestinian activist Khader El-Yateem’s ultimately unsuccessful campaign to represent southwestern Brooklyn on the New York City Council. “I wanted to highlight in my canvassing parallels in the global struggles of migration, settler colonialism, and displacement in places as far apart as Puerto Rico and Palestine,” she expounds. Reflecting on her experience, she crafted a skirt inspired by art on the West Bank Wall. Why a skirt, and not a painting? Because Vázquez sees politics as being about our bodies, and fashion as a medium to explore this double entendre of the body politic. Walls separate us and keep apart our bodies, while messages, symbols, or designs placed on the body and its garments directly implicate our bodies in the politics they concern.

Three years later, Vázquez sewed together Belgian Linen embellished with digitally manipulated prints of her paintings to create a dress for New York State Senator Julia Salazar. Dubbed “The Census Dress,” the multi-colored patchwork piece encouraged participation in the 2020 census as part of a broader mobilization campaign. For Vázquez, the medium was the message: she hoped the dress would empower residents of the majority Latinx district in northern Brooklyn to stand up and be counted, centering their bodies in political processes often considered to be inequitable.

The journey towards embodiment is not one that Vázquez leaves at her front door. Consider her bathroom, the walls of which are adorned with an almost dizzyingly neon checkerboard of hand-painted stickers. The narrow room is a sea of hot magenta, candy red, and radioactive green, unexpectedly dotted with ephemeral drawings, such as one of a cat dancing in a maxi skirt. Some would call this an experiment in the ornamental, implying triviality, but Vázquez takes decorating seriously. There isn’t any part of her practice that is not intensely personal. Her practice allows her to reimagine the walls as garments, the space as an extension of the self. Any artistic endeavor with these goals, that which enables the artist or viewer to experience embodiment, could be labeled as fashion. “The way I see fashion isn’t concerned with mass producibility, market appeal — the sorts of hard skills that I was taught as a fashion student,” she explains. “Instead, I see fashion as fine art.” Vázquez’s work is an attempt to give form to her purpose, her pathos, and her politics.

Performance is part of that project, too. In 2018, Vázquez proudly marched down the street to commemorate International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women (I was chuffed to see her on Univision). Vázquez, however, wasn’t always interested in performance that occurs on a stage. It isn’t the mere intersection of art and activism that is noteworthy; it is that Vázquez uniquely understands politics as a platform on which art and fashion can bring to life a performance. “I’ve organized for ten political campaigns and briefly worked for a State Senator,” she recounts, “but I’m more focused on advancing social movements and changing cultural attitudes.” Vázquez is interested in martyrs, liberators, freedom fighters—think Lolita Lebrón, the Mirabal sisters—complex figures who leave complex legacies. Stories and headlines compete for our attention, and her politics could be labeled as an effort to make visual that which otherwise is relegated only to the written word. After all, the cable news loves a spectacle.

In the summer of 2020, Vázquez saw a random internet advertisement for a beauty pageant for women shorter than 5’6”. Vázquez didn’t need to think long about what her platform might encompass, but she felt unsure about the performance aspect. “Being called ‘shy’ as a kid pigeonholed me,” she recounts. “I allowed others to make me small and silent.” At the time, she was preparing to begin a Master’s degree in Anthropology. Suddenly, pageantry presented itself as an opportunity to study politics’ relationship to fashion and material culture via lived ethnography. She clicked on the advertisement.

National Pageant in Milwaukee, Wisconsin”, 2021. Live Performance.

Image credit Magic Dreams Productions / Petite USA.

That fall, Vázquez enrolled at The New School and was crowned Miss Northeast Petite. “At first, I felt like an artist undercover,” she laughs. Though she had entered a new environment, the components were familiar: the creation of aesthetic beauty for judgment and comparison, the packaging of self-expression into products for consumption. Vázquez saw the rules of the game but had questions to answer beyond the trite “What makes you unique?”—instead she grappled with what it means to be a person whose ancestors were colonized by the same nation for which she now performed her identity, and for whom she sought to represent on the world stage.

Beauty pageants are largely gender-based performances with divisions strictly categorizing women based on their reproductive history or marital status. As Vázquez navigated the opaque pageant system and her burgeoning sisterhoods, it seemed that she was becoming less bothered by her emic perspective. “I realized that I was actually embracing the performances as part of my creative practice and academic journey,” she reflects. Though it was two years and five more pageants before Vázquez was awarded her second title (Miss Boerum Hill, referencing the neighborhood in northwestern Brooklyn where she grew up and currently resides), her sights remained fixed on something beyond beauty.

Pageants are also sites of cultural expression, and for Vázquez there is no culture without politics. Throughout her performances and public appearances, she has become more steadfast not only in her political beliefs, but in the performance of them: when she appeared on stage draped in her own hand-made garments, the flowing words of the land acknowledgement that traversed her body enabled her to talk about history and culture. Though Vázquez never competed on an international stage or adjusted her makeup for the harsh lights of the silver screen, she never needed to win a single title in order to achieve her goals. What Vázquez gained from her late bloom into pageantry is a self-determination catalyzed by discomfort, a boldness that can only be cultivated under pressure. As she tells it, “I became embodied.”

Mixed Media (cotton, blue thread, linocut print superimposed onto image).

Print size varies, Image courtesy of Gabrielle Vázquez.

When Vázquez announced a panel discussion with five other Puerto Rican pageant queens living across the mainland United States, she intended to do more than gather information for her upcoming thesis (which questioned how this demographic might adopt decolonial perspectives while participating in pageantry). She sought to foster community and to build collective power among her pageant sisters. As two Puerto Ricans from New York, it is easy for Vázquez and me to forget that the diaspora flourishes beyond our Nuyorican tribe. It is easy to be proud of your culture in a city that celebrates it in an annual parade, and Vázquez gave her sister queens the necessary pride to assert their identities. In turn, they might return to their pageants, follow Vázquez’s example, and co-opt these platforms into spaces of cultural and political agency.

Like many artists, Gabrielle Vázquez is driven by a feeling. That feeling which compels her to create cannot be summarized in a word, rather it exists in the tension between her heritage, her media, and her politics. But unlike many artists, where others see contradiction, Vázquez sees an opportunity for embodiment. “When I turn the corner and make my debut on a pageant stage, I am the artist, the curator, and the art,” Vázquez proclaims. “Pageantry is rigid, but I own the narrative, and I become embodied.”