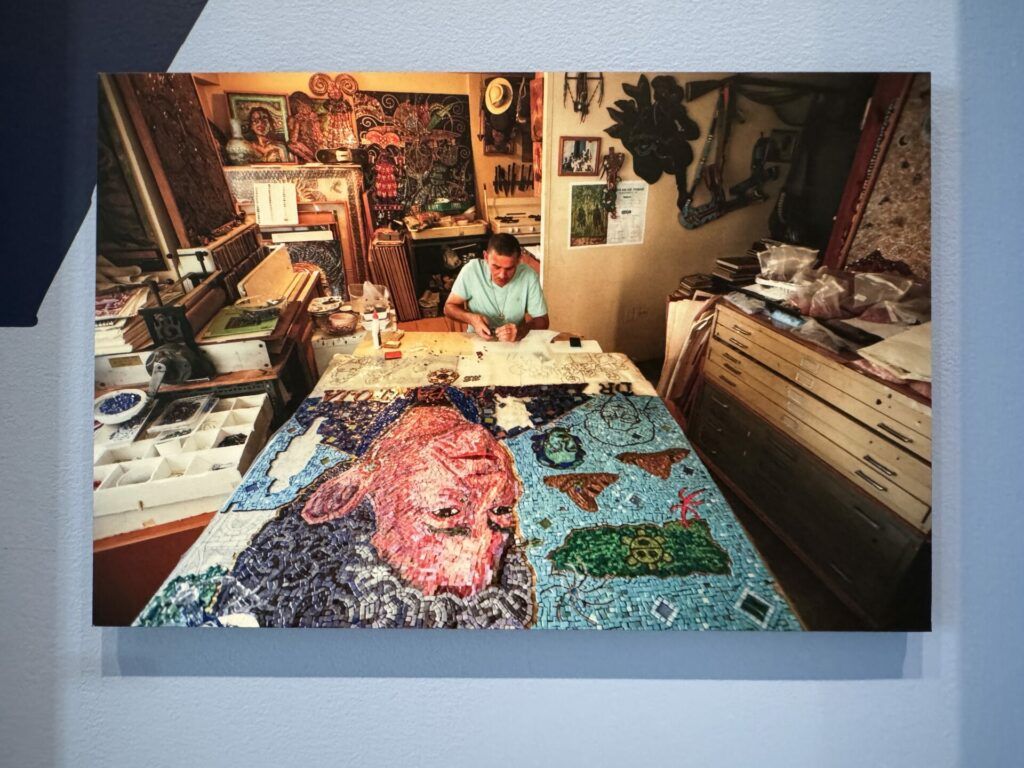

Byzantine Bembé: New York by Manny Vega through December 8, 2024, at the Museum of City of New York. Pictured above: Manny Vega. Bomba Celestial. 2009–2010. Collection of Bobbito García a.k.a. Kool Bob Love.

Byzantine and Bembé seem like unrelated words that should not be in the same sentence, even less in the title of a contemporary art exhibition. The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was founded in 330 CE, while the word Bembé is originally a West African drum-playing ceremony to call on Orishas, which acquired the general meaning of party in Puerto Rico. Working with curator Monxo López, Manny Vega presents cultural diversity as the basis of his artistic proposal.

In a short interview with the artist accompanying the exhibition, Vega narrates how the experience of the Puerto Rican diaspora, to which he belongs, was always in relation to the experiences of other ethnic groups growing up in East Harlem. For this reason, the curator Monxo López characterizes the pieces as “tales of New York’s urban diasporas.” However, what does this have to do with Byzantium? Mosaics constitute the majority of the works in the exposition, and this is an artistic technique that experienced a boom during the Byzantine Empire. Nevertheless, Vega is appropriating the term Byzantine in a deliberately loose way. He uses the term in the same way it is common to hear words like Renaissance and Baroque (15th through the 18th centuries) used as adjectives and not necessarily to convey a strict sense of these art historical periods. Like putting tiles together to form a picture, the artist accommodates historical references to create his “own modern-day renaissance,” as established in his statement on a wall panel.

Though mosaic originated thousands of years before the advent of this empire and has been employed by multiple cultures, it is undoubtedly a characteristic artistic technique in Byzantine art. At its height of expansion, that empire stretched across the coasts of the Mediterranean Sea and most of the Black Sea’s shores; it subsumed multiple cultures into one political and religious macro-project. It would be an understatement to say this was a geographically, religiously, and economically complex period. This complexity is another reason the term is helpful to the artist who developed his work in the culturally diverse space of New York City.

Contextualized as a multicultural artistic expression that had a significant development at the hands of the Byzantines, this proper noun becomes useful in Vega’s resignification of the New York diasporas. Mosaic has been present in New York: “Street walls, subway stations, cultural centers, and business facades,” as López explains in another panel. Vega grew up knowing mosaics as part of his environment, not only in the streets but also at home, and even while working as a young man, he had a significant encounter with this type of art.

In the interview at the show, Vega narrates how he began his mosaic-related practice by engaging in beadwork with his sisters from a young age (this is, of course, a different technique, but follows the same principle of using small pieces to create a more extensive work). On the other hand, López explained in his curatorial text that the artist’s first job was as a security guard at the MET Cloisters, where Vega saw actual Byzantine artworks and other pieces from the same period, like stained glass and frescoes. Thus, this is a very personal practice, intimate even, but, at the same time, connected to his community, one that is composed of multiple parts and backgrounds. Instead of a melting pot with a homogenous result, Vega presents New York as an artwork made from multiple different pieces that create a harmonious picture in which one can still identify its components.

In addition to the symbols and representations from the art itself, another way in which Vega refers to his relationship with his ancestral land is through his practice of printmaking. In the late 1940s, printmaking became one of the most outstanding artistic productions in the archipelago of Puerto Rico. In fact, this technique has been so important to Puerto Rican art development that in 1970, the Bienal de San Juan del Grabado Latinoamericano y del Caribe (San Juan Biennial of Latin American and Caribbean Prints) started. Thanks to this event and its further hostings, printmaking became an essential point of contact between Caribbean artists and their diaspora siblings. To offer a telling example, one of the most recognized artists in the history of Puerto Rican art, Rafael Tufiño, cultivated printmaking extensively. Tufiño was born in Brooklyn, moved to San Juan as a kid, and was involved in the origins of the Taller Boricua in New York, an atelier that also produced prints. Furthermore, mosaics by Rafael’s daughter, Nitza Tufiño (also an excellent printmaker), today identify the train stop at 103 St. as a Puerto Rican community: El Barrio. This stop leads to the same community that gave birth to the first museum of Latin American art in the U.S., El Museo del Barrio (sadly, the recent rebranding of this institution has removed the word “Barrio” from its name, opting to name it El Museo). Thus, the significant presence of woodcuts in Vega’s show is another way his work embodies his diasporic experience.

The exhibition is divided into three main areas, titled “Música,” “Figuras,” and “Justicia,” but Vega’s artworks go beyond. Culture, spirituality, and heritage blend as he captures his artwork’s people, instruments, and moments. Additionally, the pieces where he apparently moves away from religious subject matter are the ones where his everyday-life spirituality is most visible. For example, the “Música” section of the show is dominated by depictions of Bomba playing and dancing. Bomba, an Afro-Boricua music and dance, grew out of the religious practices of enslaved black people brought to Puerto Rico from Africa through the Transatlantic Slave Trade. The percussion developed by these ancestors –alongside indigenous music instruments and influence– is the basis of most Puerto Rican music, from Danza Puertorriqueña to Reggaetón.

Hence, the depiction of Vega’s Tito Puente playing timbales, a modern percussion instrument, is more than just a portrait: it also establishes the continuity and importance of the African and Indigenous elements at the base of Puerto Rican national idiosyncrasy. In this piece, along with the timbales, are other indigenous instruments like güiros and maracas, which are fundamental in Salsa, a music genre developed by Caribbean diasporas in New York alongside the influence of other Afroamerican music genres like Jazz. In this way, the three main thematic axes are present in one artwork, and the same is true of many of his other pieces in the show.

However, the museumization of public art presents us with a very different experience from the one we have when we see Vega’s murals in our transit through the city. First, it opens up the possibility of pairing the mosaics with works on paper and memorabilia that help delve deeper into the artist’s creative process. Second, due to its controlled environment, the artist can manufacture the ambiance by selecting the music playing in the room and the colors that divide each of the three sections. Nonetheless, it is essential to remember that this artwork was made possible and is initially an “out in the streets”public showing, arguably because classist dynamics have historically marked museum spaces. This means that the logic of public art is subverted by exhibiting it in a museum, which makes museographic elements and curatorial decisions particularly impactful. Carefully selected elements, such as unpainted wooden walls, music, bilingual panels, and works that bring familiar faces, places, and situations, have made it a welcoming exhibition. The artist and curatorial team threw a bembé at the museum so that ostracized people from similar institutions felt like they belonged here in Byzantine Bembé.

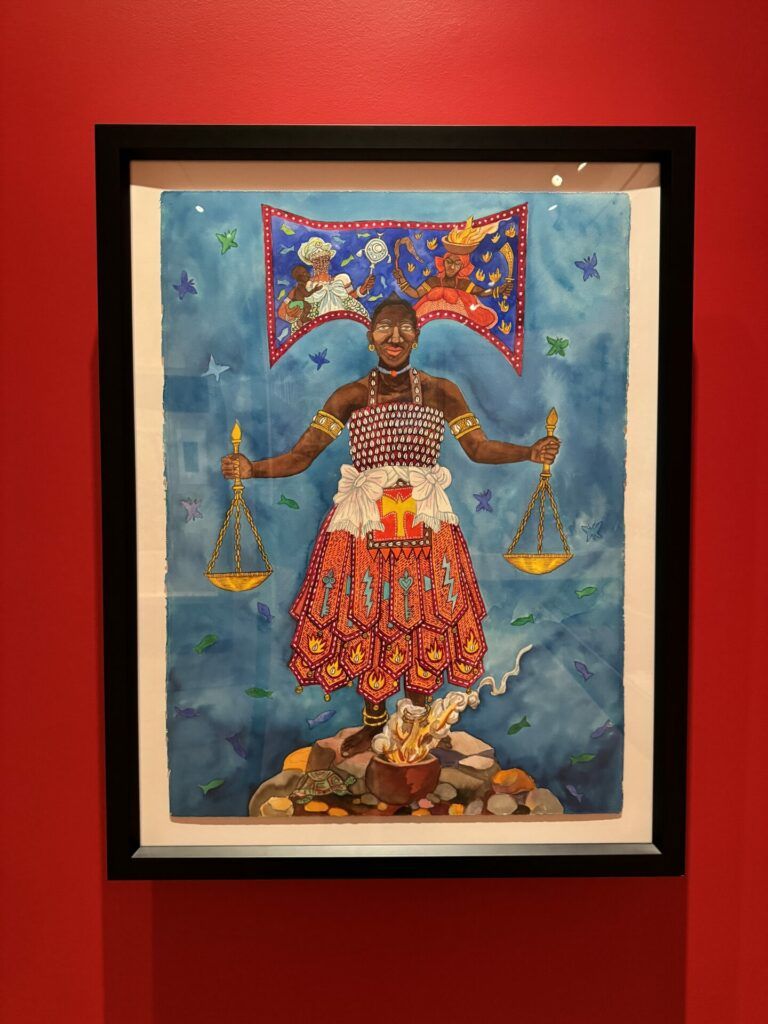

Vega devotes an entire section of the exhibition to the figure of Changó, one of the Orishas of the Yoruba pantheon, shared by several religions originating from the West African diasporas in the Caribbean and the rest of the Americas. However, unlike the Byzantine powers, Vega’s intention is not proselytizing. Based on Brazilian Candomblé, his spiritual cosmovision is rooted in physical experience, so he expresses his faith in everyday acts. This last thing is why the section in which the exhibition’s spiritual element is most present is entitled “Justicia.” He explains that he expresses this spiritual dimension precisely through the respect he gives to others. However, because of Changó’s canonical relationship with strength and struggle, the context in which Vega presents him clearly conveys resistance and the pursuit of social justice. After all, to assert respect for all in an equitable environment, it is necessary to defend the dignity of all people.

Including works produced since the 90s, this section entails a continuous struggle for justice that, presented in the current political climate, adds another layer to their reading. As Neo-Nazis march in the streets of the United States and the threat of mass deportations seems imminent, while there is an ongoing genocide of the Palestinian People at the hands of the State of Israel, funded by the U.S. and European Powers, justice requires displays of force against those who currently seek to subjugate and even exterminate complete groups of people. The figure of Changó encompasses all these issues and more.

Though his experience is rooted in the Boricua tradition, Manny Vega’s work transcends the specificity of Puerto Ricans in New York. With mastery, the artist weaves his “Figuras,” like the violence in the sport of the Puerto Rican boxer Macho Camacho, with the struggle for justice allegorized in Changó, which in turn is related to the drums, from Bomba to Salsa. These concepts reflect diverse immigrant communities in the United States, each with its own culture. Thus, the preposition “by” in the exhibition’s title entails an account of New York from the very personal perspective of Manny Vega, yet one which he has turned into a historical narrative involving the heterogeneity of the diasporas: an East-Harlem–Diasporic–Renaissance.

Consulted sources:

Brooks, Sarah. “Byzantium (ca. 330–1453)” in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (Metropolitan Museum of Art at metmuseum.org), October 2001 (Revised in October 2009). Consulted on April 8, 2024. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/byza/hd_byza.htm

López, Monxo (curator). “Byzantine Bembé: New York by Many Vega” in Exhibitions (Museum of the City of New York at mcny.org), December 2023. Consulted on April 8, 2024. https://www.mcny.org/exhibition/manny-vega

Stewart, Alison. “Manny Vega’s Stunning New York Mosaic” in All of it with Alison Stewart (Listen Notes), December 15, 2023. Consulted on April 8, 2024. https://www.listennotes.com/podcasts/all-of-it/manny-vegas-stunning-new-fq8e0kFwAE1/#google_vignette