If one was to enter the Caribbean history wing at a museum, assuming said museum would even have taken the time and space to dedicate to the subject, you would likely be hard pressed to find implements of war or defense. Fragments of our Taino past endure through fragmented ritual implements and zemi statues. This typical curation implies the biased narrative of a pious, docile culture that, when faced with the invasion of European colonists, seemed to just stop existing. Unable or unwilling to stand up to the implied might of the colonizer. Such framings create a reverberation through history in both directions. The changes reverberate through the past, erasing or obscuring the lived realities of millions. Simultaneously tearing through potential futures, attempting to use the revisions as precedent to delegitimize the struggles, academics, and communities of the inheritors of Borinken and its diaspora.

It is beyond rare to see the story of the Taino, and by extension the contemporary Puerto Rican told through the lens of armed resistance rather than the lens of conquest. Especially in these Eurocentric gallery cultures that dominate the scene. Careful curation ensures a predetermined narrative is maintained for perceived legitimacy and, while the world may wish to ignore or forget the Taino were armed, artist Amaryllis R. Flowers challenges those shackles of curated history by re-arming the contemporary.

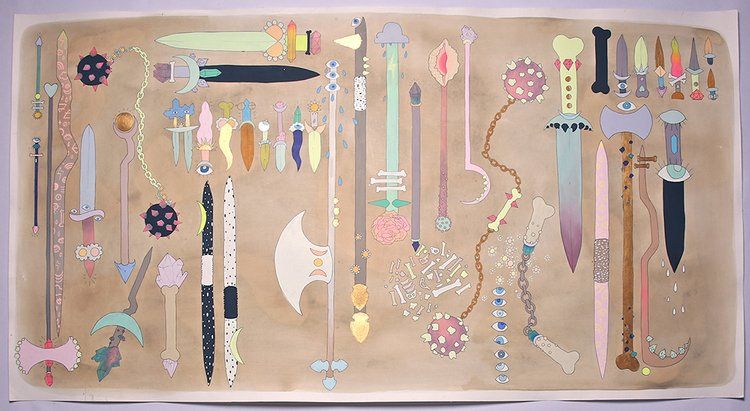

Through the creation of tools rooted in fantasy and the communal psyches desire to resist and break the historic narratives that have been ascribed to the community, Flowers interjects with unrelenting femininity and undeniable power: a power that is rooted in not only a community mindset, but the power of our Feminine and Queer ancestors who have been lost in the greater narratives of history; a loss which one could trace through the suffocating culture of Western patriarchy and machismo the Spanish interjected into the Archipelago.

In Flowers’ artist statement she invokes the idea in which “Our ancestors are unnamed and die young. In the written account of the world, we’ve hardly existed—and yet here we are.” Simply put, there is no way of knowing what was lost, the potential of centuries of narratives unprotected and snuffed out prematurely. For the Colonizer, fantasy is a luxury, an exercise in what-ifs that bear no weight in reality. Yet for the Colonized, fantasy is a necessity. Imagination is a tool of survival, a needed implement, both weapon and defense. Without it stolen memories and snuffed histories would ruin us, consume us with the inability to speculate on a time before the realities of being part of the history of the longest colonial rule in the world. Without fantasy, without speculation and the desire to fill in our patchworked histories with thoughts of worlds we can never truly know, our culture, traditions and futures would wither and fade just as colonialism intended.

Looking back through the lens of eurocentrism, a researcher would readily call Taino tales of zemi and creation a series of myths or fantasies. That same researcher would be likely to declare the traditions which shoot off from European religions, such as the Catholically rooted Vejigante, as a form of religious proceedings. In these academic linguistic conventions there is a bias ingrained which acts as a weapon in defense of the eurocentric, the familiar, the colonial. It keeps an approved perspective defended and legitimized while actively trying to unarm the contemporary descendants.

One must approach the nebulous past with the mindset of “what may have been if there had been implements of protection?” A mindset readily presenting itself in works such as “Protective Shield Made from the Remains of 1,000 Warriors,” a 2018 sculpture comprised of a collection of disembodied acrylic nails and faux hair. To frame this as an implement of defense made from a distinctly feminine ornamental material positions generations of queer and feminine Puerto Ricans as bastions of survival and cultural importance that historical narratives have often excluded them from. To have the user take shelter behind the shield that is symbolically made of the remnants of 1000 acrylic wearing warriors frames its defense not as an act of cowardice or diminishing oneself, which is often seen or implied in Eurocentric depictions of hiding oneself behind a shield, but rather an act of communal care or sacrifice. One that ensures the user can continue on with the blessing of those who came before. This work and others Flowers produces are masterclass in what some may call speculative fiction or historic fantasy while simultaneously rooted in the contemporary conversation surrounding increased violence and aggression in both the social and political climate surrounding the same queer communities Flowers works strive to arm and protect.

the-dark paint, wood, glitter, braiding hair, vertebrae. Image courtesy of the artist.

You see this essence of ancestral power in other works by Flowers, such as entries from the Apothecary(Tools) series in which an illustrative manuscript serves as the blueprint for several real life fabrications. Two of these fabrications, a handaxe and a dagger, both feature bone fragments or motifs. Further exploring the idea of having ancestral protection as you take up arms. While the handaxes bone source is ambiguous, the dagger clearly features the jawbone of a Deer. This imagery invokes echoes of other indigenous cultures from far corners of the world which consider the deer to be a divine messenger as well as invoking the prominent use of animal parts in fantasy design. Something that Flowers uses to “unbind us from trauma” as per her own artist statement.

Even in works like “The Healer”, a chained morningstar, one can see Flowers’ call to arms merged with a distinctly queer and colorful sensibility that urges the user of the tool to protect their energy. On this weapon are painted two hamsa, a feminine hand symbol which wards off the mal de Ojo or evil eye by acting as a barrier, much like in the “Protective Shield Made from the Remains of 1,000 Warriors”. Both works invoke femininity to act as a protector to the user, and in both cases these symbols, whether it be literally in the Shield, or metaphorically in the case of the Healer, invoke the protection of others. With the healer being an implement of violence named ironically opposite to its form. It asks a critical question, what value is violence to the process of healing? At what point, if at all, could it be necessary to the healing of a long embattled and abused community to fight back with force, rather than hunker down and become lessons in resilience. When does the community get its chance to fight for themselves rather than endure? One is reminded in a roundabout way of those contemporary museum narratives and the western value placed on driving the narrative of nobility and passivity of any of their victims existing outside of the predetermined social hierarchy. One which spreads outwards to strangle resistance at every level like a fantastical beast.

Flowers’ work highlights the value of reliance on community and honors the feminine and the queer while never shying away from the task at hand: the unshackling of the Puerto Rican people from conventions and historical abuses of western history and the metaphorical monster they have created to defend it. As Flowers said best in her own artist statement:

The core of my art making practice is storytelling. I make large-scale images of psychic rebellion and objects which reconceptualize Divine power as ungodly and hyper feminized. I tell fantasies of survival for those of us not meant to outlive the hydra of American imagination.

– Amaryllis R. Flowers

Through her explorations of tools and fantasy Flowers deftly asks the viewer to engage with liberation using the medium of fantasy to entice the hesitant and empower the willing to embrace these radical assertions as a new gospel. To take pleasure in things that generations before have been taught to be ashamed of. Arming the community with words, ideas and even weapons to empower a new generation which feels supported and empowered to advocate, fight for and design a new contemporary Puerto Rican culture. One that appreciates the machinations of the past while refusing to be shackled to its more negative trappings any longer. The viewer must remember Flowers is a self described storyteller, and they must be willing to acknowledge their place in the narrative. The viewer must recognize themselves as a stakeholder in the future of their community and actively choose to offer the implements of defence and empowerment Flowers presents them with to carve out a new cultural gospel of radical inclusion.

Flowers is one of a growing coalition of Boricua Artists and Storytellers who are carving out a long overdue and long deserved space in the contemporary conversation. With continued highlights and community support, creators like Flowers are positioned to be recorded as members of a New Diasporic Renaissance in Caribbean art and culture, a renaissance in the contemporary political climate with yet unforeseen, and desperately important cultural impact.

References

- Flowers, Amaryillis. “Artist Statement.” Amaryllis Flowers . Accessed October 21, 2024. https://amaryllisrflowers.com/artist-statement.