In the ever-evolving landscape of Puerto Rican art, few voices carry the depth, rigor, and emotional honesty of Efrén Candelaria. Not just a painter, but a thinker, and cultural worker, Candelaria’s practice avoids easy categorization. Born and raised in Santurce, Puerto Rico, and currently based in Chicago, his work is rooted in the complexities of diaspora, memory, and personal truth. From early experiments with minimalism and installations to his most recent large-scale paintings, his journey as an artist mirrors the displacements and contradictions of the Puerto Rican experience.

What makes Candelaria’s practice stand out is its refusal to perform identity, even as it returns to spaces, forms, and emotions of Puerto Rican life. His art is not an aesthetic of nostalgia or resistance, but a poetic exchange with architecture, territory, and belonging. Whether depicting the ruins of vernacular homes or abstracting urban landscapes into fields of color and line, his paintings explore what it means to dwell: in memory, in the body, and in a history of colonial rupture.

Efrén Candelaria’s path into art was shaped as much by discipline as by intuition. Before he identified as an artist, he was a competitive soccer player in Puerto Rico, dedicating his youth to rigorous training and the collective ethos of team sports. He explained that everything he knows about persistence, structure, and effort started with soccer. That athletic discipline would later become the foundation for his studio practice. Yet by the late 1990s, he sensed a shift coming. After two years studying at the University of Puerto Rico, he realized: “If I don’t leave the island now, I won’t become what I need [to be].”

Candelaria moved to Miami in 2000 to study at the University of Miami. What he met there was a cultural shock. Despite the city’s reputation as a Latin American Hub, the university was overwhelmingly white, upper-middle-class, and disconnected from any Caribbean or Puerto Rican context. He struggled with the English language, more fluent in French at the time, and felt alienated. But this linguistic limitation helped further his artistic journey, it forced him to stop overexplaining and simply create. As he elaborated in the interview, the best lesson he got from his professors was: “[Learning] how to make it. Don’t try to give it meaning. Just make art.”

Through mentorship from sculptor Tim Curtis, Candelaria began to connect his academic and technical background with a deeper conceptual approach. He started integrating theory, poetry, and intuition into a system of thought that would later become his signature process. Still, at this early stage, he rejected nationalist readings of his work. “I was an artist who happened to be Puerto Rican… not a Puerto Rican artist.” That posture, rooted in a desire for universality, would shift overtime, but it marked the beginning of his identity as a serious, conscious maker.

After graduating, Candelaria moved to New York and then Chicago, delving headfirst into the art world while also feeling increasingly disillusioned by its mechanisms. He exhibited in commercial galleries, took part in residencies, and experimented with minimalist drawing and installation. But over time, the pressure to produce work that could be marketed or explained suffocated him. The straw that broke the proverbial camel’s back came when he was helping set up an installation by Roy Lichtenstein at the Art Institute of Chicago. When he was informed the work was valued at 80 million dollars, he had a moment of crisis. “This shook me… I need to do something because this is not me.”

It was around this time that Sobremesa Chicago was born, a project that would reshape his relationship to art and community. Alongside two childhood friends, Candelaria co-founded a collective that combined food, storytelling, and art as tools for cultural memory and economic resilience. They hosted communal dinners, curated visual interventions in informal spaces. “Let’s do good and do well” became their mantra. Through Sobremesa, Candelaria began to fully embrace his identity as a diasporic Puerto Rican artist, not because he had to stand for anyone, but because he now understood the emotional and historical weight of displacement. “It was the first time in all those years I had a full reflection of what it had meant to leave.”

This project also reoriented his sense of artistic purpose. No longer concerned with institutional validation, Candelaria stepped away from studio works altogether for almost a decade. When he eventually returned in 2019, it was as a maker deeply attuned to place, memory, and personal truth. The seeds planted through Sobremesa would blossom in his later series, not only in content, but in philosophy. A commitment to art that is intimate, precise, and human.

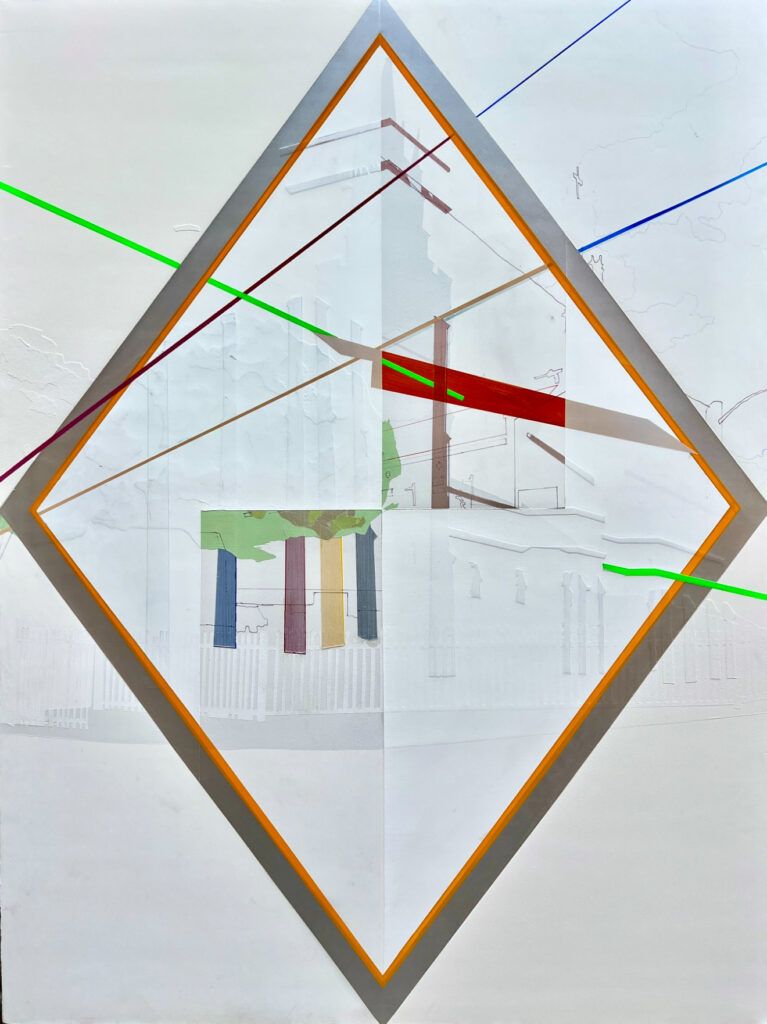

His return to studio painting came with a strong clarity of his purpose. The break had not dulled his instincts but sharpened them. What came was his famed series Del Reino y de la Rueda: Nomenclatura para Pinturas Coloniales, a body of work that marked a dramatic shift in his visual language and thematic depth. A series characterized by richly textured surfaces, intense chromatic fields, and the recurring silhouette of the Puerto Rican house. These “casitas” became central, not as nostalgic representations of national identity, but as formal and emotional structures through which to explore grief, memory, and resilience. He clarified that they’re not homes, but instead architecture as a metaphor for how we hold memory and pain. These paintings, layered with color theory and symbolic geometry, carry a meditative force.

Candelaria was inspired by his firsthand experiences during Hurricane Maria in 2017. Trapped in Puerto Rico for around 2 months, when he finally left the island, he felt that he was fleeing. “I was leaving behind my mom, my grandma… and I felt very guilty about it.” That guilt would transform itself into a visual language. Rather than depicting the catastrophe explicitly, he looked to ignite a conversation about the individual.

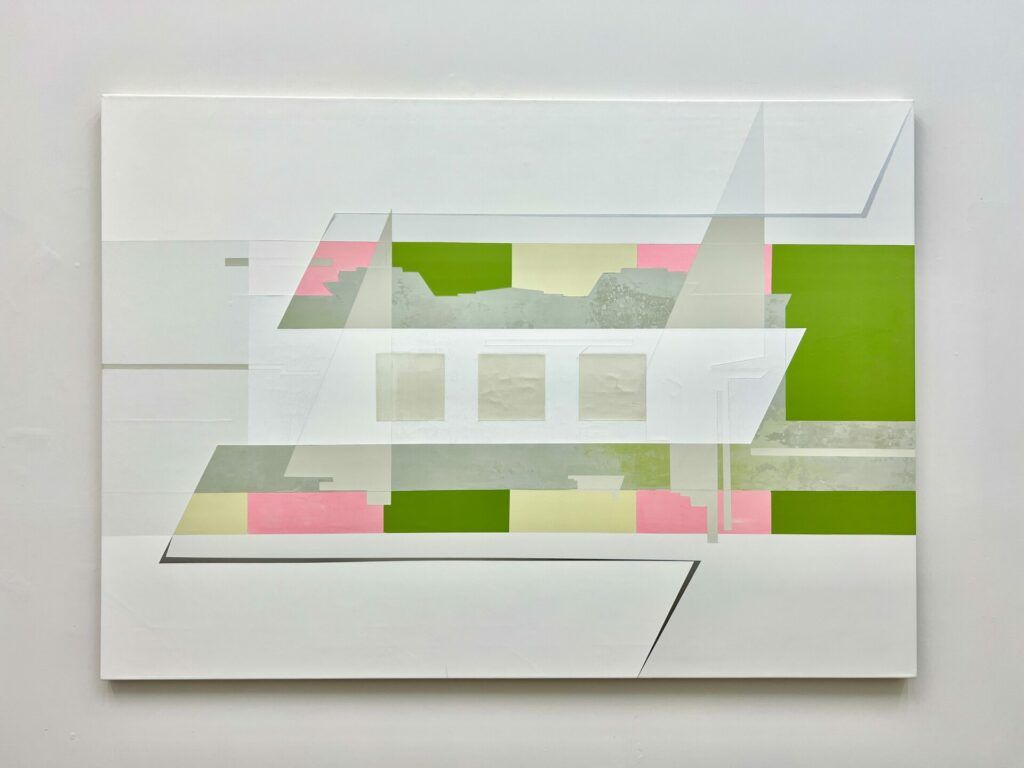

If Del Reino y de la Rueda was a return to painting, Machuchal en Blanco was a return to origin. In 2023, Efrén Candelaria was invited to exhibit in Puerto Rico. There he saw how his childhood neighborhood of Machuchal, once a working-class section in Santurce, had been drastically transformed. Years of gentrification had ravaged the community. The cultural heart of Machuchal had been gutted by real estate and tourism. Rather than depict this violence, Candelaria turned to poetics. The series consists of white-on-white compositions, delicate architectural silhouettes rendered in light, silence, and negative space. The choice of white wasn’t a neutral one. It carried with it the totality of color, the language of mourning, and the aesthetics of Latin American abstraction.

The paintings memorialize the homes and corners of his youth, some still standing, many already gone. But this isn’t just an exercise in nostalgia. It’s a quiet, rigorous critique of urban erasure. “These [spaces] were important in the development of my idiosyncrasy.” Unlike overt slogans of activist art, Machuchal en Blanco demands restraint. There are no protest signs, no figures shouting. Instead, there is light, stillness, and grief. These are strategies that require patience from the viewer. This refusal to make trauma digestible or decorative is what gives the work its power.

The shift to white also marked a departure from his earlier chromatic vocabulary. Where Del Reino was vibrant, Machuchal is sparse and almost silent, yet still emotionally intense. The series stands as one of Candelaria’s most profound statements. A love letter to a place, and a refusal to forget.

Efrén Candelaria’s paintings hold a highly disciplined, almost architectural structure. His process begins with an emotion. A visceral, bodily reaction to a place, memory, or moment. From that he moves into theory, reading interviews, journals, and artists’ reflections. He writes extensively, asking himself questions. Only then does he begin to build his thought system, composed of multiple steps, that he must fulfill in the creation of a piece. It’s not a linear order, and the steps can vary, but every painting must pass through them. He explained it like a checklist, “usually when I can cross out the last one… then I’m [almost] done.”

Materially, Candelaria favors water-based polymers and acrylics, not just for their visual properties but for practical reasons. He prefers Golden acrylics because: “the pigment is strong, lasts longer, and travels well.” For an artist who moves between Texas, Chicago, and Puerto Rico, these details matter. “Art is only effective if the viewer can engage with and see themselves through it.” For him, portability is not a compromise but a necessity. Additionally, color, light, texture, and surface also serve as vocabulary. They are always in service of something deeper. A moment of recognition between the viewer and object, a subtle shift in feeling. “Any way they interpret it is as right as any art historian’s interpretation.” He wants to give you space to relate.

Toward the end of our conversation, I asked Efrén Candelaria what advice he would give to young Puerto Rican artists living in the diaspora. After some deliberation, he answered: “Just do it. Don’t think it.” Echoing what his professors taught him. For him, failure isn’t about reception, rejection, or quality. It’s about not following through. “The only real failure is not executing. Everything else is part of the process.” This ethos, rooted in years of discipline, detours, and discovery, is what gives his work its emotional clarity.

In the end, Efrén Candelaria is not interested in following trends. What matters to him is honesty. “If you want to be original, be honest.” In his case, honesty is not only personal but cultural, architectural, and historical. It’s the sound of a neighborhood being erased. It’s the light that remains after a house falls. Candelaria does not offer answers, instead he offers space. His paintings are not declarations, but invitations: to remember, to feel, to dwell. In a world of noise, urgency, and spectacle, his work moves differently. It lingers and it listens. In doing so, it gives form to something deeper than representation, truth.

References

- Candelaria, Efrén. 2025. Personal interview conducted by Luis A. Bonilla Robles. April 28, 2025.

- Centro (Center for Puerto Rican Studies). 2022. Efren Candelaria: Artist Profile. Diasporican Arts in Motion. https://centropr.hunter.cuny.edu/artists/efren-candelaria/

- Contratiempo. 2021. “De la importancia capital: la validación y el reconocimiento.” Contratiempo Magazine, April 29, 2021. https://contratiempo.org/de-la-importancia-capital-la-validacion-y-el-reconocimiento-soy-artista-y-productor-social/

- El Adoquín Times. 2021. “El artista Efrén Candelaria inaugura exposición en Galería de Arte de Sagrado.” El Adoquín Times, October 19, 2021. https://eladoquintimes.com/2021/10/19/el-artista-efren-candelaria-inaugura-exposicion-en-galeria-de-arte-de-sagrado/

- El Nuevo Día. 2021. “El artista Efrén Candelaria inaugura exposición en Galería de Arte de Sagrado.” El Nuevo Día, October 17, 2021. https://www.elnuevodia.com/entretenimiento/cultura/notas/el-artista-efren-candelaria-inaugura-exposicion-en-galeria-de-arte-de-sagrado/

- inSagrado. 2021. “Efrén Candelaria inaugura su exposición en la Galería de Arte de Sagrado.” inSagrado, October 20, 2021. https://insagrado.sagrado.edu/efren-candelaria-inaugura-su-exposicion-en-la-galeria-de-arte-de-sagrado1/

- Puerto Rico Art News. 2021. “Exposición de Efrén Candelaria en la Galería de Arte – Sagrado.” Puerto Rico Art News. https://www.puertoricoartnews.com/2021/12/exposicion-de-efren-candelaria-en-la.html

- Reyes-Veray Collection. n.d. Efren Candelaria. https://coleccionreyesveray.com/efren-candelaria/

- Tai Modern. n.d. Efren Candelaria. https://taimodern.com/artist/efren-candelaria/

- Efrén Candelaria Studio. n.d. Efren Candelaria Studio. https://www.efrencstudio.com