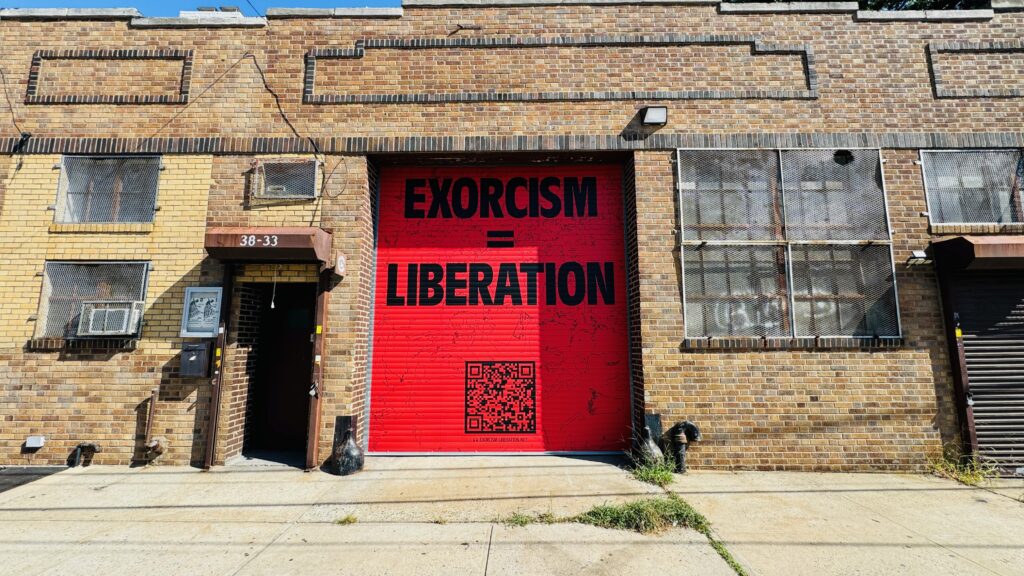

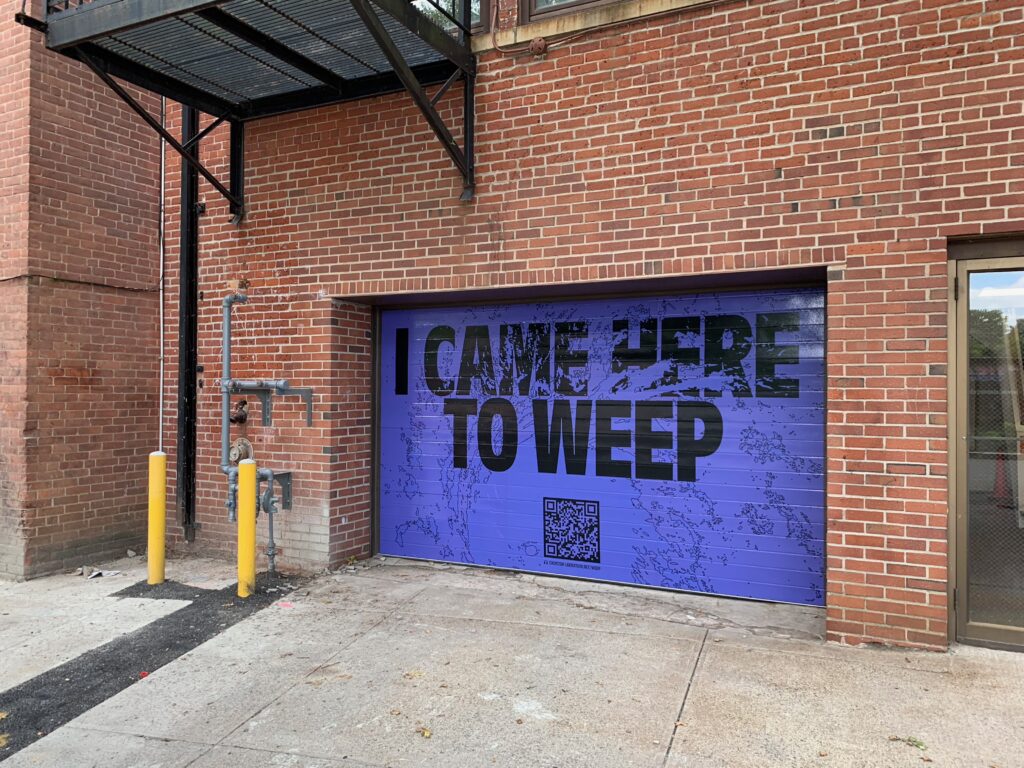

Imagine this: a huge red mural stretches across the façade of a building, with bold black letters that read “Exorcism = Liberation.” Next to it, an oversized QR code invites you to pull out your phone. You scan it, and suddenly you hear a voice shouting “¡El pueblo unido jamás será vencido!”, drums pounding, and a chorus of fragmented words unraveling Puerto Rico’s colonial history. There’s no stage, no seats. You’re out on the street, yet somehow, you’ve stepped into the piece—and you’re no longer just a spectator: you’re part of it.

This is the world created by Yanira Castro, a Puerto Rican multidisciplinary artist and choreographer based in Brooklyn. She was born on the island of Puerto Rico and moved to the U.S. at the young age of seven, when her family relocated to New Jersey. Castro studied at Amherst College, where she earned a BA in Theater and Dance and English Literature. She has worked extensively in dance and performance across the United States and has received two New York Dance & Performance Awards (Bessie) for Outstanding Production. Her work lives at the intersection of performance, installation, communal practices, and interactive technology. Since 2009, she has created under the name a canary torsi (an anagram of her name), a collaborative multidisciplinary platform for long-term projects. Castro has built a reputation for dismantling the traditional boundaries between artist and audience, prompting us to question who makes art and how we experience it. In her recent projects, I came here to weep (2023) and Exorcism = Liberation (2024), she has taken this vision even further: placing land, memory, and the body at the center of a ritual that seeks to unearth colonial trauma and, through collective action, release it. Through this, Castro has become a catalytic force, prompting a deep questioning of entrenched systems. In a context where colonial structures still shape the lives of Puerto Ricans, her art opens space for reflection, discomfort, and possibility.

This essay explores how Castro’s multimodal projects serve as an act of collective liberation, where bodily memory and participation become tools for confronting history. It considers her artistic evolution, her commitment to community-based practice, and the way her identity fuels a vision of art as both ritual and civic action.

Much has been written about Castro’s innovative approach to breaking down the division between performer and audience, but her work goes beyond mere participation. In her artistic world, performance becomes a ritual, not just a space of spectacle, but a shared event where bodily memory is activated and the community is invited to act on what is often repressed. In a 2010 interview about her work Wilderness, Castro reflects on her ongoing resistance to theatrical conventions: “I have long taken issue with a fixed division between audience and performance because it enforces a very specific relationship and gives the audience very little choice in how to participate in what they are witnessing” (Frank 2010). That piece, like many of her earlier works, broke down barriers by immersing audiences in environments where they were encouraged to move freely, interact with performers, or follow printed instructions. This disrupted traditional spatial hierarchies and allowed audiences to feel part of the work rather than remain passive observers.

In her most recent projects, this search for intimacy has taken on even greater symbolic power: the body as an archive and as a site of exorcism. In I Came Here to Weep, for example, Castro doesn’t just invite us to participate, she designs a series of rituals that participants must perform, such as cutting a guava, smelling the scent of herbs, and kneeling to press their bellies to the ground. These haptic and phenomenological gestures are carefully crafted to activate bodily memory and connect history and land. As Castro states: “Exorcism is the liberation of the body, and our memories are lodged in our bodies” (Nguyen 2024). Participating in these projects involves going through a process of release, of unearthing everything we’ve buried, consciously or unconsciously.

Land, both as a physical space and as a symbol, shows up again and again in Castro’s work. One of the recordings, titled What is your first memory of dirt?, guides listeners from a sensorial experience toward a reflection on property, borders, and belonging. This tension between personal memory and structural critique runs throughout her work. Her question encapsulates a key idea: the earth is not just the ground we walk on, but also the first place where we experience freedom and its accompanying limitations. That first time we touched dirt or got messy often brings back memories of playing outside, but quickly following this comes a reprimand, a rule imposed: don’t get dirty, don’t run, be careful. This seemingly simple question opens a powerful paradox: the earth is both a space of freedom and of restriction. This duality mirrors broader histories of colonization, where the land represents both belonging and exclusion; a place of nurture, and a place regulated by imposed rules.

In Exorcism = Liberation, Castro brings this question into the public space during the U.S. Presidential election. Through murals, banners, posters, stickers, and QR codes spread throughout cities with strong Puerto Rican communities like New York, Chicago, and Massachusetts, her project weaves itself into the fabric of everyday life. Unlike traditional political campaigns that use similar media to persuade or moralize, Castro’s work invites critical reflection, intimacy, and shared vulnerability. Each element acts as a portal to audio recordings designed to awaken colonial memory and demand bodily engagement. In these recordings, we hear artists like Melissa DuPrey reciting fragments of the Treaty of Paris of 1898, the document that formalized Puerto Rico’s colonial status under the United States, interwoven with bodily instructions like making a fist. That mix of voices, protest chants, and music creates a dense, uncomfortable atmosphere. Castro makes it clear that her aim is not to educate the public about Puerto Rico’s colonial history, but to have them physically participate in an act of political liberation. These performances do not happen in museums or theaters, but in everyday spaces. The street becomes a stage and the sidewalk a ritual site. By moving outside of art institutions, she rejects gatekeeping and invites the public who might not attend formal exhibitions to participate on their own terms.

What sets Castro apart is not only the aesthetic form of her work, but its social function. She does not position herself as an authority, but rather as a facilitator of spaces where memory, grief, and those difficult questions can be processed collectively. Her pieces are not closed spectacles but invitations. In that sense, we might say her true medium is relationship: between people, bodies and memories. During the development of Exorcism = Liberation, Castro collaborated with more than 25 community and arts organizations across three regions. From community gardens in Holyoke to cultural centers in Brooklyn, each activation was designed with and for the people living there. The project not only distributed materials, but created spaces for conversation, mourning, care, and action.

Castro has expressed discomfort with the word “community,” especially from within the diaspora. For her, what matters is not claiming belonging, but building real relationships through time, commitment, and listening. In her work, diaspora is not just a geographical condition, but a shared wound and also a starting point for imagining alternative futures. Her recent pieces show how being part of a diaspora intensifies both the desire for connection and the weight of history.

One of the most striking elements of Castro’s work is how she transforms everyday materials—posters, stickers, and signs—into something like portals. These objects are not decorative; they connect us and immerse us in states of reflection, forcing us to pause and become part of something larger. As the artist puts it: “These objects are like QR portals waiting for the human who sees a pin on a backpack that says ‘Dirt’ and wonders, asks to scan, and finds themselves listening to a story of migration and crossings” (Nguyen 2024). These acts, simple yet profound, speak to her ability to find political potential in everyday forms. Her artistic interventions do not impose meaning; they offer frameworks for experience. This insistence on vulnerability, co-creation, and listening as a form of resistance sets her work apart in an art world often dominated by ego and individual authorship.

We need more artists like Castro, artists who turn art into action, who build spaces where memory is honored and futures are rehearsed. Her work is a blueprint for how creative practice can serve as a civic engine, a ritual of gathering, and a rehearsal for freedom. As she herself insists: true liberation can only occur in the collective body (Nguyen 2024). In a world oversaturated with data, screens, and hollow discourse, committing to bodily memory, to the body as archive, as territory and as possibility, is a profoundly political gesture. Castro shows us that art, especially diasporic art, does not simply represent identity: it constructs it in action. Her work invites us to remember where we come from and to shake off what oppresses us. Because, as she insists, true liberation can only happen in the collective body.

Her artistic evolution reveals an ongoing search for forms that align with her political vision. From her early interest in disrupting theatrical conventions, to her recent use of interactive technology and communal rituals, Castro’s language has grown more open and collaborative. She has become both a performer and a host, making space for others to be seen, heard, and felt. In the end, what Castro offers is not a fixed ideology or a clear roadmap, but a practice of being together. She teaches us that performance can be a form of democracy: slow, imperfect, experimental and sacred.

References

- Frank, Andrew. 2010. “A New Language: Yanira Castro.” BOMB Magazine, October 2. Accessed May 10, 2025. https://bombmagazine.org/articles/2010/10/02/a-new-language-yanira-castro/

- Nguyễn Donohue, Maura. 2024. “What Is a Liberated Body? ‘Talking’ Exorcism = Liberation with Yanira Castro.” Culturebot. Accessed May 12, 2025. https://www.culturebot.org/2024/10/98679/what-is-a-liberated-body-talking-exorcism-liberation-with-yanira-castro/