Amanda Carmona Bosch is a rara avis in the history of Puerto Rican art. In her work, her language, her relationships, and in her life trajectory, self-determination has been the compass guiding her path. Resistant to models and defiant in the face of conventions, this artist from Río Piedras has developed her life and career against the current, embracing isolation, if that was the price she had to pay for freedom—artistic or personal.

It was in 2006 that her work first crossed my path, during the curatorial research for an exhibition in which her work stood out prominently. After that shared experience in Mayagüez, nearly twenty years ago, our paths met again, in the development of a series of retrospective exhibitions reflecting on the major themes within her work. The first exhibition was on war, titled El mal (Evil), and held at La Liga de Arte de San Juan between January and March 2025. The second opening at the Museo de Las Américas in 2026 will center women and their bodies. Migration, nature, and visual thought will shape the remaining exhibitions. As these take shape, the following lines translate the conversations born from our mutual understanding.

In Transit

Laura Bravo López: Your life has unfolded in constant transit. From a very young age, you set out far from Puerto Rico, but it’s striking that your destination was not New York, a city that has drawn countless artists from the 1950s to the present. You have lived in Mexico, the Dominican Republic, Spain, Austria, the United States, among other places. Over the past eight years, your residence has shifted, like a pendulum, between two cities: San Juan and Vienna. This process is not trivial. It takes place between two different continents, two cities with distinct idiosyncrasies, customs, languages, artistic contexts, circuits, and markets. This inevitably shapes a different perception of your surroundings, which permeates your work.

Amanda Carmona Bosch: It was never my plan to live so long outside of Puerto Rico, but that’s how it happened. Even before adolescence, while flipping through art history books, I resolved to explore the world. I left Puerto Rico at twenty, right after finishing my bachelor’s degree. I had already traveled through Europe as a student and visited New York. In the 1970s, it struck me as an inhuman place. In fact, I even turned down Pratt Institute, where I had been accepted for a master’s in fine arts program. You could live more meaningfully in Europe—and on half the budget. I first went to Italy, where no one was expecting me, and then to a small village in the Austrian Alps, where no one could understand me. I liked the challenge. I think I was seeking silence, for a way to survive without distractions. I lived a spartan life, dedicated to painting and exploring new ways of thinking. This constant change—starting over again and again—teaches you quickly how to live, and how to die. Everything is a paradox.

LBL: How does this constant coming and going reflect in your artistic production, in your way of understanding and recreating the world?

ACB: Early in my career, living in Austria influenced my decision to adopt abstraction and shaped the way I think visually. It was a moment when technical and existential maturity coincided with the chance encounter of a group of abstract artists. Abstraction was no longer just in the books I read. I was familiar with the work of Julio Rosado del Valle, of course. However, I had no mentors in Puerto Rico, no models in professors or artists who practiced or spoke passionately about abstraction. That said, very few of my works are obvious or direct reflections of my life experiences in other geographies. Most of my work stems from a need to express life as an act of survival, of resistance. Perhaps literature was the deepest source of that creativity —books on nearly any subject, slow reading, and the isolation I have always lived in.

LBL: These past eight years your residence alternates between Vienna and San Juan, beginning after the impact of Hurricane María in Puerto Rico in 2017. At the time, you were in Austria. How did that experience shape this stage of maturity in your life?

ACB: In the terrible weeks following the hurricane, I had great difficulty returning to Puerto Rico. That time, not going back was out of my control—if I ever had control over my fate. I only go to Vienna because my only son and grandson live there. My age no longer matters. I’m still struck by the contrast between one world and the other, so much that I have to adapt again and again to cultures that do not intersect, almost opposites in everything, starting with their attitude toward life.

Being a Woman

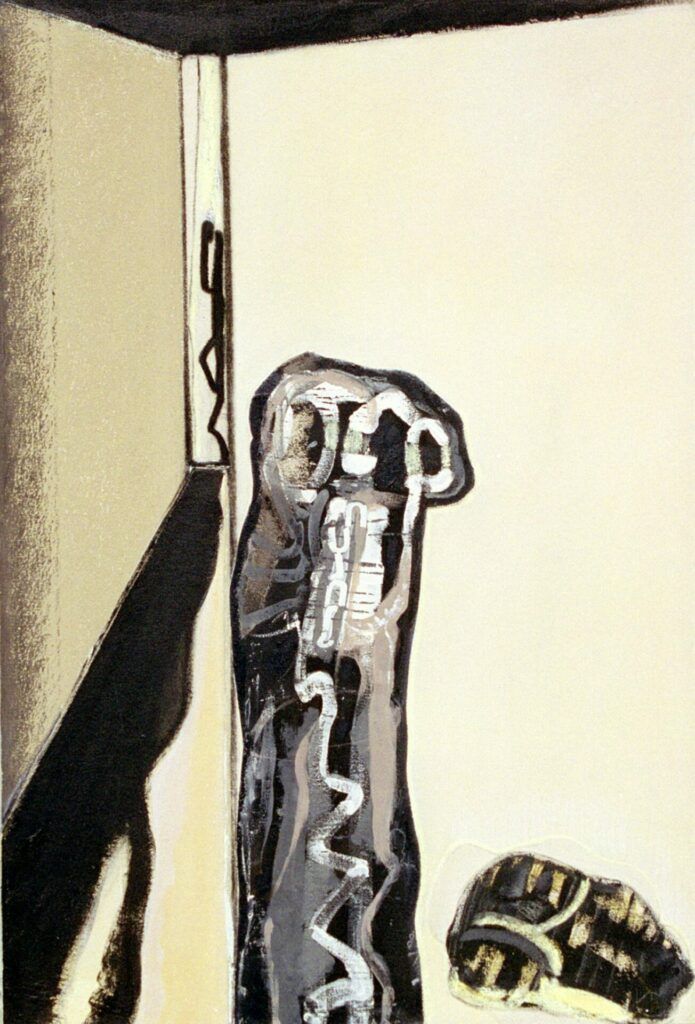

LBL: One of the main focuses of the retrospective exhibitions you are preparing centers on the body. As a woman who has given birth to a child and who has also experienced illness, you understand that the skin and organs we inhabit are in constant transformation. They define us, limit us, and shape our very existence. What aspects of these physical experiences are reflected in your work?

ACB: Being born in a woman’s body determines much of your life, whether you have children or not. It’s not just the biological part, which can be managed—even if you get breast cancer, as I did. The problem is cultural—it crushes you as a human being. Being a rebellious woman in a macho culture, an unconventional mother, and trying to be an artist outside the established circuit? Tough, but that’s how it was. My experience of the gestating body, of pregnancy, has been significant in my work. I have continuously explored the mother-child relationship as an indestructible symbiosis, but I also have addressed abortion, menstruation, childbirth. In the end, a body from which another body emerges is the most striking thing for a girl who learns what it means to be a girl. As an image, it’s priceless.

Visual Thought

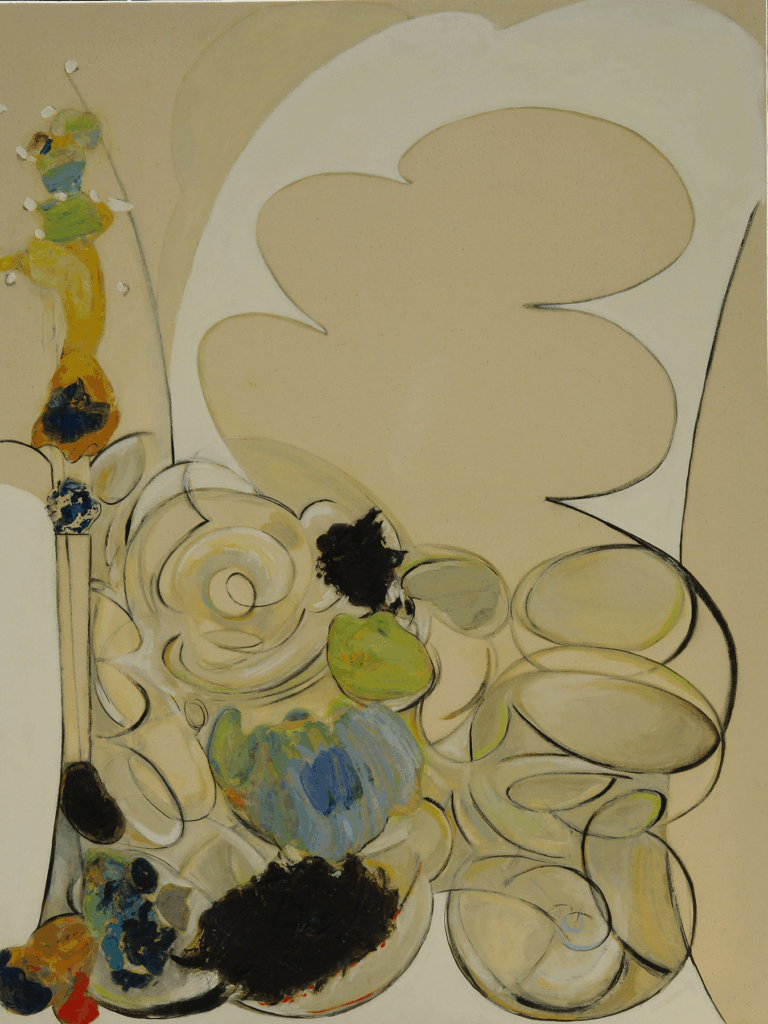

LBL: In representing these issues, you break with a long figurative tradition and lean toward abstraction, a language that has been a backbone of your career. However, your work shifts between abstraction and figuration. How do you manage this constant push and pull in your art practice?

ACB: That push and pull is real—it’s exactly like that. When I create, sometimes I start with a theme, other times I scribble and later realize what I’ve done. I interpret it. Either way, it’s an interpretation of the appearance of things.

LBL: That reminds me of the automatism promoted by surrealism.

ACB: Exactly. I try to feel what lies beneath physical appearance or, simply, I think about ideas, emotions, sensations, or concepts that are themselves abstract. You can always give them some kind of shape. For example, the series I created around philosophy tries to do just that—deliberately illustrate an abstract idea or concept. The series called Visual Thought, on the other hand, is pure automatic drawing.

LBL: So, haven’t you had interlocutors in this visual practice?

ACB: Seeking them out was not my concern. I wasn’t interested in the movements or trends “of the time I happened to live in.” I tore apart that idea. Abstract art has existed for thousands of years. I only paid attention to how something was done—the techniques. Another problem abstraction brought me is that, back then in Puerto Rico, few people dared to speak or write about abstract art, especially if they couldn’t find equivalent models in art history books to match what they saw in studios or exhibitions.

Nature

LBL: During your six-month stay in Puerto Rico every year, you spend part of your time in Maricao. This setting of lush, dense nature is highly relevant for part of your artwork. Nature surrounds you but also shapes your way of understanding life, its transformations, its parallels with the human body and life cycles. Likewise, nature’s destructive power dramatically affects our lives in the Caribbean. How is this awareness represented in your work?

ACB: Indeed, our natural environment has been present in my work over the years. For example, I created the Hurricane series (a quintessential tropical subject) in Austria, in 1979. I painted that, even decades before María, because a botanist friend once told me that hurricanes are good for nature’s regeneration, and that struck me as something wonderful, in a philosophical sense. Today, it’s a tragedy—because of us! I have spent periods of my life in rural areas: as a child in Comerío, later in a small town in the Alps, and in Samaná (Dominican Republic), from 2004 to 2010. In any case, my love for nature, especially botany, is linked to motherhood, to the miracle of evolution, in contradictory terms (laughs). I paint out of love or pain. That’s life, isn’t it?

LBL: In that sense, it’s like bringing to light that the seed of art springs from the depths of the artist’s being.

ACB: That’s right. The two things that have always captivated me the most, visually and existentially, are nature and art. I never knew whether I preferred a tropical jungle or a good museum. That question set me on a path toward two very different lives. I chose art—for better or worse.

LBL: But are they incompatible?

ACB: Yes. Art is a matter of the city, mainly due to issues of dissemination.

Creation and Freedom

LBL: The artistic contributions of many women have gone unrecognized for centuries, especially when judged by the standards of the art market, and Puerto Rico has been no exception. Do you feel your work has been held to a different standard than others from your generation?

ACB: My generation has brilliant artists of all sexes and genders, and we share meaningful connections. The cultural industry is something else. The art world has always been an elitist and self-centered space. If you’re not part of privileged circles in one way or another, you’re left to navigate the expectations imposed by the cultural power structures of your time. I was an absence, and a strange one, because I didn’t choose to emigrate to the metropolis. I had no mentors and was flatly rejected. I wasn’t sociable either—rather withdrawn, distant from the scene. Self-promotion (a contemporary imperative) is something I’ve only begun to do now, in my own terms, at sixty-eight. It’s quite exhausting, by the way, a tremendous distraction from creative work. In my time, few women artists had the backing of family, partners, or those who held power over the systems of validation, promotion, and sales of art. Social stereotypes placed an aura of admiration on men. Have things changed? The market and cultural institutions—now harmfully intertwined—only needed to include a few women, that’s all. In short, it’s a complex issue, and I have paid the price. I don’t even appear in a pamphlet about the history of Puerto Rican art. It was painful, as it made my life harder, but it never discouraged me from creating the art I wanted, and I was much better off for it. That wonderful freedom comes at a price.

This text was written, hand in hand, in Puerto Rico and Austria, between April and May of 2025.