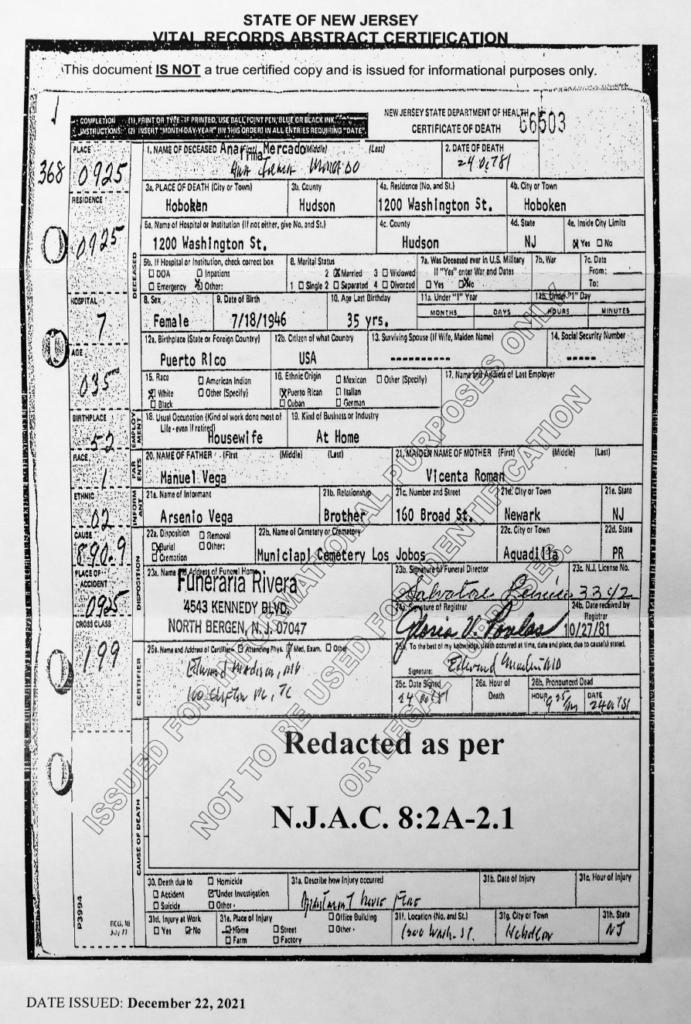

On October 25, 1981, Ana Mercado lost her life along with her father, husband, and four children. An activist advocating for tenant rights in her community, she succumbed to the flames that engulfed her apartment building on 1202 Washington Street, as she struggled with her family to escape from the fifth floor. Ana’s brother Arsenio, remembers receiving the devastating call and the painful job of having to identify their bodies in a small room amidst the corpses of other families from neighboring floors.

The fires that began burning through the barrios of the South Bronx just a few years before, had now followed Puerto Rican families to Hoboken. The collapse of the area’s shipping port economy which once drew lower income residents to purchase affordable housing and take on factory jobs in the area, would soon beckon young professionals for its short commute to Manhattan with waterfront views. To make room for this new white collar class, Hoboken’s City Council weakened rent control laws and permitted landlords to make rent increases which began a purge of families who had no recourse but to move. The city continued to pass further protections for landlords which made it easier for them to take tenant removal into their own hands. The families that chose to stay endured threats and intimidation, and later suffered through a wave of arsons that resulted in the displacement of thousands and the untimely deaths of 56 residents, most of whom were Puerto Rican.

In his series, The Fires, Puerto Rican photographer Christopher López mines this painful history to address the deadly scourge and cover-up which paved the way for Hoboken’s “renaissance.” López, who was born in the Bronx during the 80s and raised between New York and New Jersey, has felt this displacement intimately. It is through this close lens that he retells the story of the fires, a generation later, piecing together a fragmented past of those lost through found and constructed photographs, interviews from relatives and rescued personal effects.

Resisting the impulse to make a photographic typology or adhere to an imposed seriality in the work, López meets each victim’s story with its own dignity and attention. Sometimes it’s helping the families he meets carry on the memory of their loved one through ceremonial remembrance. In other instances, he traces their loss to the life shaping events that unfolded after.

Maria Feliz, lost four members of her family including her brother Charlie in an arson fire at the Pinter Hotel in 1982. After the fire, her mother, Noemi, began abusing drugs to cope with the grief of losing her son. Maria was removed from her mother’s custody at the age of seven and remained estranged for most of their lives. Noemi died in 2020 from complications of drug use. This image was made on Noemi’s birthday which Maria celebrates annually with her three sons.

Ángeles Pagán was 16 years old when she moved from rural Aguas Buenas to visit extended family in the states. Finding work as a seamstress, she made a permanent move to Hoboken to pursue a better life. But, in the years she’s lived there, the fires became a known violence that touched everyone in her community. In the winter of 1982, Ángeles and her family narrowly escaped a fire in their building at 223 Madison Street. She recalls the firefighters attempts to rescue her children as she inhaled billows of smoke—smoke that she says gave her permanent lung damage. That same year, Ángeles lost a close friend who died in the Pinter Hotel Fire, just blocks away, which killed 12 people.

For many, surviving the fires did not save them from the precarity of finding affordable housing or protect them from further financial hardship. In one of López’s most telling portraits, the generational legacies of urban renewal and housing discrimination can be observed as Ángeles Pagán poses with her daughters in their shared apartment inside Andrew Jackson Gardens, the only public housing project in Hoboken. They sit for the photograph stoically with the dresses their mother made for their sweet sixteen.

While the stories of those who stayed in the area are moving, another powerful component of the work is the way López follows the surviving families from the locus of the fires to other parts of the country, revealing the continued scattering of a people. The locations where he meets his subjects chart a particular migration as he tracks down families who hail from different regions of Puerto Rico, at one time settled in New Jersey, and now live in zip codes that span across several states.

A recent study examining homeownership trends amongst Puerto Ricans living stateside, found that stable housing is still elusive for many families generations after these periods of the arson-for-profit fires, particularly in larger metro areas. As families have continued to leave the island steadily since the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, new residents are encountering housing shortages once they reach the states.1 Outcomes improved only when migration patterns dispersed into areas where there were less established Puerto Rican communities —supporting the notion that Boricuas are forced to keep moving and rebuilding to survive.2

Arson for Profit series. Image courtesy of Christopher López.

Ángeles Pagán (center), with her daughters, Mary (left), and Gloria (right), at their apartment in Andrew Jackson Gardens, the only public housing project in Hoboken. As the city gentrified, many Puerto Rican families were sent to the projects for housing. Today, like much of the public housing in the Northeast, tenants of the projects are constantly under threat by encroaching development and the prospects of “renovating” or privatizing the buildings.

Curator Okwui Enwezor once stated:

The formation of a diaspora could be articulated as the quintessential journey

into becoming; a process marked by incessant regroupings, recreations, and reiteration. Together these stressed actions strive to open up new spaces of discursive and performative postcolonial consciousness.3

In many ways, The Fires follows this journey into becoming; It is through López’s “regroupings, recreations, and reiterations” of photographs that a counter-archive of Puerto Rican life emerges. Through his insistence of naming these events, dismissed accounts are given authority. In his construction of poignant still-lifes and defiant portraits, grief is honored and resistance is heroicized. The evidence he painstakingly constructs is not merely an attempt to rectify history so much as a space for the reclamation of it.

It was a fitting tribute for López to show this work for the first time in a community space like the Hoboken Historical Museum, a gesture that interrupted the linear history of the city while honoring the local families who contributed to the project. It feels as though López made this work primarily for the victims who were shaped by these events. But, by taking it upon himself to author new ways of preserving and engaging with the material past, we are charged as viewers with the responsibility of preventing these horrific acts from happening again.

As an artist, López believes there is potential for the archive to open up new ways of shaping public memory, specifically, revealing the flawed ways that communities of color have been misrepresented historically. “There is a particular kind of shaming commonly attributed to violent displacement that is rarely spoken of in our communities”, he says. “Challenging these perceptions are at the center of this work. I want to rehumanize our notions of place and our connectivity to them.”

Modesto Echevarria was killed along with his younger brother, Javier, in an arson fire at 67 Park Ave in Hoboken on October 13, 1981, Separated from their mother in the blaze they were found days later together in their bathtub.

References

- Joel Cintron Arbasetti “‘Boricuas’ in Florida at Epicenter of Housing Crisis,” Centro de Periodismo Investigativo, Sept. 2022.

- Department of Sociology, University of Pennsylvania, “Geographic dispersion and racial disparities in homeownership among Puerto Ricans,” 2023, 14-19.

- Okwui Enwezor, “A Question of Place: Revisions, Reassessments, Diaspora.” In Transforming the Crown: African, Asian, and Caribbean Artists in Britain, 1966-1996, edited by Mora Beauchamp-Byrd and M. Franklin Sirmans. New York: Caribbean Cultural Center, 1997, 80-88.