Bibiana Suárez, born and raised in Puerto Rico and now based in windy city Chicago, blows the Caribbean wind through her work. Her exhibition “In Search of an Island” was shown at Sazama Gallery in Chicago in 1991 but I connected strongly with it seeing it for the first time from Bayamón, Puerto Rico in 2024.

This exhibition feels like both a foreshadowing (of Hurricane María) and a documentation of history (hurricanes like 1989’s Hugo). The work feels urgent and current and part of the body of climate change art. The documentation of climate change through artistic expression is important to our collective memory, and through her work you see how linked Puerto Rico and hurricanes are. For me, she captures the feeling of passing a hurricane in Puerto Rico precisely.

In her piece “Juracán” we see a wind swirling around a skinny mountain crag. The emotion of the piece is vulnerable and teetering on a precipice. The wind around the peak is an opaque grayish blue and it surrounds and isolates the mountain. Juracán, a Taíno word, was a name for the god of chaos and destruction who caused wind storms when displeased.

For me, the gray of the piece is the gray of no sun. Venturing out of the apartment after Hurricane María, we did not know what time it was, there was no sun in the sky to tell us. We knew the night had passed and it felt like morning but wasn’t, it was close to 4pm. The gray of the sky mirrors the darkness of the power getting knocked out. I write this in the aftermath of another general blackout, New Year’s Eve, 2024. The pointed thinness of the mountain peak is like the antennas you see blinking in the mountains of Puerto Rico. Even in the flatter city, the mountains are almost always in view, reminding you of the vastness of the island. Near where I live, more than once someone has driven up the private road looking to access the highest viewpoint, the antenna.

The colorlessness of this piece foreshadows the days, weeks, and months of darkness that come after a hurricane, the weeks of no power after María, the hopelessness of knowing that today the light will not come back.

In the piece “Huracán Centella (Study)” she uses this old fashioned word “centella” which means a spark or a flash of lightning. She also has changed to using the Spanish spelling of the word hurricane (still not using English!), a contrast to her earlier usage of the Taíno word, a commentary on the colonization of language, the passage of time, and the history of Puerto Rico. We can feel the power of this painting and it’s scary. We see the wind whipping and can hear the all-enveloping noise. One of my strong memories from the night of María is how loud it was outside, we could hear things slamming into each other and things breaking apart. In the art we see the sea and the sky connecting and it’s hard to tell if the hurricane tunnel swirl is over land or water. The painting technique she used here to give it so much movement is remarkable, and it gives me a racing feeling.

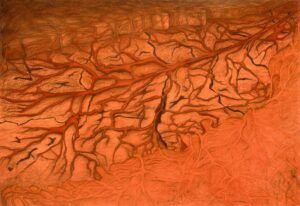

In her pastel on paper “Uprooted,” we see the shape of the island carved out in negative space, dug out like a canyon. There are roots extending across the island’s border, connecting to the ocean and the rest of el Caribe. She draws the hollowed out three dimensionality of the island with the roots left behind intact. This could be speaking to the migration of the majority of Puerto Ricans from Puerto Rico to the United States. The people who have moved for educational or job opportunities or to escape the aftermath of a hurricane. The population living in Puerto Rico these days skews older, more deeply rooted for more time, in the land.

A thick main root surges through the center of the island from West to East, almost in line with the Ruta Panorámica, and the perimeter of the land mass is not fully on the page, the Western border invisible. We can’t see the limits of Puerto Rico, which makes it feel big and diasporic. Uprooted is a verb that signifies an imbalance of power, someone/something has been taken away from their roots, being pulled up and out of their culture. Many US born Boricuas don’t necessarily ever learn Puerto Rican Spanish, a unique language spoken in the archipelago.

Uprooted is how the island looks after a hurricane as well, trees uprooted, electrical posts pulled out of the ground. Uprooted also makes me think of root vegetables, viandas, an abundant source of sustenance in PR, that grow everywhere. The gentrification that is happening in Puerto Rico, as people are uprooted from their homes or businesses by an Airbnb or gringo-run art gallery makes me think of this painting.

Uprooting something is taking action upon it, the thing being uprooted has no agency. It’s the opposite of being grounded and at home. The reddish-orange color reminds me of clay and unlike other works, hot colors are used here.

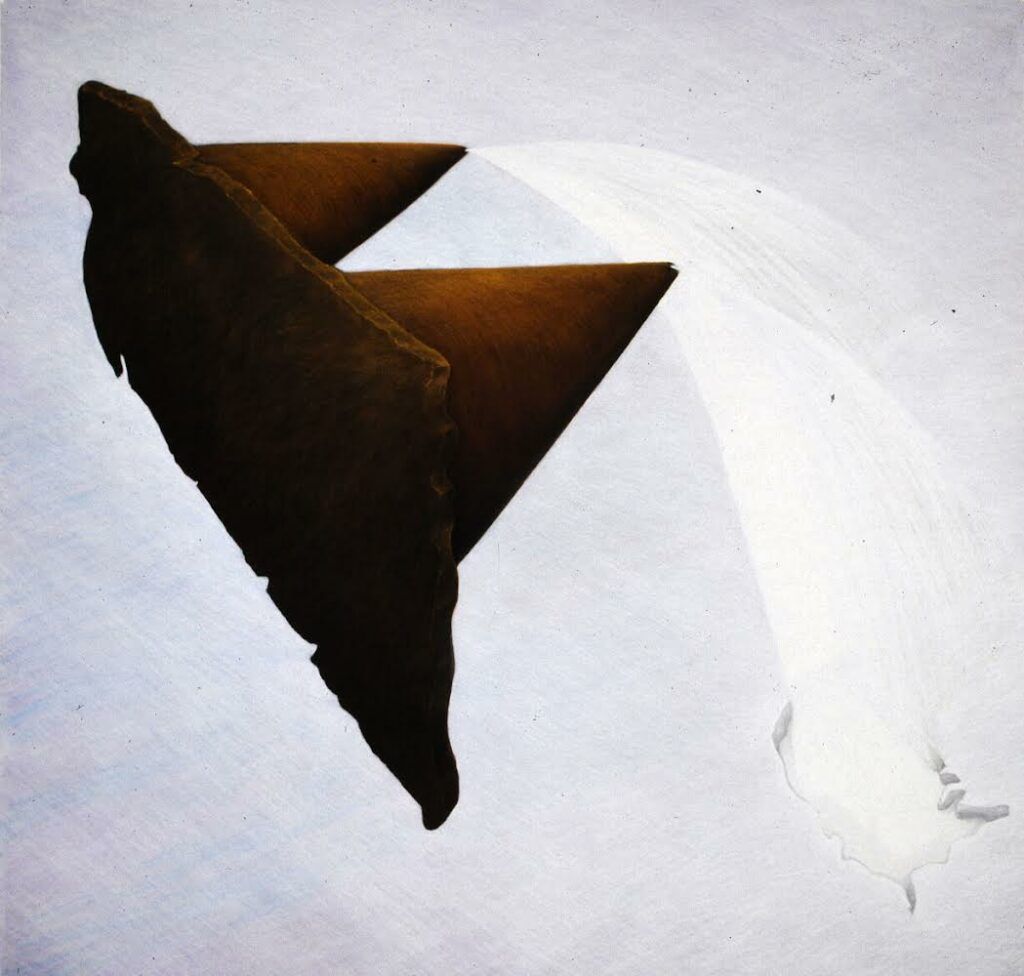

“Isla Madre/Isla Negra” features a big Puerto Rico dark in the foreground with streams of water shooting out of two mountains or breasts (reminiscent of Cerro Las Tetas or Las Tetas de Cayey). Half of the name of the piece, Isla Madre, posits the land as feminine. At first look, I interpreted the piece as water raining down on the empty outline of the USA below. There is a stark color contrast in this one, Puerto Rico and its mountains dark against a bright white background and the white United States. The white color could be the white washing of culture when people move to the United States. The other half of the title, Isla Negra, roots Puerto Rico in its African and Black heritage.

The island is flying and birdlike, which harkens to Puerto Rico’s and Cuba’s characterization of being two wings of a bird. The piece positions Puerto Rico in the sky above the US, the streams cascading down, perhaps representing the stream of consciousness, the fate of Puerto Rico linked to its status with the US, always there but far away, and transmuted across water. The United States below looks like an empty tray ready to feed off the island. Act 60 and Ley 22 are just recent examples of how the US feeds off of Puerto Rico, parasitic apartheid practices that allow gringos to move to Puerto Rico, become residents, and enjoy tax breaks only available to them.

The flow could also be a leak, Puerto Rico leaking population and brain drain to the United States. Instead of how we often see Puerto Rico on a map, below the United States and relatively small, here we see the island huge and above, the roles reversed, and Puerto Rico is giving to the United States in this image, and gaining nothing in return.

Upon revisiting the work, I see the tetas are actually coming out of the back of the island, which could be Puerto Rico turning its back on the United States, showing that the island thrives and grows strong without the colonizer.

The name “Isla Madre” also conjures Puerto Rico as a place that had female leadership earlier than the United States, from Felisa Rincón de Gautier, the first woman to be elected mayor of a capital city in the Americas (elected 1947) to Sila María Calderón Serra, first female governor elected in 2001. While the Isla Madre has been progressive in female leadership, it is and has been in a state of emergency for femicide and gender-based violence: the two streams of water, a mother weeping.

The mountains on the island could represent the two tiers of the title, and could be arms outstretched, or weapons, guns. The island has freedom of movement while it remains feeding and watering the colonial power.

In “Erizo (Sea Urchin)” we see a small erizo with shadows of palm trees blowing over it, covering and protecting it. The sandy yellows of the pastels suggest we might be looking at the erizo through water, near the shore on a sunny day with the shade of the palms above. The erizo is at home and stable, unmoving as the palms blow in the wind, surrounding her in shadows. The wind here is tangible, and though it is not a hurricane wind, we still feel the breeze. We can see the golden sand and feel the sunshine here. The shadows look like fish swimming and the erizo is holding on tightly while everything else, the trees, water, wind, is moving and blowing. I love the contrast of the stiff spikes with the undulating water and trees.

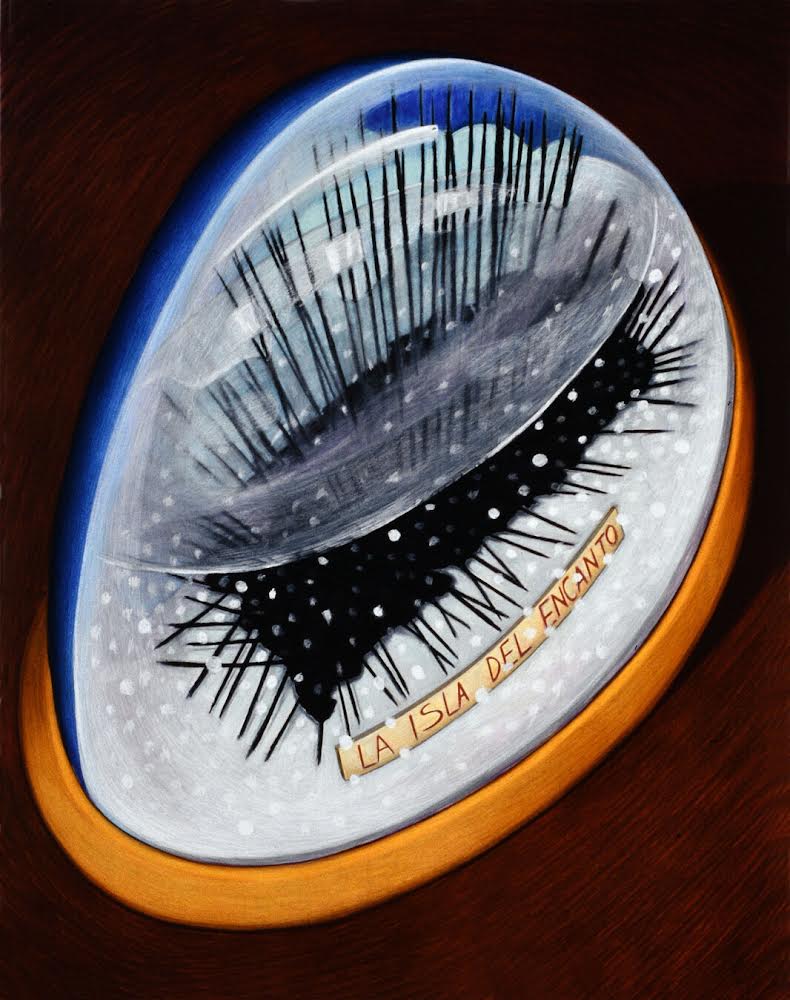

“Isla Del Encanto” is a piece I see as a commentary on tourism. A tourist has bought the trapped and spiny snow globe erizo and it is underwater getting snowed on with its spikes sticking out. Outside of the snow globe we are in an interior space, we see the globe and the island as a collectible.

I love this piece because one of the things I hear tourists complain about walking from the beach to their rental car is spiny ocean thorns getting stuck in their feet, an allegory for the United States’ presence in PR, colonizing a place and then complaining about it. The snow falling over it is a juxtaposition of the cold versus the erizo’s natural environment of warm tropical weather. Snow, cold and ice are things students on the island learn about and associate with winter and Christmas, (check the many inflatable snowmen that are set up at the start of Christmas season), though snow never falls here. Chicago however, is freezing in the winter, and perhaps this work is a personal allegory about Suarez’s move from Puerto Rico to the North of the United States.

In the snow globe, the enchanted island is underwater and cold. But while trapped, the erizo protects itself, and we wouldn’t want to touch it. This could be a reference to Puerto Rico’s status, in limbo but captured, not able to change its status to statehood nor independence, but encased and labeled, a scientific specimen to be studied and stored.

Inside the snow globe we see tentacles reaching out, but the erizo looks dried up or frozen. Maybe it is dead. The back copper edge of the snow globe is in shadow and the point of view is looking down and towering over the souvenir. The spines on the sea urchin remind me of cables, electrical poles and wiring, an inescapable feature of the city- and countryscapes of Puerto Rico. A mess of wires that don’t work. The erizo has been captured and tagged, losing its enchantment.

Overall, the movement in Suarez’s work is so palpable you can feel the elements: wind, water, earth, and sky. The shading and lighting she uses in her pieces is remarkable, at times warm and then freezing cold. I feel a sense of grief looking at her art, grief from the devastation of hurricanes and colonialism, but I also feel a sense of great power and healing. Puerto Rico will continue to protect herself as the wind keeps blowing.