A lot of times when something shows up in a painting, it’s because I’ve been thinking about it for years before – Marisol Ruiz.

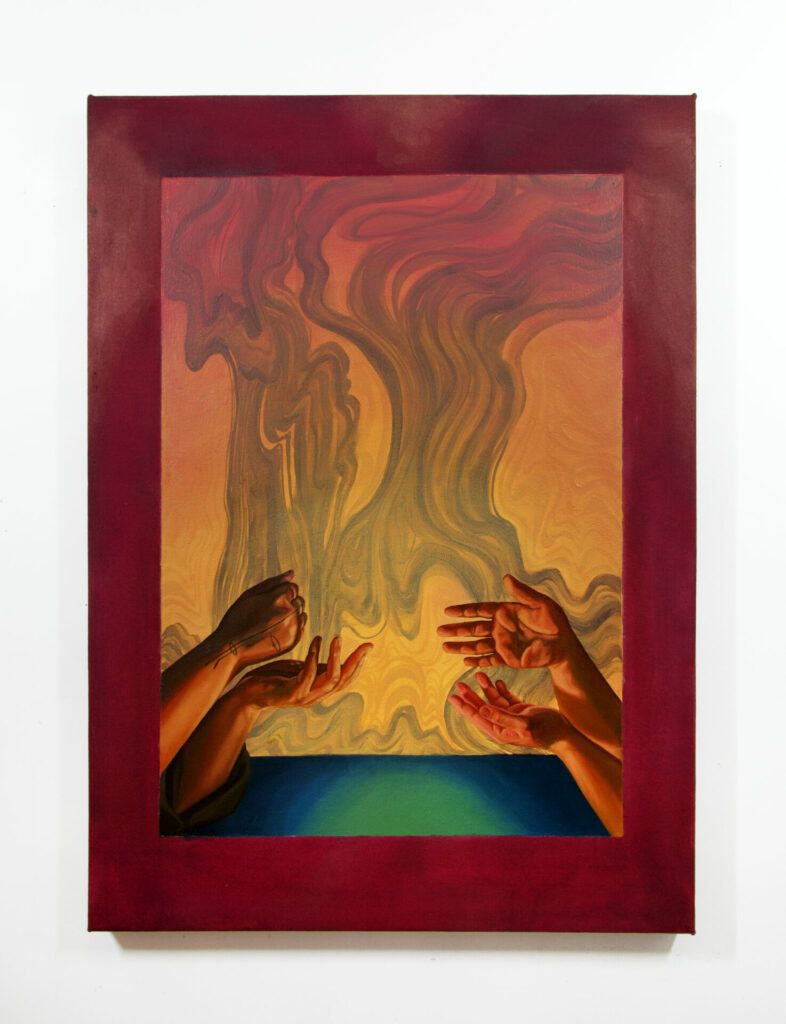

The importance of memory, the ethereal and the intangible is captured in Marisol Ruiz’s work. The artist grew up in Guayanilla, Puerto Rico, which greatly influenced her artistic production. Marisol completed her studies at the Maryland Institute College of Art in 2020 and is based in Brooklyn, New York. Her primary mediums are acrylic and oil, canvas and panel. She explores the diasporic experience through an intimate meditation on memory. Her art represents a set of imagined memories both collective and imagined that arise from her Puerto Rican heritage and subconscious. Her childhood is an important source for her subject matter, composition, and color choices.

In our conversation on April 23, 2025, we discussed key factors that shaped her work, the specific reasoning behind the subject matter of her work, and how she arrived at it. We also discuss how she seeks to represent these memories while honoring the people in her life responsible for passing the oral history onto her. We even commented on the reason why she incorporates elements of nature in her recent works, further enriching their message. Marisol has been featured in various group exhibitions such as Off-Kilter, Untitled Art Fair, High Maintenance, Puros Exitos, and De Colores: A Symbol of Latin American Empowerment.

This interview has been edited for clarity and concision

Karelys Rivera: Your work is essentially the representation of personal and collective memories. What made you embark on this path of representing memories?

Marisol Ruiz: When I started painting at MICA (Maryland Institute College of Art), a lot of the classes forced you to think about your identity. Over the four years, I had been thinking about what it means to be Puerto Rican and live here. I started thinking of memory as a layered concept. Then it slowly narrowed down into my own life. I found it really interesting to be the keeper of our oral history. There were so many memories of growing up in Guayanilla, having experienced so many natural disasters and hurricanes, that’s when I decided I needed to hold on to all these memories that have been given and passed on to me because they’re going to be forgotten. I feel like there’s power in being able to hold on to these stories and to be able to paint about these people.

KR: Regarding your painting Show Room (2019) you talk about painting someone without painting their body. Can you talk about how these ideas and thoughts came and how to interpret them onto the canvas?

MR: I think Show Room was one of the first paintings where I started to think about that memory. I started to think about the objects that you own, and how that in itself is a portrait. When you enter a room, without people being there, the objects say so much about them. It’s all connected to thinking about portraits in a different way that wasn’t using the body, because I wanted to think about portraits outside of that.

KR: In your art I can see some similarities to the work of other Puerto Rican artists in terms of color choices and the representation of spaces. Have any Puerto Rican artists served as inspiration at some point in your career?

MR: There’s so many, going back into Art history, José Campeche was somebody that I referenced here and there. I also looked a lot at Myrna Báez’s work, and Rafael Tufiño. I’ve looked at a few from that time, and then it all jumps to contemporary artists that are alive right now. I look a lot at Edra Soto and Nora Maité Nieves’work, something that they’ll paint about stays in my mind. Even my friends Maru Aponte and Natalia Sánchez. This is an abbreviated list of people I’ve been thinking about here and there. Every time that I see their work, there’s something that stays with me because it’s also similar things that I think about.

KR: Many artists represent elements of Puerto Rican identity through the use of national icons like the flor de maga and el coquí, which could sometimes be a cliché. In your work, you capture that Puerto Rican essence in a more domestic version, which is not usually represented. How is this connected to your experience living on the rural side of the island?

MR: It’s interesting, because I use some of the cliché stuff, but I try to think about it in a different way. The flor de maga, for example. I dyed a canvas using hibiscus flower because I could not find flor de maga. Growing up in Puerto Rico, there were so many competitions for, a poster, a postcard, whatever it was, and it was always el coquí and la bandera, I feel that I got that out of my system, I did it so often, and I’ve thought about it so often that I think about them differently, especially having been in the United States for so long.

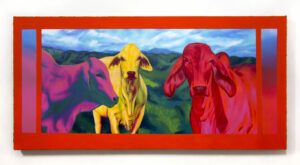

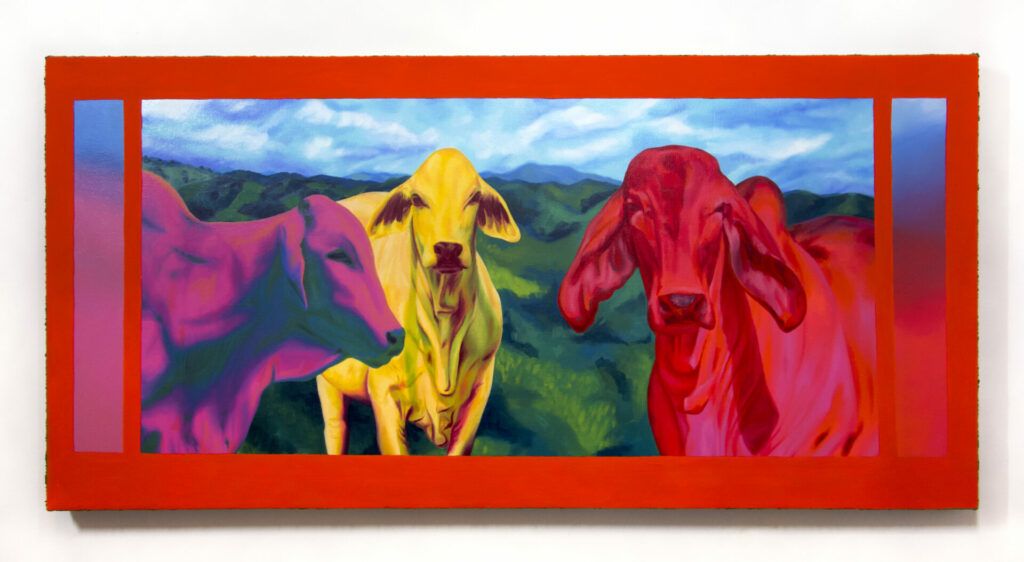

KR: In paintings such as El Pasto (2024) and Go! (2024) you use hibiscus pigment and plantain leaves. Can you talk a little about the process and what inspired you to connect nature with your work in such a direct way?

MR: I can talk specifically about El Pasto. I had been thinking a lot about where I grew up, what I looked at every day. Growing up, around the house there was a lot of land, so there were a lot of cows. And I was thinking about the cows a lot, and how they have this sort of, like familiar thing. At the time, I was also thinking about how I depict memory in my work, the memory that is carried with the things that we use. I started to think about oil paint, and how it has its own history, and its own connotation. Well, how can I add more memory to this, that it’s more personal, and so that’s why I started to use the plantain leaf and the hibiscus. I had thought about, like the sound that the plantain leaves make when the wind blows, that’s why I framed it that way.

KR: The usage of color is characteristic in your work. You’ve mentioned before that color helps convey emotions and vibrancy from your memories growing up in Puerto Rico. Pink, violet, yellowish, and orange tones predominate in your work. Is there a specific reason why you use these colors?

MR: I naturally have gravitated to them because of two big reasons. My dad used to plant a lot of flowers. The whole house was just full of flowers, and a lot of these colors are specific, like that pink that you’re talking about, usually it’s because I’m thinking about the pink mussaenda trees. My dad has planted a ton of them because I love them. When I think about that pink, I think about that tree, because it’s like a childhood love of mine. When I think about the yellow and these oranges, I think a lot about the houses in Puerto Rico. Maybe it ‘s like a subconscious thing, because I also ended up going to La Ramos (Escuela Especializada en Bellas Artes Ernesto Ramos Antonini), and everything in Yauco is that bright and yellowy.

KR: A lot of people tell you that your artworks reminded them of a loved one, and I am not the exception. Some of your paintings made me think of my grandmother, who has always had orchids her entire life. Many of your works depict orchids of different colors. Could you tell me more about the reason or symbolism behind them?

MR: It all started because I was thinking about the mother figures in my life, and having grown up in Guayanilla, a lot of the mother figures love flowers, especially orchids. These women have been like mother figures to me throughout my life. I had many, and all of them were older women who had some form of flower collection, but mostly, most of them had a big orchid collection. In the same way that the idea of memory is like an upside down triangle. It’s the same thing with orchids, those orchids connect me to those people. Most of them have passed away, some of them haven’t. But it’s one of the few things that when I paint them, it’s my way to honor these women who had this intense effect in my life that was so loving and caring.

Over the years, Marisol has distinguished herself by creating her own style that captures a different version of Puerto Rico than the one we usually see, a more intimate and everyday view. By using elements such as color, and objects like furniture, railings and tiles, she dives into the viewer’s memory. Taking inspiration from great Puerto Rican painters who have shaped Puerto Rican art history, but also learning from other contemporary artists, Marisol Ruiz has created a unique style. The usage of organic materials are also an important part of her work, as they are a direct way of including representative elements of Puerto Rico in a way that is not only figurative but also literally part of the work.